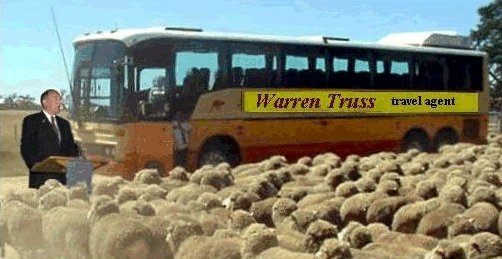

2004/02: Should Australia cease exporting live sheep and cattle?

... and don't forget, my friends, your retirement trip includes free accommodation, medical care and food. And I assure you that you'll be delighted by the legendary lands of Arabia. Why, you may never come back! |