Search for listed newspaper items online - see end of this page

Search for listed newspaper items online - see end of this page

Search for listed newspaper items online - see end of this page

Search for listed newspaper items online - see end of this page

|

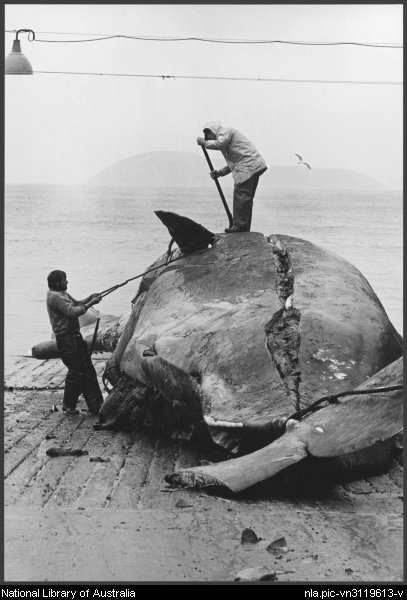

The ABC's Catalyst program recently presented a 12-minute segment on scientific whaling. In this segment, a panel of experts goes through all known research documents arising from Japanese whaling. A direct link to the Web version of this program can be found at http://www.abc.net.au/science/broadband/catalyst/asx/whalescience_hi.asx Caution: you will need a fairly fast connection speed to view this film - broadband preferably

The ABC's Catalyst program recently presented a 12-minute segment on scientific whaling. In this segment, a panel of experts goes through all known research documents arising from Japanese whaling. A direct link to the Web version of this program can be found at http://www.abc.net.au/science/broadband/catalyst/asx/whalescience_hi.asx Caution: you will need a fairly fast connection speed to view this film - broadband preferably