Related issue outlines: 1997: Censorship: should the viewing public have access to violent and sexually explicit material? Dictionary: Double-click on any word in the text to bring up a dictionary definition of that word in a new window (IE only). Analysing the language of the news media: Click here to read a useful document on media language analysis For later or follow-up newspaper items (additional to the items displayed in the newspaper items section at the end of this outline) , go back to the Newspaper Index section of the Echo site. Use the search-words violent and video |

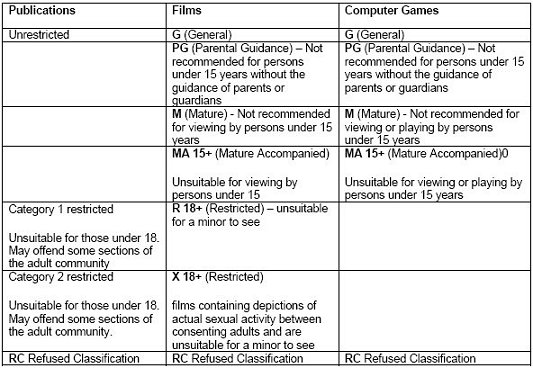

Commonwealth Legislation

Commonwealth Legislation