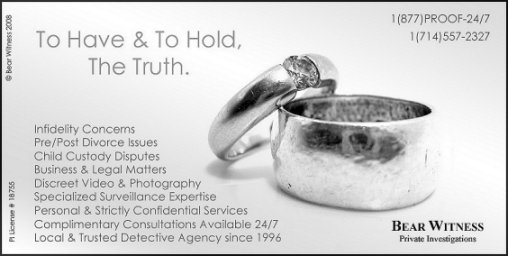

Right: Prior to Australia moving to "no-fault" divorce, private detective agencies flourished on work generated by divorcing couples. "Private Eyes" placed advertisements in newspapers, similar to this ad which recently appeared in an American magazine.

.

Right: Prior to Australia moving to "no-fault" divorce, private detective agencies flourished on work generated by divorcing couples. "Private Eyes" placed advertisements in newspapers, similar to this ad which recently appeared in an American magazine.

.

Arguments in favour of retaining 'no-fault' divorce

1. Divorces are likely to be more acrimonious or unpleasant if fault provisions are re-introduced

It has been claimed that fault-based divorce tends to be far less pleasant than no-fault divorce. Establishing grounds for divorce often involved the hiring of private detectives to prove grounds such as adultery. Sometimes one or more of the partners in the divorce created false grounds to justify a divorce.

In an article published in The Sydney Morning Herald on July 18, 2009, Rick Feneley and Stephanie Peatling noted, 'This week private investigators recalled the dark old days of gathering the required damning evidence, when they would crash into motel rooms in a blaze of flashbulbs to catch adulterers in the act; when a husband would hire a prostitute to pose as his lover, so desperate was he to escape an unhappy marriage; when couples, agreeing they wanted to part, would resort to such fraud to persuade the Divorce Court; when newspapers would publish all the grubby detail, no names withheld.

Women's advocates see no advantage in a fault-based system. Elspeth McInnes, from the National Council for Single Mothers and their Children, says it could only achieve the return of 'protracted, bitter proceedings at immense cost and with crippling complexity'.

Alastair Nicholson, the former chief justice of the Family Court, was a lawyer in the days of fault-based divorce, and he found the system "degrading and unpleasant". He believes it would be dangerous for judges to get back into the business of apportioning guilt in matters of the heart. And he says governments have no business prolonging bad marriages.

2. Fault-based divorce is likely to make amicable child-custody arrangements more difficult to achieve

It has been claimed that returning to fault-based divorce would exacerbate ill-feeling between the divorcing parties and that this would make it harder for divorced parents to reach workable agreements on how to care for their children.

Australian National University family researcher Professor Bruce Smyth has claimed that those who would pay the highest price if fault were returned to divorce laws would be the children of separated parents.

Professor Smyth has stated, 'The social science evidence is clear: children do best when parents get along. Why was fault taken out in 1975? Back then, it was well known that when you have a barrage of affidavit materials making character assassinations on the other parent, it would do very little to build co-operative parenting relationships.'

Divorce is likely to have damaging effects on children. David H. Demo and Andrew J. Supple in their article on the effects of divorce on children noted, 'Marriages that end in divorce typically begin a process of unraveling, estrangement, or emotional separation years before the actual legal divorce is obtained.

During the course of the marriage, one or both of the marital partners begins to feel alienated from the other. Conflicts with each other and with the children intensify, become more frequent, and often go unresolved.

Feelings of bitterness, helplessness, and anger escalate as the spouses weigh the costs and benefits of continuing the marriage versus separating.'

It has been claimed that if the divorce can be achieved legally through a no-fault process then some of the antagonism can be reduced and that this is of benefit to the children involved who will witness less hostility and will be less likely to be required to take sides in the conflict.

It has further been argued that custody arrangements are likely to be more amicably achieved if the divorce has been achieved through a no-fault process.

3. No fault divorce makes it easier for children to keep a positive relationship with each parent

Referring to the United States where fault-based divorce still applies in some states, a number of social commentators have noted that fault-based divorce is likely to damage the children's relationship with their parents.

Inn 2002 Barbara Dafoe Whitehead noted, 'Requiring fault would be bound to hurt the children who will be caught in the crossfire. If we have learned anything from thirty years of high divorce, it is this: When divorcing parents have legal incentives to fight, they will. And fault gives them yet another incentive. Inevitably, children will be recruited as informants and witnesses in the legal battle to establish fault. The fault finding may also be exploited to prejudice or interfere with the child's attachment to the "at-fault" parent. Of course, this ugly practice of blaming and discrediting the other parent goes on under no-fault divorce law, but fault will provide legal justification for such behavior.'

4. Fault-based divorce could keep partners together in unhappy marriages

It is claimed that a full return to fault-based divorce could see many couples remain in unhappy marriages because they had insufficient grounds to legally divorce.

Critics of fault-based divorce compare the situation in the United States unfavourably with the situation in Australia. The United States has fault-based divorce in many states, where Australia does not.

In an article published in The Sydney Morning Herald on July 18, 2009, Rick Feneley and Stephanie Peatling noted, 'If New Yorkers want to leave their spouse, incompatibility is not accepted as grounds to end the marriage. Unless husband and wife agree to part, one must prove the other is to blame before a court will dissolve the union.

One of the few grounds for divorce in New York is cruel and inhuman treatment - but courts commonly set a very high bar for what qualifies, particularly when a couple has been married a long time. In Shortis v Shortis in 2000, the attempted choking of the husband and the threat to slit his throat was not cruelty. Fuld and Fuld were married for 45 years, but hadn't spoken for three years. Husband told terminally ill wife to "drop dead" and aggravated her by playing the television loudly, but this was not cruelty. In another case, throwing dishes at a husband, pulling his hair and destroying his clothing did not amount to cruelty.'

In the United States divorce is an issue of state jurisdiction, and so the introduction of no-fault divorce varies from state to state. Some states have yet to adopt any progressive reform, and so allow for comparison between states were there is no-fault divorce and where there is not.

The findings reveal that under no-fault laws a wife can threaten to leave an abusive husband, and this becomes a credible threat. Under the old regime, this was not so. It appears that the fear of divorce creates a strong incentive for abusive partners to behave.

More generally, easy access to divorce redistributes marital power from the party interested in preserving the marriage to the partner who wants out. In most instances, this resulted in an increase in marital power for women, and a decrease in power for men.

An analysis of United States data reveals no-fault divorce has caused female suicide to decline by about a fifth, domestic violence to decline by about a third, and intimate femicide - the husband's murder of his wife - to decline by about a tenth.

Australian data seems largely consistent with these findings. In the decade after the introduction of the 1975 Family Law Act, female suicide declined by roughly 20 per cent, or about 100 victims a year, when compared with the preceding decade.

5. The opt-in nature of the proposed fault-based divorce is illogical and unwieldy

There have been many critics of Mr Abbott's suggestion that couples be able to decide if their marriage can only be terminated in a fault-based manner.

It has been noted that only those couples most strongly committed to their individual union and the institution of marriage would be likely to decide, prior to getting married, that they wanted stricter provisions to apply should they ever seek to divorce. Critics conclude that these are the least likely people to finish up contemplating divorce and thus Mr Abbott's proposal is of little pointless.

This position has been put on the blog site 'Quote the Raivans', where the suggestion was made that 'If both parties share a belief in "traditional" marriage then surely their promises in the eyes of the Lord have more power than a secular legal contract. Making marriage harder to get out of only benefits those who don't want to get out of one, and probably they're not the ones who are trying to do so.'

There are also those who note that an opt-in provision would be difficult to enforce in the event that it were ever required. Couples who married in the belief that they would never divorce may be prepared to opt for harsher divorce provisions. However, should they reach a point where one or the other of them wanted to end the marriage, then they would be likely to want to sidestep the fault provisions for which they had volunteered.

In the online opinion site, 'The Social Critic', one of the commentators stated, 'The proposal does not go so far as to suggest a return to the days before the no-fault divorce laws of 1975 but [it] does suggest a commitment by couples who marry to decide on their own to make getting a divorce much harder than it is now and opt in to a fault-based divorce.

This may sound very wholesome on the surface, but without making it an actual law, it is difficult to understand how such a commitment would be binding.'

In the United States, Louisiana, Arkansas and Arizona have laws that give newlyweds - as Abbott suggests - the right to "opt in" to a fault-based system. But they have not resulted in fewer divorces, says John Wade, chairman of Australia's Family Law Council. And he says divorce courts have tended to ignore these private agreements. In any case, 97 per cent of Louisiana couples still opt for no-fault divorce.