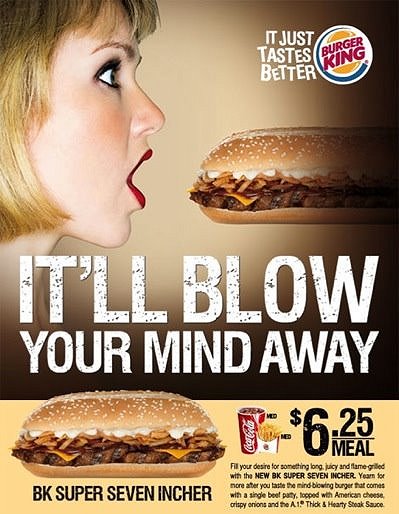

Right: A Burger King poster, this time aimed at adults, stressing the "value-for-money" in a giant hamburger

.

Right: A Burger King poster, this time aimed at adults, stressing the "value-for-money" in a giant hamburger

.Arguments against the government imposing restrictions on fast food advertising

1. The extent of the childhood obesity problem in Australia has been exaggerated.It has been claimed that Australia's childhood obesity epidemic has been exaggerated and is only increasing in lower-income families. These claims are said to be supported by recent research findings.

The findings are based on measurements taken from thousands of Australian children in 2000 and 2006 in two nationally representative samples. They found that the growth in childhood obesity overall has slowed to a crawl and the only statistically significant increases are now among boys and girls from low-income homes.

The findings are based on two studies using nationally representative samples, one conducted in 2000 and based on 4500 primary and high school children, and a further study of 6000 children in 2006.

The overall obesity rate rose only slightly from 6.0 per cent in 2000 to 6.8 per cent in 2006. Researchers said the increase was not statistically significant.

Jenny O'Dea, associate professor of child health research at the University of Sydney, stated there is 'no doubt that it (childhood obesity) has been exaggerated.'

Professor O'Dea said there had been an assumption that all of our children are at risk of obesity and ill-health. This latest data shows that's not really true - there's something protective about high income and middle income, and the real risk has been in low-income children,' Professor O'Dea said. 'They (other experts) have to look at the evidence, and they are refusing to do it.'

The head of at least one school in an affluent part of inner-eastern Sydney yesterday agreed the obesity problem was neither as ubiquitous nor as uniform as sometimes supposed. Gabrielle McAnespie, principal of St Charles's Primary School in Waverley, has stated, 'This is my 28th year in teaching, and over that period of time I can't say I have noticed an increase (in childhood obesity).'

Jan Wright, director of the Child and Youth Interdisciplinary Research Centre at the University of Wollongong, agreed the problem had been exaggerated and dramatised, and said prevention programs needed to focus on improving neighbourhoods with poor facilities, rather than blaming individuals.

A recent United States study found there had been 'no significant increase' in the prevalence of obesity in American children and teenagers from 1999 to 2006, contrary to figures from prior years. The study, published in the prestigious Journal of the American Medical Association, found obesity rates varied by racial group, being higher for non-Hispanic black and Mexican- American girls than for non-Hispanic white girls.

2. Childhood obesity is a complex problem and is caused by factors other than consumption of fast foods

It has been claimed that the problem of being overweight or obese among children stems from a wide range of causes and cannot simply be attributed to an increased consumption of fast food.

The causes of being overweight in childhood are mixed.

The Children, Youth and Women's Health Service claims, 'Part of the cause is due to what the child inherits. The way the body controls energy, uses up fats and feels hungry is different for different people. Some different cultural groups are more likely to be overweight.'

The Service further claims, 'Part of the cause is also in the way children live and what they do. They are more likely to be overweight if they do not get much exercise... Television watching is related to overweight problems because children don't use much body energy when they are watching

they often watch instead of more active play they are likely to have snacks while watching '

There is very easy access to 'energy dense' foods; foods that are high in fats and sugars.

Though it is acknowledge that an increased consumption of high energy-yielding foods, such as fast foods, contributes to the problem it is not the total cause. This involves considering both when and how children eat as well as what they eat.

The Children, Youth and Women's Health Service has further stated, 'Dietary habits that contribute to obesity include often having fast food and large volumes of sweetened beverages such as soft drinks -eating salty foods leads to a child being more thirsty and drinking more, especially more sugar containing soft drinks; eating large portions; skipping breakfast; low intake of fruits and vegetables and irregular meal frequency and snacking patterns,'

Television watching is related to overweight problems because

children don't use much body energy when they are watching

According to statements such as these, though fast foods in significant quantities are not desirable, they are only part of the problem. Defenders of fast food advertising argue that in the face of the complex causal patterns outlined above, targeting fast food advertising is simplistic.

3. Self-regulation of advertising in the fast food industry is already being made more rigorous

A recent voluntary agreement reached among a group of major fast food producers is intended to minimise the promotion of potentially harmful products to children.

In June, 2009, seven companies signed up to the Australian Quick Service Restaurant Industry Initiative for Responsible Advertising and Marketing to Children, modelled on the Australian Food and Grocery Council (AFGC)'s Responsible Children's Marketing Initiative, which came into effect on January 1 this year. The companies - McDonald's, KFC, Pizza Hut, Hungry Jack's, Oporto, Red Rooster and Chicken Treat - have also committed to adopt on-pack nutrition labelling and to display nutritional information clearly on the their websites.

Sixteen leading food and beverage manufacturers have already signed up to AFGC's initiative - including Nestle Australia, Coca Cola, Pepsico Australia, Sanitarium and Campbell Arnott's - with the companies pledging to not advertise to children aged 12 and under, unless they are promoting healthy dietary choices and a healthy lifestyle consistent with scientific standards. The fast-food firms have made a similar commitment, with only healthier choices to be promoted to children under 14.

The latest initiative, which was developed in collaboration with the Australian Association of National Advertisers (AANA), will also provide a transparent process for monitoring and reviewing communications activities. All consumer advertising complaints to do with breeches of the new initiative will be lodged with the Advertising Standards Bureau.

Scott McClellan, CEO of the AANA, has claimed,'An independent third part will also act as a monitor and will be conducting regular reviews to ensue all participating companies are complying with the commitments made in their action plans.'

Participating companies have also said they will work harder to ensure nutrition information is readily available for consumers on their websites and on packaging.

It is also noted that food advertising in Australia is already substantially regulated.

there are already regulations, in the form of codes of practice, which apply to advertising. The regulations currently in existence include the AANA Code of Ethics; the Advertising to Children Code; the Alcohol Beverages Advertising Code; and the Weight Management Code of Practice.

4. If self-regulation of fast food advertising does not work, the government will intervene

Defenders of the Australian Government's current decision to allow fast food companies to self-regulate their advertising have argued that self-regulation will only be allowed to continue so long as it is seen to work.

The House of Representatives inquiry into obesity was chaired by Labor MP Steve Georganas, who has claimed, 'The Government is committed to tackling the obesity problem and will do whatever it takes.'

The report, 'Weighing It Up: Obesity in Australia', states, 'The Committee notes community concerns about the lack of regulation of advertising to children, and supports the argument that marketing of unhealthy products to children should be restricted and/or decreased.

However, the Committee favours a phased approach and thinks that self-regulation may prove successful through the reduction of advertisements for unhealthy food products on television during children's prime viewing times.

But, consistent with a phased approach and industry's own recognition of the limitations of self-regulation, should self-regulation not result in a decrease in the number of unhealthy food advertisements directed at children, the Committee supports the Federal Government considering more stringent regulations on the advertising of unhealthy food products directed at children.'

5. Ultimately, parents are responsible for regulating what their children eat

A number of studies have indicated that parents have a major role to play in effecting their children's body weight, however, it appears that this is not simply whether they agree to supply their children with fast food or not. Critics of fast food advertising maintain that it undermines parents who may then given way to their children's ad-prompted demands for fast food. Others claim, however, that the parents' own exercise and eating behaviours and their awareness of weight as a health issue are both more important.

It has been claimed that parents may have a determining influence on their children's eating and exercising behaviours and therefore on whether their children will have weight issues.

Relatedly it has been claimed overweight parents are more likely to have over-weight children. Some of the reason for this may be genetic; however, it is more likely to be behavioural.

A family's eating patterns can have a major influence on whether children maintain a healthy weight. Some overweight parents may be less concerned about their children also being overweight than parents who have a healthy weight.

A study released in 2006 also suggests that the amount and quality of time parents spend with their children affects whether those children will become overweight or obese. The study was conducted by researchers at Texas A&M University. The five year study found that the more time a mother spends with her child, the less likely that child is to be obese.

It has further been claimed that the parents of overweight children appear to be either less aware of or concerned about the health implications of obesity.

A recent British study concluded, 'Most parents of overweight and obese children did not report poor health or well-being, and a high proportion did not report concern.' This suggests that many parents of at-risk children with weight issues do not perceive their children as having a potentially life-threatening condition. The British study concluded, 'This has implications for the early identification of such children and the success of prevention and intervention efforts.'

Thus, it has been claimed, rather than heavily regulating fast food advertising, it may be more important to educate parents about the dangers of childhood obesity and how to address this problem. The third recommendation of the report 'Weighing It Up: Obesity in Australia' states, 'The Committee recommends that the Minister for Health and Ageing work with state, territory and local governments through the Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council to develop and implement long-term, effective, well-targeted social marketing and education campaigns about obesity and healthy lifestyles, and ensure that these marketing campaigns are made more successful by linking them to broader policy responses to obesity.'