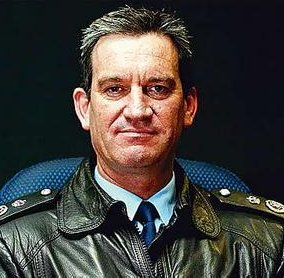

Right:New South Wales police commissioner, Andrew Scipione, has said that a ban on police officers pursuing speeding stolen cars would result in criminals speeding routinely, to avoid being arrested.

.

.

Right:New South Wales police commissioner, Andrew Scipione, has said that a ban on police officers pursuing speeding stolen cars would result in criminals speeding routinely, to avoid being arrested.

.

.Arguments against a ban on high speed police pursuits

1. A ban on high speed police pursuits would allow criminals to act without fear of being apprehended.

It has been claimed that if Australian police were not able to conduct high speed pursuits that would signal to criminals that they could commit offences without fear of arrest.

New South Wales police commissioner, Andrew Scipione, has indicated that a ban on high speed pursuits would be 'unrealistic' as it would send the message to criminals that if they made their getaway at speed the police would not be able to apprehend them.

Commissioner Scipione stated, '...you cannot let ... anyone go out there and think, "Well, if I just go a little bit faster I'll get into a pursuit, police are going to drop off and therefore I've got immunity almost from being arrested or from somebody trying to stop me committing a crime".'

In an opinion piece published in The Punch on March 23, 2010, Paul Colgan asked, 'Is it reasonable to have a policy that says when cops see a speeding vehicle in the middle of the night, they should do nothing?'

The New South Wales Attorney-General, John Hatzistergos, has also indicated that it would be a mistake to abandon police pursuits. Mr Hatzistergos has stated, 'It almost invites people to flee and to avoid the police after potentially having committed very serious crimes.'

Similarly, in 2007, referring specifically to car thefts, Australian Federal Police Association chief executive, Jim Torr, claimed it would be inappropriate to let car thieves believe they could steal without risk of apprehension. Mr Torr stated, 'They'll say, "Let's pinch a car and do burn-outs, we've got indemnity".' Mr Torr went on to claim, 'Canberra is the car-theft capital of Australia.' He suggested that a no pursuit policy would simply increase the number of cars stolen in the Australian Capital Territory.

2. The primary responsibility for any death or injury lies with the fleeing suspect

It has been claimed that it is unreasonable to blame police for harm that occurs as a result of a high speed pursuit. According to this line of argument, the primary responsibility resides with the person who is attempting to escape the police.

In an opinion piece published in The Punch on March 23, 2010, Paul Colgan wrote that families were understandably reluctant to blame dead relatives for accidents they had caused and that there was a general reluctance on the part of both the media and the police to hold publicly accountable those killed in accidents they caused. Colgan argues that this tendency has created a situation where pursuing police are held responsible for deaths and casualties caused by those they were pursuing.

Colgan states, 'The matter of the blame that should lie with him [the driver of the vehicle that caused a fatal accident] has been lost, partly because of the unspoken rule in the debate on road fatalities which is "never to speak ill of the dead".

It's the same unspoken rule that stops police declaring alcohol was involved when a car runs off the road and into a wall late at night when there were no other cars around. Bad enough that a family has lost someone - don't impugn the memory of the deceased by declaring publicly they had decided to drink and drive.'

Defenders of current police pursuit policies argue that the blame for any accident which occurs should lie with those trying to escape apprehension, not with the police officers trying to make an arrest.

3. Harsher penalties are required to discourage criminals from fleeing the police

It has been claimed that rather than prohibiting police from pursuing criminals, the law should make it less attractive from offenders to try to escape. Some police argue that harsher penalties need to be put in place to prevent felons from attempting to leave the scene of a crime at speed.

Senior New South Wales highway patrol officers have claimed that a summary offence introduced in 2006, which set a maximum one-year jail term for people who refused to stop cars upon police direction, was 'hopelessly inadequate'.

One senior New South Wales officer said officers wanted it to be an indictable criminal offence to flee police in a motor vehicle as there needed to be a strong deterrent. After fatal crashes offenders can be charged with aggravated dangerous driving causing death, which carries a maximum penalty of 14 years' jail. But there is no more minor penalty for those who escape a crime in a dangerous manner.

New South Wales Opposition spokesman, Michael Gallacher, has stated, 'The majority of police pursuits were triggered by the driver's reluctance to be picked up for relatively minor traffic matters but when caught, they were only charged with the original offence... NSW law needs to be tidied up and it needs to be toughened up. There needs to be certainty for the police and ... certainty for the courts.'

On February 2, 2010, it was announced that criminals in New South Wales who lead police on high-speed chases would face jail sentences of three years and up to five years for repeat offences, regardless of whether anyone was hurt.

4. Police only pursue as a last resort

It has been claimed that police pursue offenders judiciously and only when there is no other reasonable course open to them. As proof of this it has been noted that in a number of states the incidence of police pursuits has declined.

New South Wales Police figures reveal that the number of police pursuits has fallen from 2227 in 2004 to 1803 in 2009. In 2006 stricter guidelines stated that officers should not give chase if they recognised the car or the driver and could safely pick them up later.

Pursuit guidelines in New South Wales were first overhauled after a 1994 inquiry by the Government's Staysafe committee which led to video cameras being installed in all highway patrol cars. The State traffic commander Assistant Commissioner John Hartley has claimed that pursuits were a last resort for New South Wales police.

In Victoria, under Rule 305 of the Road Rules Act, police and emergency vehicles are exempt from speed limits only if they are engaged in situations such as the pursuit of a vehicle or attending urgent calls for assistance.

In 2001, police vehicles were caught speeding 1171 times by traffic cameras across the state. After police investigations, 1051 were found to be legitimately covered by the legislation. In the remaining 120 incidents all officers were issued with infringement notices.

Victoria Police have developed a "trigger point" system that includes a priority system depending on the severity of a suspected crime. Police chasing a bank robber have more flexibility than police chasing the driver of a suspected stolen car.

Under Victorian guidelines a pursuit should be undertaken only as a last resort when there is no other means of apprehension and when the seriousness of the offence appears to warrant this action.

The pursuit is to be terminated when the potential danger outweighs the need to apprehend. When making this decision consideration is to be given to the gravity of the original offence, the age and competence of the driver being pursued and the prevailing weather and traffic conditions.

The decision to terminate the pursuit can be made by either the officer controlling the pursuit or the officer conducting it.

5. There are operational procedures in place and police training given to protect the community and those being pursued

In New South Wales statewide rules governing high-speed pursuits mean they can be called off for a variety of reasons, including traffic conditions, speed, driving experience of police and the manner of driving of the car being pursued.

In Victoria, the decision to abort a pursuit is left to operational police. Once a chase is declared, a sergeant or senior sergeant in the area is designated the pursuit controller or supervisor. The radio channel is cleared and the chase can be called off if either the police driver or pursuit controller considers it too dangerous. Police are told to balance the need for apprehension against the risk to the community.

Before a member of Victoria Police can drive a police vehicle, they must hold the appropriate Departmental Driving Authority (in addition to a valid Victorian driver's licence). The training and testing of members for these authorities is the job of the Motor Driving School (MDS).

MDS runs a number of different driving courses including:

Standard Operational Car Course

Advanced Driving Course

Four Wheel Drive Course

The instructors are all police members, and all are trained in various instructional techniques and are required to complete the same course that civilian driving instructors undertake. They must also understand the emergency vehicle provisions as they apply to police and Urgent Duty Driving. They need to understand the risks faced by operational members on the roads. They are all highly skilled drivers and many are recreational motor racing drivers.

All police officers must complete the standard operational car course. The advanced driving course must be completed by all officers who wish to act as traffic management unit members.

In Queensland, from January 1, 2008, substantial amendments were made to "police pursuit" rules and guidelines by the introduction of the Safe Driving Policy. This policy involved a major overhaul of the previous arrangements and included a new decision making framework. The new policy included a detailed risk assessment.