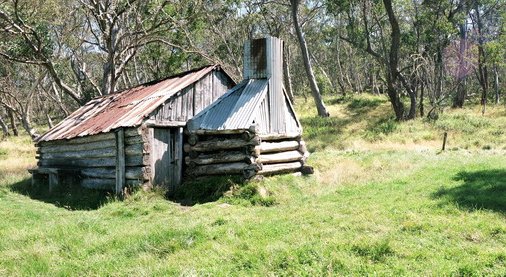

Right: Guy's hut, built (and often rebuilt) by cattlemen as a shelter while working their cattle to and from the mountain pastures. Huts like these dot the mountains and, after cattle were removed from Alpine areas, were used by bushwalkers and four-wheel-drivers. Will they again see use by mountain graziers?

.

Right: Guy's hut, built (and often rebuilt) by cattlemen as a shelter while working their cattle to and from the mountain pastures. Huts like these dot the mountains and, after cattle were removed from Alpine areas, were used by bushwalkers and four-wheel-drivers. Will they again see use by mountain graziers?

. Arguments against cattle being returned to the Alpine National Park

Arguments against cattle being returned to the Alpine National Park

1. Cattle-grazing will damage the Alpine National Park

Matt Ruchell, the executive director of the Victorian National Parks Association, has stated, "In the alpine environment, cattle pollute waterways, trample delicate wetlands, cause soil erosion and spread weeds."

Mr Ruchell went on to explain, "The unique sphagnum moss peat beds and wetlands of the Alpine National Park, and at least 12 alpine plants and wildflowers.listed under the federal law as matters of national environmental significance.are threatened by cattle grazing,"

It has been claimed that the cattle trial is already causing damage to the Alpine National Park, with an early investigation conducted by Dr Henrik Wahren of LaTrobe University's Research Centre for Applied Alpine Ecology showing Alpine Tree Frogs and their wetland habitat being trampled.

Dr Wahren stated, "The wetland habitat of the Alpine Tree Frog is heavily used by cattle, and given the level of damage already observed after just two weeks, it is likely to be severely degraded by the time the cattle are removed for the season in April."

The Alpine Tree Frog and alpine wetlands are listed as nationally threatened under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act.

A Victorian Government desktop study shows that nationally-listed threatened species have been found in the new grazing sites in the past. These species include the Alpine Tree Frog, the only frog known to occur above the winter snowline on mainland Australia, and the Spotted Tree Frog.

Dr Greg Moore, a Senior Research Associate of Burnley College, University of Melbourne, has stated, "Re-introduction of cattle takes us back to the future - a future of environmental degradation and a failure to appreciate the scale and impact of climate change. We should be securing the future of Victoria's alpine ecosystems rather than putting them at risk of further degradation. Doing so is imperative to securing the future of the State as climate changes. Victoria's ecosystems have been under enormous stress and some such as the State's grasslands are among the most threatened in Australia."

2. There is no need for a trial to determine whether cattle-grazing reduces fire risk

It has been claimed that the trail is unnecessary and lacks scientific rigor. One hundred and twenty-five of Australia's principal environmental scientists have written a letter to the Victorian government claiming that `the trials, designed to test whether grazing reduces bushfire, lack scientific integrity'.

Libby Rumpff, of the University of Melbourne's School of Botany, one of the scientists who signed the letter, said the trials set a dangerous precedent for national park management, in that they have failed to recognise previous research.

Critics of the trial claim that there have already been extensive scientific investigations into the supposed fire-preventing effect of cattle-grazing. Each of these studies has failed to find these effects.

The Bracks Labor government removed cattle from the national park in 2005 after an Alpine Grazing Taskforce found cattle damaged the environment and had no influence over fire behaviour.

A peer-reviewed CSIRO study in 2006 also found there were no scientific grounds for the claim that cattle grazing reduced fire risk. The Baillieu government, however, now argues that there is a "general lack of peer-reviewed science'" on the matter.

The most significant research on alpine grazing and fire was carried out shortly after the 2003 fires swept across Victoria's Alpine National Park, and was published in a pee-reviewed journal. The conclusion was that grazing is not scientifically justified as a tool for fire abatement.

The review found that the most flammable fuel types in the park, which contribute almost the entire available fuel load to bushfires, are branches, twigs, bark, eucalyptus leaves and shrubs. With the exception of some shrubs, cattle do not eat these fuels. Snow grass (which the cattle do graze) traps moisture and can be very difficult to burn.

Critics have also argued that this "unnecessary" trial will not produce valid results because it is not being conducted with sufficient rigor. Libby Rumpff, of the University of Melbourne's School of Botany, has noted that the trial design was not peer-reviewed, a normal scientific practice in controversial studies. Dr Rumpff stated, "The only fact that this trial can discover is that cows eat grass."

3. The decision to allow the cattle into the Park was politically motivated

Ted Baillieu's newly elected coalition government had committed to returning the grazing as part of its election campaign. Critics of the promise claim that it was not made with regard to protecting the environment but so as to win or retain the support of rural voters.

The Coalition, as part of its election bid to win back the seat of Gippsland East from independent Craig Ingram, promised the Mountain Cattlemen's Association of Victoria that its long-standing practice of national park cattle grazing would be reinstated. In return, the association campaigned strongly for the election of the Baillieu government.

Libby Rumpff, of the University of Melbourne's School of Botany, has claimed that the Victorian government has used science as a vehicle for political gain. Her argument appears to be that the supposed scientific trial is no more that an attempt to validate what is essentially a political decision.

On January 31, 2011, an opinion piece by Dr Greg Moore, a Senior Research Associate of Burnley College, University of Melbourne, was published on the environment section of the ABC's Internet site. Dr Moore argues, "The re-introduction of cattle must be more about politics than the sustainable management of the alpine environment as I know of no ecologist or environmental scientist who would advocate the re-introduction of cattle for the good of the alpine ecology.'

4. Neither the federal Government nor the Aboriginal custodians of the area were consulted about the trial

A spokeswoman for the federal Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities said the federal Government should have been consulted about the move and was not.

The spokeswoman stated, "Under national environment law, the onus to refer an activity falls on the person carrying out the activity. Any activity likely to have a significant impact on a place protected under national environment law, such as a National Heritage place, must be submitted to the federal environment department to see whether federal assessment is needed."

One hundred and twenty-five of Australia's principal environmental scientists have warned that the Victorian government has potentially broken federal environment law.

Questions have also been raised about the Department of Sustainability and Environment's mapping of federally listed species. The map of the trial sites, published on the department's website, shows only state-listed vulnerable species.

However, departmental information shows there are four federally protected species within the trial sites: the vulnerable alpine tree frog and the endangered spotted tree frog, and two plants, the leafy greenhood and dwarf sedge.

The trial sites are also believed to include alpine sphagnum bogs and fens - sponge-like wetland areas that are listed under the federal Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act as an endangered plant community.

Phil Ingamells, a spokesman for the Victorian National Parks Association, has stated, "We now know there are federally listed species in some of those areas. This is another indication of the haste in which this trial happened. It is an extraordinary oversight by the department."

Critics have claimed that it was not sufficient for the Victorian government to inform the federal government of the trials; it should have sought the permission of the federal government before it began them.

Advice provided by the Environment Defenders Office in January 2011 confirms that the Victorian Government must refer any plans to return cattle grazing to the Alpine National Park to the Federal Government for consideration and approval.

The advice outlines that under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act any action likely to have a significant impact on a "matter of national environmental significance" must be referred to Federal Environment Minister Tony Burke.

Native Title Services has also noted that the Gippsland Gunai Kurnai people may have a case to stop alpine grazing in national parks.

The Gunai Kurnai people were recognised as custodians of the Gippsland national parks at a ceremony in Stratford in 2010. Mr Chris Marshall from the Native Title Services has stated that the State Government failed to notify to Gunai Kurnai people of the changes to grazing.

Mr Marshall said, "There may have been a breach of the Native Title Act by a failure to notify the traditional owners.'

5. The trial has been condemned by Australia's principal environmental scientists

Australia's scientific community has condemned the Baillieu government's decision to return cattle grazing to the Alpine National Park.

In a letter to Environment Minister Ryan Smith, 125 scientists (including some of Australia's top experts in ecology, zoology, fire regimes, wetlands and threatened species) have called for the trials to be postponed.

Concern over the trials has spread to the highest reaches of the scientific community.

In an unusual move, the conservative Australian Academy of Science, a fellowship of the nation's most eminent scientists, has confirmed it is ''taking an interest'' in the issue.

The letter to Mr Smith was signed by 11 professors and nine associate professors.

The experts argue that a panel of independent needed to be involved with the trial from its beginning if its results were to be credible. Their letter states, `The issue of grazing in the Alpine National Park is a highly charged one, and is characterized by entrenched positions amongst stakeholders. Given the divisive nature of this issue, an appropriate governance and administrative structure that ensures transparency and scientific integrity is essential. The provision of high quality science demands independent peer review at the stages of proposal, conduct and communication. This trial has commenced without independent peer review to assess the viability of the research proposal. The establishment of an independent panel of scientific experts to oversee all aspects of the research into cattle grazing in the high country, including its initial design, is necessary to ensure scientific credibility of the current research trial.'

The scientists request that the trial be postponed, at least until it can be set up in what they believe is a proper manner. Their letter suggests that if the proposal had been given full preliminary consideration it may not have gone ahead.