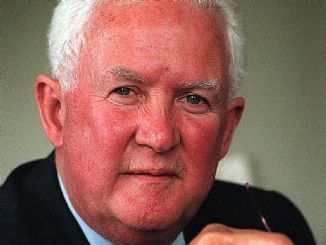

Right: Alistair Nicholson, former judge and current chairman of Children's Rights International, says, 'The whole problem with children is that if you treat them in the same way as offending adults ... you're actively creating more problems for your future.

.

.

Right: Alistair Nicholson, former judge and current chairman of Children's Rights International, says, 'The whole problem with children is that if you treat them in the same way as offending adults ... you're actively creating more problems for your future.

.

. Arguments against fixed minimum periods of detention for 16- and 17-year-olds

Arguments against fixed minimum periods of detention for 16- and 17-year-olds

1. Fixed minimum sentences do not result in a lower crime rate

It has been repeatedly claimed that harsher penalties do not result in reduced crime rates. According to the Victorian Sentencing Advisory Council's 2011 report on imprisonment as a deterrent, harsher punishments were not linked to reduced rates of offending.

Similarly, a study by the Australian Institute of Criminology indicates that people will be deterred by the threat of punishment only if they are rational actors who weigh up the costs and benefits of committing a crime before deciding whether to commit it. This is not typical of violent offenders, nor is it typical of young offenders.

The president of the Children's Court, Judge Paul Grant, has publicly stated there is 'no simple connection between "locking them up" and stopping offending behaviour'.

Judge Grant went on to explain, 'There does not seem to be any connection between higher rates of custodial orders and lower rates of offending.'

Judge Grant further noted that New South Wales detained more children than Victoria, yet that state's crime rate was higher.

Jordana Cohen, a lawyer at the young people's legal centre Youth Law, said that while the proposed changes might be a 'short-term fix to make people happy that there are harsher sentences being doled out, is it going to make the streets safer at the end of the day? Unlikely.'

Studies of Western Australian conviction data also suggest that mandatory sentencing does not have an effect on a criminal's likelihood to re-offend.

Shadow attorney-general Martin Pakula has claimed there was no evidence to suggest mandatory sentences lowered rates of crime or recidivism. Mr Pakula has stated, 'One thing about mandatory sentencing that we know is that there is not a jurisdiction anywhere in the world where it's been shown to work.'

2. Jailing young offenders consolidates and extends their criminal behaviour

It has been claimed that locking young people up tends to increase their likelihood to re-offend. Critics argue this is because a young, impressionable person locked away with others who have committed a serious crime is likely to pick up undesirable habits and attitudes from the others with whom he or she is incarcerated.

The Australian Law Reform Commission's inquiry into juvenile detention concluded, 'The ability of the current detention system to rehabilitate young offenders is increasingly in doubt. A number of submissions to this Inquiry acknowledged its limitations. Detention seems to criminalise young people further. The Law Society of NSW referred to anecdotal evidence that detainees learn to 'play the game' to make themselves eligible for early release and then re-offend following their return to society.'

The Townsville Community Legal Service has stated, '[Detention] can create a revolving door. Children can become more aggressive towards the community and each other, and this can result in them being in trouble with the law again.'

Judge McGuire of the Children's Court of Queensland has stated, 'If young offenders are detained in a detention centre they are out of harm's way for the time being and cannot commit crimes against society. However, detention will not work, if when they come out, they are more criminally inclined than when they went in.'

3. Fixed minimum terms remove judicial discretion

It has been argued that there is no effective difference between mandatory sentencing and fixed minimum terms. Both serve to remove the discretion of a judge as they compel him or her to impose a particular sentence irrespective of the circumstances of the offence.

The president of the Law Institute of Victoria, Caroline Counsel, is among those who have criticised the removal of judges' discretion. She has stated, 'If the community was aware of the myriad of reasons why young offenders commit offences they might stop and pause and realise that you have to preserve judicial discretion in this particular area.'

Referring to the government's proposed changes, Caroline Counsel has argued, 'It's much easier to come out with some trite approach and say all people that commit a certain crime should spend a given period in jail. We say that it's actually more complex than that.'

Jordana Cohan, a lawyer at the legal clinic Youth Law, has specified some of the factors that need to be open to judicial discretion. Ms Cohan has stated, 'We would be very concerned if issues like mental illness, disability, the role of the offender in the circumstances of the offence ... weren't taken into account.'

Alistair Nicholson, chairman of Children's Rights International, has stated, 'The whole problem with children is that if you treat them in the same way as offending adults ... you're actively creating more problems for your future.

You [need to] treat them sensibly and try to reform and rehabilitate them; you're not going to do that by locking them up on a mandatory basis.'

4. Rehabilitation is more effective in protecting the community

It has been claimed that rehabilitation is a more effective means of protecting the community than detention. Under the new sentencing regime young people convicted of violent crime would be detained for two years. If there is no effective effort to change their behaviour patterns then once they are released they may continue to be a threat to the community.

Rehabilitation of the offender gives a greater opportunity of the young person not offending again and this offers greater security to the general community.

The Law Reform Commission's inquiry into youth detention concluded, 'Rehabilitation needs to be established nationally as the primary aim of detention. This is particularly so given the increasing push towards punitive measures in some jurisdictions. As commentators have pointed out, although punishment is rarely cited as an aim of juvenile detention ... it is a prevalent function of juvenile detention. Rehabilitation is beneficial not only to young offenders, but also to the community by assisting the young person to reintegrate into the community. Rehabilitation assists crime prevention by assisting to reduce the commission of further offences.'

5. The public is often more concerned to punish than reform

It has been claimed that governments should not merely follow public opinion on issues such as sentencing. There is, it is argued, a tendency for the general public to react unthinkingly to issues such as law and order, so that their first instinct is to punish where this is not necessarily the most appropriate response.

One of the commentators on the Internet site Skepticlawyer has stated, 'It's natural to sit there and be outraged when you read a brief newspaper report of a 17-year-old who bashed an old grandmother and does not serve a jail sentence. I'd be particularly outraged if it were my relative who was bashed, of course. However, we must always remember when we are reading press reports that we are only seeing a very small part of the information which was brought before the judge, magistrate or jury.'

A Victorian Sentencing Advisory Committee report on popular perceptions of sentencing found that people have very little accurate knowledge of crime and the criminal justice system and that when they are given more information, their levels of punitiveness drop dramatically.

It is argued that the popular tendency to demand harsher sentences than those usually given by courts is based on ignorance and when people are given more information about the complexity of cases or additional information about an offender's background they are more likely to concur with the judge's decision.