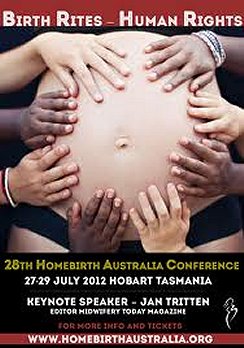

Right: a publicity poster promoting a home births conference.

Right: a publicity poster promoting a home births conference.

Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Arguments in favour of home birth

Arguments in favour of home birth

1. There is little difference in the mortality or morbidity (disease) rate between home births and those that take place in a clinical setting

Data regarding the relative safety of home births compared to those which take place in a clinical setting is difficult to interpret in part because at least in Australia the number of mothers availing themselves of the home birth option is so small (approximately .3 per cent).

However, a recent study conducted in Canada suggests that home births need be no more hazardous than those which occur in a hospital or birthing centre. The study was released out of Ontario and published in the September 2009 issue of Birth journal. It examined the outcomes associated with planned home-birth compared to planned hospital birth, facilitated by midwives, in Ontario over a three-year period (from 2003-2006). The authors found that there is no difference between planned home and hospital birth when comparing peri natal and neonatal mortality rates (or maternal mortality rates, either).

For the baby, the rate of peri natal (relating to the period immediately before and after birth) and neonatal mortality was very low (one in a thousand) for both groups, and no difference was shown between groups in peri natal and neonatal mortality or serious morbidity (disease). No maternal deaths were reported in either setting. All measures of serious maternal morbidity were lower in the planned home birth group as were rates for all interventions including caesarean section.

A longitudinal study conducted in Great Britain which compared the results for home births and those which took place in clinical settings in 1958 and 1970 came to similar conclusions, except it suggests that outcomes were better.

The study concluded, 'Analyses of the published results of national surveys and specific studies, as well as of the official stillbirth statistics, consistently point to the conclusion that peri natal mortality is significantly higher in consultant obstetric hospitals than in general practitioner maternity units or at home, even after allowance has been made for the greater proportion of births in hospital at high pre-delivery risk.'

2. Home birth has been shown to be an advantageous experience in some countries

It has been argued that the home birth experience has many advantages over that of giving birth in a clinical setting and that, in countries where it is an accepted option, the outcomes for mother and child can be better than for those where birth occurs in a clinical setting.

Among the advantages claimed for home birth is that it reduces the rate of what many regard as unnecessary medical interventions. Primary among these interventions is caesarean section, the incidence of which, critics argue, is actually increased by medical management of labour which can disrupt the natural birthing process, thus making a surgical procedure necessary.

Sarah Buckley (MD) claimed in her 2009 publication 'Gentle Birth, Gentle Mothering: A Doctor's Guide to Natural Childbirth and Gentle Early Parenting Choices' that 'Some of the techniques used [in a clinical setting] are painful or uncomfortable, most involve some transgression of bodily or social boundaries, and almost all techniques are performed by people who are essentially strangers to the woman herself. All of these factors are as disruptive to pregnant and birthing women as they would be to any other labouring mammal - with which we share the majority of our hormonal orchestration in labour and birth.'

A 2008 survey of 2,792 mothers conducted through the Fairfax Essential Baby website highlighted the traumatic and unsatisfactory experiences of many Australian women giving birth in an overstretched clinical system. A particularly alienating feature of this system was described as its "one-size-fits-all" service, which dismisses the special needs of individual women. Such experiences fuel women's desire for home birthing.

In the Netherlands there is widespread acceptance of home birthing and approximately one in three births occur at home under the care of a midwife. A 1996 study of the outcomes of 1836 home births compared to those in a clinical setting over the same period found that for women not giving birth for the first time, peri natal outcomes were significantly better for those who gave birth at home than for those who did so in a clinical setting. For first time mothers, managed for risk factors, the outcome was no different to that for women who had selected a clinical setting.

A landmark study by Johnson and Daviss in 2005 examined over 5,000 United States and Canadian women intending to deliver at home under midwife. They found equivalent peri natal mortality to hospital birth, but with rates of intervention that were up to ten times lower, compared with low-risk women birthing in a hospital. The rates of induction, IV drip, episiotomy, and forceps were each less than 10% at home, and only 3.7% of women required a caesarean.

The study concluded, 'Planned home birth for low risk women in North America using certified professional midwives was associated with lower rates of medical intervention but similar intrapartum and neonatal mortality to that of low risk hospital births in the United States.'

3. It should be up to the mother to determine where the birth of her child occurs

Under Australian law, women have the right to determine what, if any, medical treatments they will be subject to. This includes a right to determine the conditions under which they will give birth.

The South Australian government policy on giving birth at home declares 'The woman's wishes for childbirth should be respected within the framework of safety and clinical guidelines. The autonomy of pregnant women is protected in both law and jurisprudence, and it is the duty of health professionals to accommodate that autonomy in as safe a manner as possible for both woman and baby.'

The United Nations has stated that the human rights of women include their right to have control over, and to decide freely and responsibly on, all matters related to their sexual and reproductive health.

Despite declining rates of infant and maternal death, there has been a long-term trend toward increased maternal dissatisfaction with giving birth in a clinical setting. An Australian survey conducted in 2004 found that the main sources of dissatisfaction with birth were the mothers' perceptions of a lack of involvement in decision-making, having 'obstetric interventions' and 'unhelpful caregivers'.

With one in four children being born by caesarean section, many women, their families, midwives and some doctors are seeking a more 'natural' environment for uncomplicated births. Increasingly, emphasis has been placed on the quality of a woman's birth experience. In this climate, supporters of home birth argue that the home birthing option should be more readily available to Australian mothers.

4. Home birth planning should be undertaken and only women with problematic pregnancies should be discouraged from home birthing

There are known circumstances that indicate that a home birth represents an unacceptable risk. Supporters of home birth argue that rather than discouraging all pregnant women from contemplating home birth, each state should have guidelines which clearly stipulate which pregnancies are likely to be safely delivered at home and how this can be achieved.

Australian data have shown unacceptably high risks for the baby from planned home birth for twin pregnancies, pregnancies outside term (37 to 41 weeks) and breech presentations all of which contraindicate home birth. Planned home births, when

meconium is present, also have a higher rate of meconium aspiration than do health unit births.

South Australia has guidelines which state a planned birth at home should be attended by two qualified practitioners, one of whom should be a registered midwife experienced in home births. Appropriate experience with home births should include having participated in at least five home births under supervision.

The qualified practitioner will conduct a careful screening to ensure that the woman's condition is suitable for giving birth at home, that she has no foetal or maternal contraindications, and that she has the capacity to make informed consent.

The guidelines also indicate which domestic circumstances should preclude home birth. These are more than 30 minutes travelling time from a support health unit or hospital; lack of easy access (in case transfer during labour is warranted); lack of clean running water and/or electricity; lack of cleanliness and hygiene; domestic violence; recreational drug use.

It is also recommended that women planning to have a home birth be advised to have the minimum range of tests recommended as part of antenatal care for all pregnant women. The qualified practitioner must have direct access to the results of the tests. Other tests may need to be done depending on the woman's clinical circumstances.

The woman must be provided with an SA Pregnancy Record that must be completed at each and all visits to a health professional.

All women must be offered appropriate counselling on and screening for foetal anomalies. The woman should be advised to have a general medical examination from a general practitioner of her choice before deciding on a home birth to eliminate previously undiagnosed disorders; this assessment should occur early in pregnancy.

It is advisable that a woman intending to have a home birth is booked with a health unit in early pregnancy. In the event of complications during pregnancy, labour, birth or the postnatal period, transfer to a health unit may be necessary.

5. Restricting midwives' access to home births makes it more difficult for women to exercise a free choice

It has been claimed that the fact that there is no Medicare rebate for home birth and virtually no private health insurance rebates are significant impediments to women choosing home birth.

Australia has a national midwifery register. Midwives must be insured to join the register - but private insurers no longer provide cover for births at home and the Federal Government has refused to subsidise professional indemnity for home birth claims. This is not an issue for hospital-run home birthing programs (where midwives are employees of the hospital); however, it is significant for independent midwives and has contributed to a large decline in the last two years of the number of independent midwives who are willing to attend home births. Another obstacle is that mothers cannot claim on Medicare for midwifery expenses where a birth occurs at home. Women and their partners pay around $3,000 to $6,000 for a midwife's care.

Justine Caines, the secretary of Homebirth Australia, has claimed these laws effectively stop registered midwives legally attending home births. Caines has criticised the federal government's position in a submission she made to a Senate inquiry into the new legislation governing midwives and their Medicare coverage.

Ms Caines states, 'The national registration requirement is absolutely appropriate. What is not appropriate has been the [federal government's] response [via its health minister] to say "I will enable the funding of one-to-one midwifery care through Medicare for midwives who care for women birthing in the hospital system, but I won't do it for home birth."'

Given that most international studies demonstrating the safety of home births have been conducted in a context in which qualified midwives were in attendance, supporters of home births maintain that not funding midwives, through Medicare, to attend home births places at risk those mothers who choose home births. It has also been argued that denying Medicare funding in this way reduces the freedom of choice of those mothers not prepared to proceed with a home birth without a midwife present.