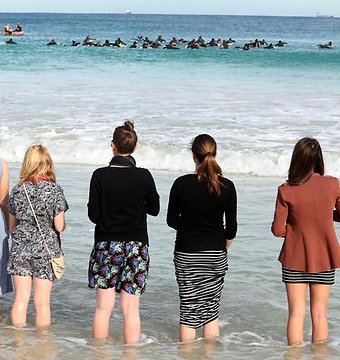

Right: protected by a guard boat and watched by a crowd at the water's edge, surfing friends of a shark victim conduct a memorial service off a WA beach.'

Right: protected by a guard boat and watched by a crowd at the water's edge, surfing friends of a shark victim conduct a memorial service off a WA beach.'

Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Arguments against Australian states using nets, drum-lines and other shark culling measures

Arguments against Australian states using nets, drum-lines and other shark culling measures

1. Sharks do not pose a major threat to human beings

Opponents of stronger shark control measures claim such measures are an over-reaction as the threat sharks pose to human life is generally exaggerated.

On August 2, 2010, Michael Reilly posted a report on News Discovery which included some statistics on the extent of the relative risk represented by shark attacks in the United States and elsewhere. Reilly stated, 'On average, there are about 65 shark attacks worldwide each year; a handful are fatal. You are more likely to be killed by a dog, snake or in a car collision with a deer. You're also 30 times more likely to be killed by lightning and three times more likely to drown at the beach than die from a shark attack, according to ISAF (the University of Florida's International Shark Attack File).'

Reilly elaborated, 'The New England Journal of Medicine reported that from 1990 to 2006, 16 people died by digging until the sand collapsed and smothered them. ISAF counted a dozen U.S. shark deaths in the same period. Clearly, you'd be safer in the water, with the sharks.'

Similar claims have been made in relation to shark attacks in Australia. Based on figures found in the Taronga Conservation Society Australian Shark Attack File, the Taronga Conservation Society Internet site states, 'Compared to fatalities from other forms of water related activity the number of fatal shark attacks in Australia is extremely low. In the last 50 years, there have been 50 recorded unprovoked fatalities due to shark attack, which averages one per year.'

The Taronga Conservation Society site further claims, 'Based on the same calculations used by the International Shark Attack File for the "annual risk of death during one's lifetime" from various activities in America - Australians have a 1 in 3,362 chance of drowning at the beach and a 1 in 292,525 chance of being killed by a shark in one's entire lifetime.'

In a further comparison, the Taronga Conservation Society site notes, 'There is an average of 121 deaths...from people drowning at Australian beaches, harbours and rivers each year (Royal Life Saving Society National Drowning Report 2011). During the period 1969-2000, in NSW alone, 218 rock fishermen were swept off the rocks and drowned. In that same period there were 40 shark encounters recorded in NSW with only two fatalities reported.'

2. Shark culls and other related measures threaten sharks and other marine species

Internationally, shark populations are in serious decline, mostly due to the impacts of fishing, particularly for shark fins which are mostly sold into Asian markets. Some estimates place the decline as as great as 90% of some species. The Australian Marine Conservation Society has noted that an estimated 100 million sharks are killed each year. This equates to 270,000 sharks fished each day. This rate of exploitation is pushing many species toward extinction.

In Australia, although there is less data available, the data there is on shark populations suggests that they are in decline here also.

In Australia, most sharks can be legally caught by commercial and recreational fishers. However, due to declines in numbers, a handful of species are now listed as 'threatened' under the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. Listed as 'critically endangered' are the Grey Nurse Shark and the Speartooth Shark. Listed as 'endangered' is the Northern River Shark. Listed as 'vulnerable' are the Whale Shark, the [Great] White Shark, the Dwarf Sawfish or Queensland Sawfish, the Freshwater Sawfish and the Green Sawfish.

Under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, it is an offence to 'kill, injure, take, trade, keep, or move any member of a listed threatened species on Australian Government land or in Commonwealth waters without a permit'.

Despite this, Queensland, New South Wales, Hong Kong and South Africa are the only places in the world that use shark nets as a means of trying to protect beaches and reduce shark numbers. Shark nets have a serious impact on shark numbers. Since 2008, fisheries data shows that a total of 54 great white sharks have been culled by the netting or meshing programs in New South Wales and Queensland. The nets also inadvertently killed 13 endangered grey nurse sharks during this period.

Dr Carl Meyer of the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology notes that large scale culling 'runs the risk of ecosystem-level cascade effects where a general lack of sharks results in boom or bust in populations of species further down the food chain'.

It is claimed that both shark nets and drum-lines also kill large numbers of species other than those for which they are set, usually referred to as by-catch. New South Wales and Queensland government reports show that the species of marine life caught and killed in the nets used by those states are overwhelmingly "non-target" species, which includes dolphins, turtles, whales and dugongs.

Less than 18 per cent of marine life caught on drum lines in South Africa in the 2011 to 2012 financial year have been great white or tiger sharks, according to statistics published by the KwaZulu-Natal Shark Board - the unit responsible for maintaining the lines in that province. According to the South African report, a humpback whale and an endangered leatherback turtle were among 97 animals caught by drum lines since their installation in February 2007. A Bond University study commissioned by the West Australian Government last year on the best shark hazard mitigation strategy for Western Australia, recommended against the use of drum lines. It was noted in the Bond study that the unintended catch of harmless marine species, including dolphins, would be especially high within the first years that drum lines were deployed, until the population loss lead to a decline in the numbers trapped.

3. Shark culls and other related measures do not guarantee beachgoers' safety

Opponents of many of the stronger measures used to block or kill sharks claim they are ineffective in guaranteeing beach-users' safety.

Shark nets, for example, do not stretch across the entire length of a beach and do not extend from the sea floor to the water's surface. Shark Defence Australia has claimed that 40% of sharks caught in shark nets in Queensland and New South Wales are caught on the beach side of the nets. It is claimed that this demonstrates the nets' ineffectiveness as they clearly allow significant numbers of sharks through to a point where there are human swimmers.

It has further been claimed that baited drum-lines can attract more sharks to an area and so may increase the level of risk faced by swimmers and surfers.

Christopher Neff, an American PhD student at the University of Sydney conducting the first doctoral thesis on the politics of shark attacks, has claimed that West Australian beachgoers would actually be more at risk of attack if the planned drum lines went ahead

Mr Neff has stated, 'I'm befuddled by the rationale of how baiting sharks towards the beaches is meant to reduce the risk of a shark attack.'

Animals Australia spokeswoman Lisa Chalk has similarly claimed that it was common sense that baiting sharks would only attract more, which would increase the likelihood of attacks.

It has also been noted that it seems contradictory for Western Australia to be in the process of banning shark cage tourism because, the Western Australian Department of Fisheries has stated, 'there are concerns that sustained activities to attract sharks to feeding opportunities have the potential to change the behaviour patterns of those sharks' at the same time as the State is going to place drum-line baits for sharks.

Critics of nets and baited drum-lines also claim that their relative ineffectiveness makes them doubly dangerous as they lull swimmers into a false sense of security, leading them to the mistaken belief that they are in a protected area where they do not have to be alert for sharks.

Greens Senator, Rachel Siewert, has claimed in reference to the West Australian measures, 'I think they will give a false sense of security to those using the oceans [and] they won't actually address the issues.'

4. Beachgoers swim and surf at their own risk

Many of those opposed to stronger measures being employed to protect beachgoers from shark attacks argue that this call springs from a misperception about the nature of the marine environment.

There are those who claim that coastal waters are not essentially human recreation areas. Rather, it is claimed, they are marine habitats and are the natural territory of the various marine species that live within them, including sharks. It is further claimed that those who have a genuine respect for the marine environment recognise and accept that they are taking a certain risk every time that they enter the water.

Paul Sharp, an active recreational diver and shark expert, living in Western Australia, has stated, 'I think anybody who genuinely loves the ocean has a pretty realistic understanding of what the real risks are and they choose to take those risks.'

This risk is routinely recognised by those who organise ocean-based competitive swimming events. For example, each year Freshwater, one of Sydney's northern beaches, runs the Barney Mullins Swim Classic. In 2014, the event will be held on Sunday March 2. All competitors are formally advised: 'Ocean swims are demanding and potentially dangerous events. Risks include drowning, natural obstacles, man-made or -controlled obstacles, and marine attack. The Swim takes place in the open ocean. Swimmers enter at their own risk. You should have a medical check prior to entry, and prepare for the event by training. Water safety craft will patrol the course for the duration of The Swim. If a swimmer feels unable to proceed further in the swim, the attention of the water safety personnel should be sought.'

This standard warning is issued prior to all such events and is a clear indication that event organisers and those who take part acknowledge the hazardous nature of ocean-swimming and accept responsibility for their safety.

Western Australia's Department of Fisheries includes the following warning on its Internet site: 'Beaches are aquatic ecosystems. When you enter the ocean, you must remain vigilant of all risks associated with the aquatic environment, including the risk from sharks. While it is impossible to guarantee that you will not encounter a shark while swimming, the risk of shark attack is extremely low, despite the number of attacks in WA in recent years...If you are not happy to accept the risk, albeit low, do not enter the water.'

5. There are a variety of other means that can be used to protect humans against shark attack

Opponents of shark culling in all its forms argue there are other ways of protecting humans against shark attacks.

Firstly, it is claimed, there needs to be a general change in public perception of ocean environments so that all beach-users recognise the inherent risk of these locations. Christopher Neff, an American PhD student at the University of Sydney conducting the first doctoral thesis on the politics of shark attacks, has claimed, 'education means treating a trip to "the beach" like you would a trip to "the bush". This shift in thinking changes our expectations of safety and preparation. Looking at the ocean as the wild, (which it is) means making an informed choice about the risks we are taking based on our behaviour.'

Mr Neff has also suggested that some coastal waters may need to be designated unsafe for swimming or surfing because of shark risk, just as they are because of coastal topography and wave conditions. He has noted, 'In Recife, Brazil, they have made surfing illegal at certain beaches because of the number of shark attacks. Last week, [in the first week of July 2012], the city of Chatham in Cape Cod, banned swimming within 100 meters of seals.'

Mr Jeff has also suggested that beachgoers need to be comprehensively educated about behaviour that contributes to their safety. He claims that the information that needs to be made available is more complex than the warnings which are generally given and notes fifteen environmental/situational conditions which should be avoided if swimmers, surfers and other beach-users are to minimise their risk of shark-attack.

Other techniques that might be used included well-resourced shark-spotting programs. In Cape Town, the Shark Spotters program, introduced in 2004, works at eight beaches. It employs 30 people who spot and record white sharks in the inshore area, warning and evacuating water-users when white sharks are present. The organisation has recorded more than 1,500 shark sightings and the program has been successful at reducing risk.