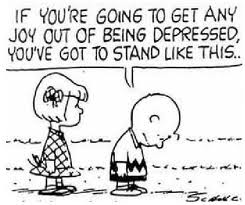

Right: The Peanuts cartoon strip finds a lighter side in this frame. Laughter is considered a potent weapon against depression.'

Right: The Peanuts cartoon strip finds a lighter side in this frame. Laughter is considered a potent weapon against depression.'

Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Arguments suggesting Australia is not doing enough to prevent youth suicide

Arguments suggesting Australia is not doing enough to prevent youth suicide

1. Suicide is a leading cause of death among young Australians

Suicide is a leading cause of death among young people, second only to motor vehicle accidents. Suicide rates among 15-24 year old males have trebled between 1960 and 1990. In remote rural Australia suicide rates for young males are nearly twice those of males living in capital cities. Suicide is rare in childhood (that is, among those less than 14 years of age) but becomes much more common during adolescence. The rise in suicide is most rapid between the ages of 15 and19 years but there is a further increase between the age of 20 and 24 years.

For youth aged 15-24 years, suicide accounts for 20% of all deaths.

Rates of suicide in Indigenous communities have been increasing since the 1970s. The majority of Aboriginal people who suicide are under the age of 29. Overall, the suicide rate in Indigenous communities may be 40% higher than the rate of non-Indigenous suicide.

Suicide has biological, cultural, social and psychological risk factors. The connection between mental disorders and suicide is particularly strong. Serious mental illness such as depression, substance abuse, anxiety disorders and schizophrenia are strongly associated with increased risk of suicide.

The Child and Adolescent component of the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing reported in 2000 that 14% of children and adolescents (14-17 years) experience mental health problems. The national survey also reported that that adolescents with mental health problems report a high rate of suicidal thoughts and that 12% of 13-17 year olds reported having thought about suicide, while 4.2% had actually made a suicide attempt.

2. Young suicidal Australians either do not receive or have to wait too long for psychiatric help

Only one out of every four young persons with mental health problems receives professional health care. Even among young people with the most severe mental health problems, only 50% receive professional help with parents reporting that help was too expensive or they did not know where to get it, and that they thought they could manage on their own.

There have been complaints in individual cases that depressed teenagers have had to wait too long for appropriate psychiatric treatment. In September 2013 it was reported that an Adelaide teenager who subsequently took her own life had been a waiting list to see a psychiatrist for over a year.

Similarly it was reported in November 2012 that there was a six month waiting list for places at the Barrett Adolescent Centre in Queensland.

In 2006 a report was published by a Senate Committee which had investigated the state of mental health in Australia. It made the following comments regarding access to psychiatric help, 'Access to psychiatrists is...very limited. The Australian College of Psychological Medicine (ACPM) submitted that private psychiatrists were largely inaccessible because few bulk-billed, most are located in metropolitan areas and too few psychiatrists are employed in the public sector. ACPM pointed out: "Most [public psychiatrists] are too busy coping with acute crises to be able to become pro-active in prevention and early intervention. Most have no time to deal with the high prevalence disorders such as anxiety, depression, personality disorders and drug abuse, in the main treating the individually very demanding schizo-affective range of disorders."'

The report further notes, 'There is clearly a discrepancy between the available psychiatric workforce and the mental health needs of the population. Dr Martin Nothling, a psychiatrist representing the Australian Medical Association (AMA), said this shortage translated into long waits for patients to see psychiatrists: "...in many cases there can be delays of weeks or months before someone can be seen because psychiatrists are literally so busy."'

3. There is a general reluctance to discuss issues surrounding suicide

Some teachers, doctors and others in Australia and elsewhere are reluctant to discuss suicide with depressed young people for fear it could foster feelings of completing or thinking about the act. However a study published in the May 2011 issue of the British Journal of Psychiatry indicates that this fear is unwarranted.

An initial survey found that 100 family practitioners did not like to ask patients about suicide because they felt doing so might make the patients feel worse. A follow-up survey with patients found that the doctors' fears of adverse results from having their patients discuss their suicidal thoughts were unfounded.

Youth mental health expert Dr Patrick McGorry has stated, 'As a society we have been reluctant to talk about suicide for fear it will inspire "copy cat" behaviour.

We have warned off journalists and editors who believe that the issue cannot be routinely covered.

As a result the media has failed to bear witness to the corrosive effects of these daily deaths on the family and friends of those who take their lives.

Our lack of conversation around the topic has only endorsed the silence that surrounds our young people who often feel too ashamed, too guilty and too stigmatised to put up their hand and ask for help.'

Dr McGorry has further suggested, 'If a young person does feel suicidal it is likely that they are frightened by these feelings.

But so are their peers and parents.

The taboo colludes with the natural desire of parents and friends to hope for the best and assume all is well even though real clues are present.

By asking a young person about these feelings we will give them permission to talk, and in most cases they will feel relieved and better able to overcome periods of suicidality.'

In an article published in The Drum on November 11, 2011, Richard Parker wrote about the importance of those with suicidal impulses being able to talk about their feelings. 'I experienced a terrible, awful low in my life and I failed to seek out the right kind of help. But by talking about my experiences, even now, I feel I can let some air into the basement... and hopefully contribute something meaningful to a conversation about suicide that I believe we simply need to have.'

4. The media sometimes sensationalises instances of youth suicide prompting copycat behaviour

There have been complaints of media outlets sensationalising suicides and risking prompting copycat deaths.

In a recent instance of three Geelong teenagers who took their own lives over a short period in Geelong in 2009 it has been suggested that the media behaved irresponsibly.

Jeff Kennett, the chairperson of Beyondblue has stated, 'We had complaints from family members, we had complaints from the school that some of these journalists were behaving reprehensibly in terms of the suffering that these families were going through at the time, but also it was as though they were actually promoting the deaths.'

Chris Tanti, the chief executive officer of Headspace, has similarly stated, 'Suicide is particularly problematic [area for reporting]and one of the concerns that we in the sector have is that other people, as a result of that reporting, don't go on to take their own lives. And so I think there are ways of talking about suicide that minimise the likelihood that others will, in turn, take their own lives.

Available research suggests that irresponsible media reports can provoke suicidal behaviours. This is referred to as the 'Werther effect'. A strong modelling effect of media coverage on suicide is influenced by age and gender, with vulnerable adolescent girls being particularly at risk.

Media reports are not representative of official suicide data and tend to exaggerate sensational suicides, for example dramatic and highly lethal suicide methods, which are rare in real life.

Dr Michael Carr-Gregg, a psychologist specialising in treating adolescents at Melbourne's Albert Road Centre for Health, believes the impact is substantial, warning that inappropriate media coverage can 'romanticise, glamorise, sanitise and normalise' suicide.

A United States sociologist, Dr Steven Stack, has stated, 'A second (explanation of the impact of the media on suicides) is differential identification with models - in particular, celebrities or well known people who represent the realm of the "superior".' Research identified by Dr Stack has shown that media stories detailing celebrity suicides are 14 times more likely (compared to media stories of non-celebrity suicides) to generate a copycat effect. The media has a responsibility to report on the suicides of celebrities with discretion to minimise this copycat effect.

5. Schools are not doing sufficient to address the issue

It has been suggested that though schools are taking action to address the issue of youth suicide, that currently not sufficient is being done.

In 2010, the then Labor government declared, 'Tragically, an estimated 2-3 high school aged young people die by suicide each week in Australia. As well as doing as much as possible to reduce the incidence of young people taking their own lives, it is critically important to ensure appropriate support is in place for school communities affected by suicide-to support young people whose schoolmates have taken their own lives, and to reduce the chances of 'copycat' suicides.'

Dr Martin Harris, who is on the board of Suicide Prevention Australia, has suggested that a suicide prevention program should be considered as part of the new national curriculum.

'I think it ought not to be the prevail of a particular teacher, but it ought to be a program which is embraced in a robust way by a school when they think they're ready to do it.'

The Gillard Labor government considered that there was a special need among aboriginal children that was not being addressed. The government declared that community leaders need to be trained to better identify and respond to suicide, and activities to better build resilience and positive mental health-for example, in Indigenous communities, brokering visits by elders from communities that have successfully responded to suicide clusters in the past to communities currently experiencing a spate of suicides, to help these communities build their own responses to their community circumstances.