Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Further implications

Further implications

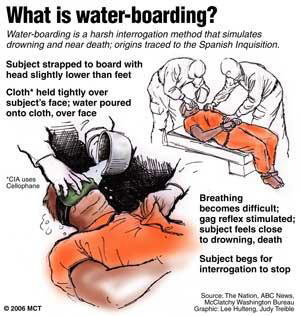

The conflict between morality and national security which is at the centre of debate over whether torture should be used in the interrogation of suspected terrorists is a difficult one to resolve. From an ethical perspective, inflicting extreme 'stress and duress' on someone held in custody is wrong. The advocates of such behaviour claim it is justified by the greater wrong (injury to an innocent civilian population or injury to one's own soldiers) that it is seeking to prevent.

The issue is found in all military conflicts, where protecting one's nation is used to legitimise behaviours that would otherwise be deemed both immoral and illegal. Drawing an ethical line around actions taken when countries are at war is problematic, particularly while the conflict is being played out and countries see themselves as faced with a threat to their survival.

The Geneva Conventions are an attempt to regulate the behaviour of combatants, both in relation to enemy combatants and to civilian populations. There is a significant element of reciprocity in these Conventions. Those participating in a declared war expect that their opponents will treat their captured soldiers with the same respect they have undertaken to demonstrate toward captured enemy soldiers. Similarly, each side expects that civilian populations will not be deliberately injured, killed or otherwise mistreated. It is obvious that these conventions have not always been abided by in many formally declared conflicts in recent times, particularly with regard to the treatment of civilian populations. The immediate brutality of war can override ethical considerations.

Conflicts involving terrorists present even greater problems. Terrorism grows out of an inequality of military power. Groups who conduct terrorist activities generally do so because they do not have the military strength to engage in conventional warfare. Thus, in what is dubbed the 'War on Terror', Islamist extremists commit terrorist acts because they do not have the military forces or equipment that would enable them to declare formal war on those they see as their enemy. In this case they are not even acting on behalf of a particular nation state. Their actions are therefore almost inevitably outside the ambit which regulations such as the Geneva Conventions would authorise. They aim to achieve maximum impact from minimum military capability and so often target civilians. The 'war' they conduct has never been formally declared and is not played by any recognisable set of rules.

In responding to terrorist attacks, most particularly that of September 11, some Western powers, including the United States, seem to have been ready to compromise the rules of conduct that it is hoped will mitigate wartime atrocities. The number of civilian deaths inflicted on Iraq is a case in point. (This case is particularly distressing given that it has since been established that Iraq was not involved in the precipitating terrorist outrage.)

The use of 'enhanced interrogation' techniques is only one dimension of this 'war'. The way out of this moral quagmire is not readily apparent as extreme measures tend to foster reciprocal action.