Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Further implications

Further implications

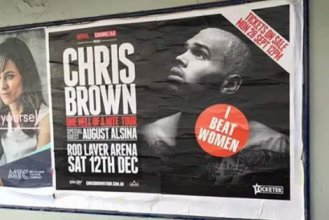

The arguments surrounding whether Chris Brown should be allowed into this country are essentially about the value of symbols. Those camped on either side of this issue have referred to the importance of 'the message we send'.

There are very few who would argue that Brown represents a direct threat to any sector of Australian society. Reading the 'character test' provisions of the Australian Migration Act makes it apparent that the Act is attempting to protect Australian citizens against those whose arrival here might cause immediate harm. Brown is unlikely to present such a risk. There may be some crowd misbehaviour among members of the audience at his concerts, but this is no greater risk than pertains at an ALF football match or at the concerts of any number of other popular entertainers. No one has argued that there is anything specific to Chris Brown R & B singer that would make his concerts particularly unruly.

What appears to be at issue is that allowing Brown into Australia could be read as offering support to those with a history of assaulting women. The concern here is two-fold. Brown's admission might send the message to other young men that it is acceptable to beat up your partner. Equally, concern has been expressed that Brown's being granted a visa could signal to victims of domestic violence that Australia does not care about them.

The first of these concerns seems far-fetched. It is unlikely that allowing Chris Brown into Australia would prompt Australian men to believe that it was OK to assault their wives, girlfriends or children. The justification for doing this is already present in Australian culture. For a significant number of Australian men, inflicting violence upon women would appear to be acceptable because that is what they do.

The impression that is created among Australian women if Brown is denied entry to this country may be more important. Those who see themselves as relatively powerless, need all the symbols and societal support they can find in order to alter this self-perception. It is significant that women's groups around the world have protested against the sale of Brown's records, against the staging of his concerts, against his entry into their countries.

What complicates this issue is that Brown is more than just a focus around which to rally opposition to domestic violence. He is also an African-American. He is, as a number of his supporters and critics have noted, a black man. Why this complicates the issue is that it is culturally less challenging to focus opposition to male violence against women on a man who can be seen as in some way 'other'. As Australia's new Prime Minister has recently stated 'real men don't hit women'. He has further suggested that it should come to be seen as 'un-Australian to disrespect women'. The difficulty with making Brown the figure head for such a campaign is that he is 'un-Australian' and belongs to a generally denigrated racial minority. This makes it all too easy for a majority of Australian men to disavow inflicting violence on women without acknowledging it is something they either have done or might do.

If we are looking for symbols to spearhead a campaign against domestic violence or the assault and murder of women and children we would be far better to focus on Australian celebrities. The ranks of Australia's sporting heroes offer numerous instances of men who have abused women. What these men offer the Australian population are symbols that come directly from home. In rejecting their behaviour, Australian men are challenging themselves. Any real shift in public attitudes has to begin with just such an uncomfortable self-analysis.