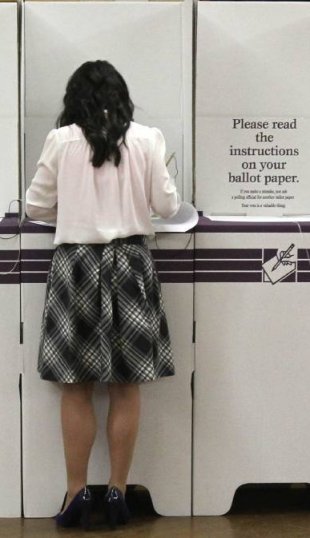

Right: Casting a vote in Australia: it has been suggested that knowledge of the mechanics of voting is not enough and that many Australians - of all ages - are politically ignorant and uninvolved.

Right: Casting a vote in Australia: it has been suggested that knowledge of the mechanics of voting is not enough and that many Australians - of all ages - are politically ignorant and uninvolved.

Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Arguments against extending the vote to 16- and 17-year-olds

Arguments against extending the vote to 16- and 17-year-olds

1. 16- and 17-year-olds lack knowledge and political engagement

Opponents of lowering the voting age to 16 argue that a majority of young people of this age do not have the interest or the knowledge to use the vote wisely. This comment has even been made by some teenagers when referring to their peers.

On November 6, 2015, The Daily Telegraph published a comment by 16-year-old Caleb Bond in which he argues that despite his own strong political interests he considers the majority of his peers too disinterested and uninformed to vote.

Caleb Bond claims, 'Let's be honest, most young people are chiefly concerned with enjoying themselves, and you can't blame them. They're more preoccupied with cars, sport and the opposite sex (especially the opposite sex). You only experience your youth once and if you want to have fun, go for it. Politics takes a back seat and it is evident.

Classmates ask me who the President is. That strikes me as a gaping hole in our understanding of politics as a country.

Australia suffers a great deal of political illiteracy and to throw another group of people in the deep end, possibly even less knowledgeable than some adults, is not wise.'

Similarly, 16-year-old Caulfield Grammar student, Hannah Thomas, has stated, 'I'm against it, really. We're not quite mature enough. Some 16-year-olds would have a fair understanding about all the politics and what Australia needs, I guess, but there are also lots that have no idea.'

Ms Thomas went on to explain, 'We're pretty much isolated in our schools at that age and don't quite understand the full outside world.'

The same views were put forward by two students quoted in a Behind the News segment on youth voting which was telecast on November 10, 2015.

One student identified as Rebecca stated, ' I don't think it's a very good idea because when you're 16 you have other things on your mind, like school and exams, so they wouldn't really make the right decision, they might just fluke it or something.'

Similarly another student named as Georgia acknowledged, 'I personally don't watch the news or read the paper or things like that, so I wouldn't be able to make an informed decision.'

2. The voting behaviour of 16- and 17-year-olds is likely to be highly influenced by others

One argument offered for withhold the franchise from those under 18 is that they are too immature to exercise this privilege independently. According to this argument 16- and 17-year-olds are likely to be excessively influenced by either the significant adults in their lives or by their peers.

It has been claimed that the voting behaviour of 16- and 17-year-olds is likely to be strongly affected by that of their parents. It has been suggested that this means there is no reason to extend the franchise to these young people as they have yet to develop independent political views.

A recent survey conducted in the United States has indicated the extent to which the voting intentions of teenagers are influenced by the voting behaviour of their parents. A 2005 Gallop Youth Survey found that 70% of the young people surveyed claimed to have the same political and social ideology as their parents. The survey also found that there were few differences among demographic groups on this question; boys and girls were equally likely to say that they shared the same political and social views as their parents as were those coming from different ethnic and cultural groups.

The Australian 2004 Youth Electoral Survey (YES) also found that respondents identified 'the family' as the most important source of information about voting in elections, followed by the television, newspapers and teachers. The Australian survey data revealed a gender differential in terms of the family members with whom participants discussed political issues. Male family members, and particularly fathers, were most likely to be mentioned in this context.

A 2011 Australian Electoral Commission review of the influence of parental political leanings on children's' voting behaviour found that young people tend to adopt similar political orientations to their parents. The AEC report stated, 'This is not surprising given that students tend to talk to their parents more about politics, and acquire much of their political knowledge from their parents.'

In an opinion piece published in Mamamia on November 2, 2015, Maggie Kelly further argued that teenagers would be unlikely to exercise an independent vote because they would be prone to the influence of their peers.

Critics of lowering the voting age suggest that to do so potentially damages democracy because it creates a voting bloc particularly vulnerable to manipulation by political parties and others.

3. A significant majority of current voters do not want the franchise extended to 16- and 17-year olds

There is substantial popular opposition to the lowering of the voting age in Australia.

The Australian Electoral Commission's 2013 inquiry into the lowering of the voting age in this country noted, 'In Australia, the public is...opposed to lowering the voting age. ... 94 per cent of the respondents in the 2010 Australian Election Study opposed any change, with 72 per cent saying that the age should "definitely stay at 18".'

Comparing opposition in Australia to that found in democracies overseas, the Australian Electoral Commission states, 'Australian public opinion is more emphatically opposed to lowering the age than is found elsewhere. Overall, just 6 per cent of the electorate favour any change.'

Professor Ian McAllister from the Australian National University has undertaken research which suggests that a significant majority of Australians are opposed to the lowering of the voting age.

Professor McAllister stated, 'Our research on lowering the voting age suggests that first of all there's not a lot of public support for it, less than one out of 10 voters would support lowering the voting age to 16.'

Professor McAllister has suggested that the reasons that the general public found persuasive when the voting age was lowered from 21 to 18 are not seen to pertain when it is proposed that the age be lowered to 16.

Professor McAllister pointed out, 'It was a more potent argument when there was a debate about lowering the voting age from 21 to 18, and it was argued for example in the context of the Vietnam War that people could go and fight for a country but they wouldn't be allowed to vote.'

4. Allowing 16- and 17-year olds the vote would be inconsistent as this age group is not generally regarded as politically, socially or economically independent

It has been claimed that it is inconsistent to allow the vote to 16- and 17-year-olds because our society acknowledges in that in many other areas they are not ready to function as mature adults.

In an opinion piece published in The Guardian on November 20, 2015, Michael White examined the conflicting views currently being exhibited in The United Kingdom where there is significant pressure to extend voting rights to 16- and 17-year-olds.

White writes, 'Scotland, which has now extended the right to vote at 16 to all elections under Holyrood's control, presents the paradox most neatly. The SNP government has tried to restrict the purchase of alcohol at off-licences for those over 18, it may yet try again to raise the age at which people can buy drink to 21 (as in the US).'

White went on to elaborate the range of protective measure in place across the United Kingdom, all of which indicate that society does not regard this age group as mature and independent.

White notes, 'In recent decades, all four home countries and Westminster have piled in to protect the under-18s. In assorted legislation they cannot legally gamble, get a tattoo, buy tobacco, drinks, solvents, paint stripper, possess fireworks in a public place, use a sunbed, sign a property contract, write a will or open a bank account. They can't serve on a jury, appear in an adult court or overnight in a cell (it must be a children's home) or watch porn or extreme violence...'

Professor Ian McAllister has argued that the equity issues that prompted the voting age to be lowered from 21 to 18 do not apply when the proposal is to lower the voting age to 16.

Professor McAllister notes, 'Equity arguments gained considerable currency when the voting age was last lowered. This was the period when the U.S. was embroiled in Vietnam War and of the more than 58,000 soldiers who died in that conflict, one-fifth were less than 20 years old.

The large number of casualties among the young gave rise to the slogan "old enough to fight, old enough to vote".'

It has been claimed, however, that the same imperative no longer applies as though young people can join the defence forces, unlike in the 1960s and '70s they are not being conscripted to do so.

Professor McAllister has explained, 'In Australia, the age of appearing in an adult court and being free to marry is 18 in most circumstances... here are relatively few activities which have a minimum age of 16, with the exception of the age of consent and holding a firearms licence. In short, there is only partial evidence to support an equity argument.'

Regarding the payment of taxation, Professor McAllister observes, 'Most of those in this age category are school students who are financially dependent on their parents. They therefore may pay indirect tax on what they buy, but few will pay income tax.'

5. Giving 16- and 17-year-olds the vote is unlikely to address the causes of political apathy

It has been suggested that the root cause of political apathy is not the age at which voters are first able to exercise this right.

Professor Ian McAllister's research suggests that in countries where voting is not compulsory, lowering the legal voting age actually reduces, rather than increases, the percentage of the population which votes.

McAllister states, 'The evidence from 14 established democracies that lowered the voting age between 1970 and 1992 suggests that in the majority of cases, turnout declined. The estimate is made by comparing the average turnout in the two national elections prior to the change with the average turnout in the two national elections following the change.'

It appears that political interest and involvement generally increases with age and life experience rather than the reverse.

McAllister states his research findings thus,' [I]intended turnout is lowest among the youngest groups-71 percent among those aged 18 to 20, and 68 percent among those aged 21 to 23. Thereafter turnout increases significantly, rising to 92 percent among those aged in their early 30s, before dropping away slightly among those aged in their late 30s and early 40s. This is a lifecycle effect, and reflects the pressures on time due to work and family commitments. For most of the remaining age groups, intended turnout is generally stable, at around 90 percent.'