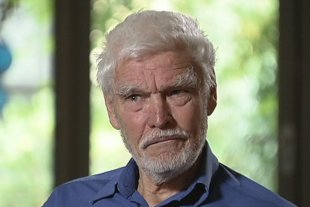

Right: Dr Rodney Syme warns that confining the Victorian legislation to those who are terminally ill would make a bill more politically acceptable, but would not completely resolve the problem.

Arguments against legalising euthanasia

Arguments against legalising euthanasia

1. Despite the Parliament's intentions, if assisted dying is legalised, palliative care is likely to be under-resourced and ultimately less effective and less utilised Some of those who are concerned by the Committee's recommendation that assisted dying be legalised in Victoria believe that such a provision is likely to be implemented at the expense of palliative care. Professor Peter Hudson from St Vincent's Health has claimed, 'If this legislation gets through, the proposal is that if somebody requests assisted suicide, they'd be able to access support from two doctors, potentially see a psychiatrist, and also be allocated a case worker, and I think that's really good and really important that those supports are in place.' Despite his recognition of the value of such supports for those contemplating assisted dying, Professor Hudson and others are concerned that the required level of support will take resources away from palliative care. Professor Hudson has stated, 'However as it currently stands, if somebody has a terminal illness in Australia at the moment, their chances of getting all those supports are very limited. So you have a system where, if you elect assisted suicide you're going to be guaranteed certain supports, whereas if you don't, your chances of getting comprehensive, quality palliative care are less than likely.' Other opponents of assisted suicide argue that over time governments and the medical establishment might actually come to preference it over palliative care because it is less resource expensive. In an opinion piece by Professor Mirko Bagaric published in 1999, Professor Bagaric stated, 'The decriminalisation of euthanasia would provide an alternative means of pain relief and hence a dwindling in the urgency to relieve pain through palliative care. The desire to develop better terminal care or to maintain the current funding for such care would be weakened, if not annulled, and there would be great pressure on the already stretched health budget to redirect funds away from palliative care.' Professor Bagaric concluded, 'Less resources to palliative care means more patients dying in pain, and this constitutes a repudiation of one of the most fundamental priorities of any civilised health system - the immediate relief of pain. The quantity of pain relieved through acceding to the dying wishes of a few is outweighed by the suffering which will be endured by the sizeable majority of the terminally ill who do not want euthanasia but are denied access to appropriate palliative care.' Other critics have suggested that the adoption of a policy of assisted death may result is less care in the management of their symptoms being offered those patients who choose assisted death. The position was put by Roger Woodruff, Chairman of the International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care and former Chairman, Palliative Care Group of the Clinical Oncological Society of Australia in a paper published in 1999. Woodruff stated, 'Patients with advanced disease, who may elect to undergo euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide in the future, are unlikely to receive optimal symptom control, and they will not get the comprehensive and multidisciplinary assessment that is an integral part of palliative care planning for terminal care. A large number of Dutch patients treated with euthanasia were "suffering grievously" or had "unbearable suffering". The only plausible explanation is that they did not receive standard basic palliative care.' 2. The law is able to protect doctors and others giving palliation without legalising assisted dying Opponents of assisted suicide often argue that Australian law offers sufficient protection to doctors and other carers who offer palliative treatment without the intent to kill. They further argue that where, in some jurisdictions, this protection may not be sufficiently explicit, the legal situation can be clarified without the need to legally sanction assisted death. In an opinion piece published on October 15, 2016, the Catholic Archbishop of Sydney, Anthony Fisher noted, 'No one need fear that giving high but appropriate doses of pain relief or withholding too burdensome treatments is unethical or illegal: it is good practice, even if, like the rest of healthcare, it has its risks. Sure, it may in some cases mean the patient does not live as long as they would if we tried everything. But the palliative approach is warranted in such cases and failing to adopt it could well be even more debilitating and life-shortening. All this is well understood in the palliative care world. It does not require changes to law or practice.' In May, 2016, the Australian Human Rights Commission released an Issues Paper titled 'Euthanasia, human rights and the law'. The paper outlines the circumstances under which treatment can be withheld under current Australian law. It states, 'Withholding or withdrawing medical treatment currently occurs in Australia under various circumstances and regulations. First, the Medical Board of Australia and the Australian and New Zealand Society of Palliative Medicine (ANZSPM) states good medical practice involves medical practitioners: Understanding that you do not have a duty to try to prolong life at all cost. However, you do have a duty to know when not to initiate and when to cease attempts at prolonging life, while ensuring that your patients receive appropriate relief from distress. Accepting that patients have the right to refuse medical treatment or to request the withdrawal of treatment already started. The Australian Medical Association (AMA) similarly states that medical treatment may not be warranted where such treatment "will not offer a reasonable hope of benefit or will impose an unacceptable burden on the patient." Regarding the legal sanction for such positions, the discussion paper states, 'Each state and territory has enacted laws to regulate the act of withholding or withdrawing medical treatment with the effect of hastening death. These laws provide for instruments that allow, in a formal and binding manner, the previously expressed wishes of competent adults to continue to have influence over the kind of treatment they receive (or do not receive) when they lose competence... There are two forms of instruments that exist to regulate the withholding or withdrawing of medical treatment: 1) advance directives and 2) enduring powers of attorney or guardianship. All states and territories apart from Tasmania and New South Wales have legislation recognising types of 'advance directive' (variously described across jurisdictions). All states and territories have legislation recognising enduring powers of attorney or guardianship.' Regarding the administration of pain relief which may have the secondary effect of hastening death, the discussion paper states, 'As of the mid-nineties, there had been no criminal prosecutions of doctors in Australia in relation to their administration of pain relieving drugs that have hastened death... Legislation in South Australia, Western Australia and Queensland provides some clarification regarding whether and in what circumstances a doctor providing pain relief which hastens death will be criminally liable.' Opponents of legalising assisted death argue that the law in this area can be clarified to allow for pain relief used in palliation, without having to legalise drugs used with the explicit intent to kill. 3. Once legalised, the circumstances under which assisted dying is employed will expand Opponents of legalising assisted dying argue that once the practice is allowed under law, restrictions such as those foreshadowed by the Victorian Parliament's Legal and Social Issues Committee will gradually be whittled away. There is concern that assisted dying will come to be practised much more widely, in circumstances which many would regard as ethically wrong. In an opinion piece published in The Australian on October 1, 2016, Paul Kelly wrote, 'Where euthanasia is legalised the record is clear - its availability generates rapid and ever expanding use and wider legal boundaries. Its rate and practice quickly exceeds the small number of cases based on the original criteria of unacceptable pain - witness Belgium, The Netherlands, Switzerland and Oregon. In Belgium, figures for sanctioned killings and assisted suicide rose from 235 in 2003 to 2012 by last year. In the Netherlands they rose from 2331 in 2008 to 5516 last year.' Kelly states, 'Claims made in Victoria that strict safeguards will be implemented and sustained are simply untenable and defy the lived overseas experience as well as political reality.' Kelly then goes on to explain the logical progression through which expanded use of assisted dying is likely to occur once the original premise is accepted. He writes, 'If you sanction killing for end-of-life pain relief, how can you deny this right to people in pain who aren't dying? If you give this right to adults, how can you deny this right to children? If you give this right to people in physical pain, how can you deny this right to people with mental illness? If you give this right to people with mental illness, how can you deny this right to people who are exhausted with life?' Kelly continues, 'Once you sanction euthanasia you open the door to euthanasia creep...Cross the threshold and doctors will be encouraged to think it is their job to promote the end-of-life. Sick people, thinking of families, feel obliged to offer up their deaths. Less worthy people exploit the death process for gain. In Belgium children can now be euthanised. Would this have been acceptable when euthanasia was legalised in 2002?' Daniel Mulino's Minority Report (issued as an addendum to the final report of the Victorian Parliament's Legal and Social Issues Committee) cites numerous insistences of people allowed physician-assisted dying in the Netherlands under circumstances which that country's original legislation would not have allowed. These include; the euthanasia after an unsuccessful sex-change operation; euthanasia for anticipated suffering (such as incipient blindness); euthanasia for tinnitus and euthanasia for depression. Critics argue that over time assisted dying can become physician-assisted suicide in response to non-terminal conditions. The response of a number of euthanasia advocates to the Victorian Parliament's Legal and Social Issues Committee report indicates that they see the legalisation of assisted death with the safeguards proposed by the Committee as only the first stage in establishing progressively wider legislation of the practice with fewer of these restrictions. Dr Deb Campbell, a social historian and voluntary euthanasia advocate has expressed disappointment at the legislation proposed by the Committee. Dr Campbell has stated that it will 'merely replace one set of gatekeepers with another, requiring people to get "permission to die from the medical profession". No permission should be necessary, and this issue should be one of civil rights for Victorians, not health care.' Dr Rodney Syme, another euthanasia advocate stated, 'I'm very pleased with the announcement... the success of any legislation depends on how carefully and accurately it is written. I can understand from a political point of view confining it to terminal illness might make it easier for the government and parliament to accept the legislation but I think they need to understand that wouldn't lead to a bill that would completely resolve the problem. In fact the longer a person lives with intolerable suffering the worse that suffering is.' These responses suggest that Dr Campbell believes there should be a right to die, not dependent on a doctor's permission and Dr Syme is here arguing for a reconsideration of the time constraints, so that not only those suffering an immediately terminal illness would be eligible for assisted dying. Dr Syme's comment also suggests that he sees any current limited legalisation of assisted dying as a political necessity for a bill to be passed; however, his position also seems to suggest that he considers the safeguards imposed could subsequently be relaxed. 4. There is no way legally to prevent the misuse of the practice of assisted dying Some opponents of legalising assisted dying also argue that the practice will be misused and that no safeguards or regulatory framework will be able to prevent this. It has been noted that no regulatory system can adequately monitor and control the operation of assisted dying once legalised. Professor Etienne Montero, retained by the Attorney-General of Canada to provide impartial, expert opinion to the Supreme Court of Canada, stated, 'The provisions of the Act, as seemingly strict as they are, cannot be strictly enforced and controlled.' One major problem is systemic under-reporting of cases of assisted dying. Daniel Mulino's Minority Report (issued as an addendum to the final report of the Victorian Parliament's Legal and Social Issues Committee) claims, 'In Belgium, mandatory notification of euthanasia to the Federal Control and Evaluation Commission is a cornerstone of the regulatory arrangements. However, recent reports suggest that around half of all euthanasia cases are not reported.' Critics also note that legalising assisted dying tends to make transgressions in this area more extreme. While they acknowledge that violations currently occur, they are concerned that when the law extends some sanctions to killing, those who break the law tend to do so more severely. Daniel Mulino's Minority Report claims, 'Legalisation simply shifts where hidden activities occur. The argument that a legalized system creates transparency and ensures a clear understanding of what is happening in real life thus needs to be qualified:...there is simply a data shift, with previously hidden practices now regulated, and an increase of other forms of euthanasia, including involuntary euthanasia and practices that do not respect the legal procedures.' It has also been suggested that once legalisation of euthanasia occurs tolerance of transgressions tends to grow. In April 2011, Current Oncology published a paper by University of Ottawa palliative care physician Jose Pereira which stated, 'In all jurisdictions, the request for euthanasia or pas (physician-assisted suicide) has to be voluntary, well-considered, informed, and persistent over time. The requesting person must provide explicit written consent and must be competent at the time the request is made. Despite those safeguards, more than 500 people in the Netherlands are euthanized involuntarily every year. In 2005, a total of 2410 deaths by euthanasia or pas were reported, representing 1.7% of all deaths in the Netherlands. More than 560 people (0.4% of all deaths) were administered lethal substances without having given explicit consent. For every 5 people euthanized, 1 is euthanized without having given explicit consent. Attempts at bringing those cases to trial have failed, providing evidence that the judicial system has become more tolerant over time of such transgressions.' 5. Legalising euthanasia will change medical and social attitudes toward ageing, dying, suicide and disability in a harmful manner It has also been argued that legislative sanction for the deliberate taking of a human life in a medical context is a watershed decision which permanently alters the value system within which the medical profession operates and which has the capacity to alter societal attitudes toward ageing, dying, suicide and disability in ways which might harm the vulnerable. Critics are concerned that legalising assisted dying would fundamentally alter the traditional relationship between patient and doctor. The current president of the Australian Medical Association, Michael Gannon, has stated, 'The current policy of the AMA is that doctors should not involve themselves in any treatment that has as its aim the ending of a patient's life. This is consistent with the policy position of most medical associations around the world and reflects 2000 years of medical ethics.' In an analysis of current Australian law as it effects end of life treatment, Paul Komesaroff, Professor of Medicine, Monash University, has stated, 'In Many doctors have expressed concern that legalising assisted killing would undermine the core values of medicine. Shifting the focus from relieving suffering to terminating life might sound like a small step to some, but in reality it represents a reversal of very fundamental precepts. In medicine, life has never been the disease and death has never been the cure. Rather, the commitment has always been to care for living persons, even in the darkest and most hopeless of circumstances.' Concern has also been expressed that such a shift would undermine patients' faith in their doctors and might lead particularly vulnerable patients, such as those with a disability, to fear that their lives might be considered as of less value. |

Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said.

Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said.