.

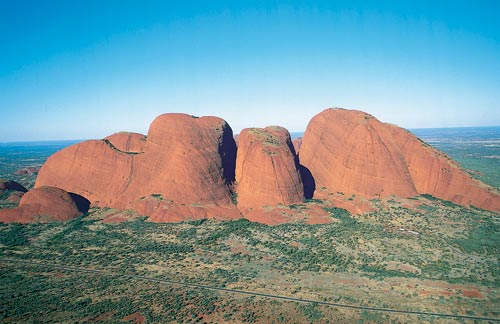

Right: The other, less well known, part of the park, the Olgas / Kata Tjuta. Tourists also damage this site by scrawling on easily-reached flat surfaces.

Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Arguments against banning climbing Uluru

Arguments against banning climbing Uluru

1. Banning climbing Uluru will harm tourism to the area

Supporters of Uluru continuing to be climbed argue that a ban would seriously damage tourism to the area. It has been noted that tourism to Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park and adjoining areas is already in decline. Numbers have been falling for the last decade. From 2004 to 2014, visitor numbers to Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park fell 20 per cent.  At Uluru, Parks Australia has faced some particularly challenging years, as a decline in tourists - from 349,172 in 2005 to 257,761 in 2012 - caused revenue from the sale of entry tickets to fall. At Uluru, Parks Australia has faced some particularly challenging years, as a decline in tourists - from 349,172 in 2005 to 257,761 in 2012 - caused revenue from the sale of entry tickets to fall.

Supporters of the climb argue that there are not sufficient alternate attractions at the Park to compensate for the rock climb being banned. It has been argued that the Uluru Cultural Centre, where tourists are encouraged to begin their visit to the Park and learn about Anangu culture, has not been maintained properly and looks dilapidated, and therefore not an attractive alternative to climbing.

Despite claims that the percentage of tourists visiting Uluru who climb the rock has fallen to between 16 and 20 percent, it is argued that this is not a reflection of what tourists want. Opponents of the ban claim that if tourists felt welcome to climb they would do so. A poll conducted by the Northern Territory News after the ban was announced found that over 60 per cent of respondents were in favour of visitors being allowed to climb Uluru. More than 5,000 readers had responded to the poll by November 11, 2017.

Uluru has approximately 270,000 visitors each year with Australian tourists the most likely to climb the rock followed by the Japanese, according to the Park's figures.  Japanese tourism to Australia is already in significant decline. Tourism Australia's figures indicate the number of Japanese tourists visiting Australia fell to 351,000 in 2009 - less than half the 1997 level of 841,000. Japanese tourism to Australia is already in significant decline. Tourism Australia's figures indicate the number of Japanese tourists visiting Australia fell to 351,000 in 2009 - less than half the 1997 level of 841,000.  External factors such as the global financial crisis have negatively affected the tourism industry throughout Australia, including that to Central Australia; however, critics of the climb's closure argue that such outside pressures as the GFC mean that Australia has to be even more careful not to undermine attractions which draw tourists to this country. External factors such as the global financial crisis have negatively affected the tourism industry throughout Australia, including that to Central Australia; however, critics of the climb's closure argue that such outside pressures as the GFC mean that Australia has to be even more careful not to undermine attractions which draw tourists to this country.

In his tourist advice column, Travellers' Check, published in The Age on December 14, 2009, travel journalist, Clive Dorman, stated, 'I think the ban will do more harm than good if it goes ahead. It will kill off what is left of Red Centre tourism: if you can't personally have what is an exhilarating experience, I think there is no point going there. You might as well look at a picture in a coffee-table book.'

In a letter published in the Sydney Morning Herald on November 4, 2017, Greg Cantori similarly noted, 'It will be interesting to look back from the Uluru settlement ghost town in 20 years and wonder why the tourists stopped coming.'

2. Banning climbing Uluru will financially disadvantage the indigenous community

The Indigenous communities in the region of the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park are already financially disadvantaged. In Mutitjulu, an indigenous community just three miles from Uluru, unemployment, deprivation and poverty are rife.  Aboriginal suicides are at record levels in remote Australia, and the Territory has the highest youth suicide rates in the world. Aboriginal suicides are at record levels in remote Australia, and the Territory has the highest youth suicide rates in the world.  Rates of family violence are by some estimates 30 times higher than in the non-Indigenous community. Rates of family violence are by some estimates 30 times higher than in the non-Indigenous community.

A lack of employment opportunities has been claimed as a major source of Indigenous disadvantage.

It has been argued that allowing tourists to climb Uluru is a source of income for the region and is particularly advantageous to the local Nguraritja and Anangu people. Rather than banning the climb, a number of Northern Territory leaders have suggested that climbing the rock should be more widely exploited than is currently the case.

The Northern Territory Chief Minister, Adam Giles, has stressed the potential advantages to the Uluru Indigenous community of encouraging tourists to climb the rock. At a sitting of the Northern Territory Parliament in Darwin on April 19, 2016, Mr Giles stated that an Aboriginal-supported climb would 'lead to jobs and a better understanding of Indigenous culture'. Mr Giles further stated that promoting climbing of the rock would result in a 'great opportunity for the local Anangu to participate in a lucrative business and create much-needed local jobs'.

Supporting the argument that climbing Uluru should continue because of the economic advantages it can offer Indigenous Australians, Maria Billias, writing in the Northern Territory News, stated, ' Why should we not be encouraging our indigenous Australians to take control of their destiny and harness any economic opportunity that comes their way to help "close the gap"?'

Referring to Chief Minister Adam Giles' claim that fostering Uluru climbing as a tourist attraction would supply employment for Indigenous communities, Billias asks, ' Should the practice of people climbing Uluru be endorsed by Traditional Owners as a means of supporting economic advancement in one of the poorest regions in this country?' Her response is ' The Chief Minister believes so. And he is probably right.'

3. Measures can be taken to reduce safety risks

Supporters of continuing to allow tourists to climb Uluru acknowledge the risks; however, they argue that the hazards can and are being minimised.

The Northern Territory Chief Minister, Adam Giles, has argued that risks can be responsibly managed. Mr Giles has stressed that measures are already being taken to ensure that only those who are fit to do so attempt to climb the rock. Giles has noted that on the Parks Australia Internet site, people are warned not attempt it 'if you have high or low blood pressure, heart problems, breathing problems, a fear of heights or if you are not fit'.

Mr Paddy Uluru, an Indigenous elder who has since died, noted the actions already taken to reduce the risks to climbers and to rescue them should that be necessary. ' Maintenance of the park's vertical rescue capability requires that the numerous staff involved undertake intensive external training and regular in-house training.

Each time an incident occurs several staff and emergency personnel are involved and helicopters are often utilised.'

Further to these existing warnings and rescue procedures, Mr Giles has recommended, 'We could get a professional expert in to look at stringent safety requirements. The climb is not easy. There are safety issues. However, a regulated climb could deliver an unforgettable, unique experience in the heart of Australia's Indigenous culture.'

The same point was made by Maria Billias in a comment published in The Northern Territory News on April 24, 2016. Billias states, ' If safety issues were addressed and more guides were employed to make sure tourists oblige by strict cultural protocols - even if it means keeping the climb closed on certain days or even during entire seasons - then I can only see a potential profitable business opportunity that should be explored.'

4. Uluru is an Australian icon not merely an Indigenous one

Among those who argue that Uluru should continue to be climbed by tourists are those who stress that the site belongs to all Australians, not merely the Anangu people who claim ownership of it.

This was a common thread in reader responses to a news report titled 'Climbing Uluru banned' which was published on November 1, 2017, in The Australian.  The following were among the comments posted. ' What right do any group of Australians have to claim singular title and possession to a landmark that they did not build and which has been there for millions of years longer than them?'; ' It saddens me to think my Australian children, who are as Australian as any of these "Indigenous" people, are now not able to enjoy the same path I did'; ' This is a geological part of Australia. All Australians own it. Same as we all own the beaches, the sun and the trees.' ' You cannot lock up Australian natural icons for circa 3% of the population.' ' What a ridiculous decision. Ayers Rock or Uluru belongs to all Australians.' 'What right have these people got to prevent me from climbing up a rock in my own country? A natural crag in the middle of the desert.' ' Whilst I can respect some indigenous not wanting us to climb it the reality is it belongs to all of us and I do not think climbing it should be banned at all'; ' Ayers Rock belongs to all Australians. If people want to climb it why can't others respect that?'; ' Uluru is owned by all Australians' ; 'Now we can't climb this amazing inspiring piece of our topography because the beliefs of some of the first Australians supersede the rights of all others.' The following were among the comments posted. ' What right do any group of Australians have to claim singular title and possession to a landmark that they did not build and which has been there for millions of years longer than them?'; ' It saddens me to think my Australian children, who are as Australian as any of these "Indigenous" people, are now not able to enjoy the same path I did'; ' This is a geological part of Australia. All Australians own it. Same as we all own the beaches, the sun and the trees.' ' You cannot lock up Australian natural icons for circa 3% of the population.' ' What a ridiculous decision. Ayers Rock or Uluru belongs to all Australians.' 'What right have these people got to prevent me from climbing up a rock in my own country? A natural crag in the middle of the desert.' ' Whilst I can respect some indigenous not wanting us to climb it the reality is it belongs to all of us and I do not think climbing it should be banned at all'; ' Ayers Rock belongs to all Australians. If people want to climb it why can't others respect that?'; ' Uluru is owned by all Australians' ; 'Now we can't climb this amazing inspiring piece of our topography because the beliefs of some of the first Australians supersede the rights of all others.'

Similar sentiments were expressed by a number of posters responding to a Herald Sun report also published on November 1, 2017, titled ' Permanent ban on climbing Uluru to be considered'.  The following were among the comments posted. 'No one owns the rock and never will' ; 'Ayers Rock is an Australian icon belonging to everyone'; ' When will all this pandering to minorities stop and the common good be taken as the priority?'; 'They didn't build it; Nature built it so it belongs to everyone'; 'I was born here and I consider it my rock too'; 'Ayers Rock is 600 million years old. As such there can be no legitimate human claim to 'ownership'. It belongs to the earth; not any one person, culture or race. It belongs to everyone'; 'The Rock was there for thousands of years before the local indigenous laid claim to it and it will be there for thousand more after you and I are gone for all to enjoy. It is there for all to see and if you want to climb it you should be able to do so.' The following were among the comments posted. 'No one owns the rock and never will' ; 'Ayers Rock is an Australian icon belonging to everyone'; ' When will all this pandering to minorities stop and the common good be taken as the priority?'; 'They didn't build it; Nature built it so it belongs to everyone'; 'I was born here and I consider it my rock too'; 'Ayers Rock is 600 million years old. As such there can be no legitimate human claim to 'ownership'. It belongs to the earth; not any one person, culture or race. It belongs to everyone'; 'The Rock was there for thousands of years before the local indigenous laid claim to it and it will be there for thousand more after you and I are gone for all to enjoy. It is there for all to see and if you want to climb it you should be able to do so.'

A letter to the editor written by Peter Waterhouse and published in The Sydney Morning Herald on November 3, 2017, stated, 'The impending closure of the famous Uluru climbing track, while certainly understandable from a sacral point of view, from a social point of view seems to be based on the pretence that the rock is essentially owned by one group of people, rather than to be respectfully shared by all... It forms part of our historic landscape, which should not be denied to subsequent generations, who[se ancestors] simply weren't born early enough to be able to claim an exclusive connection to a natural beauty...'

5. Banning the climbing of Uluru is divisive and will impede reconciliation

Some opponents of the banning of the Uluru climb claim the action is divisive and part of an ethnically-based form of segregation and legal pluralism that will harm good relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Julian Tomlinson, writing in The Cairns Post in an opinion piece published on November 9, 2017, stated, 'Closing The Rock to climbers will likely set off a domino effect of similar exclusion orders around the country.' Tomlinson argues that such exclusions privilege Indigenous laws and customs over those of the rest of Australia and so serve to consolidate divisions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. He writes, 'Those proposing closures say indigenous law should trump the law of the land.

For instance, chairman of the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park board of management at Ayers Rock, Sammy Wilson, said of the native people: "Anangu have a governing system but the whitefella government has been acting in a way that breaches our laws."

This is absurd and divisive.'

Tomlinson further argues that such divisive, segregationist policies are in evidence in other parts of Australia. He writes, 'Locally, entry to Mossman Gorge is controlled by the Kuku Yalanji people...

In the Daintree, the State Government is looking at increasing the role of Aboriginal culture in managing the area. This includes limiting entry to "sacred sites"...

Another example from the Daintree is that indigenous people can take dogs into the World Heritage area, light fires and shoot guns...

In the Hinchinbrook, a big chunk of Missionary Bay is off-limits to anyone who's not a traditional owner without a permit in order to protect "cultural resources", without actually saying what those are.'

Similar concerns have been expressed in relation to a possible ban on climbing Wollumbin (also known as Mt Warning), in New South Wales. Some tour operators in the area are concerned about the divisive impact of such a ban. Mt Warning Rainforest Park's Mark Bourchier has stated, ' I would be very disappointed if they closed the mountain.' However, Arakwal Aboriginal Corporation acting general manager, Sharon Sloane, said the branch would support anyone that attempted to enforce a ban on climbing Wollumbin. She said Wollumbin was 'a sacred men's ground within the Bundjalung Nation' for the Arakwal people.

Concern has been expressed for many years about the potentially divisive nature of a dual legal system in Australia which would recognise some aspects of Indigenous law. The Australian Law Reform Commission's Report 31 titled 'Recognition of Aboriginal Customary Law' published on June 12, 1986, included the statement, 'A view strongly stated in several submissions was that recognition would create an undesirable form of legal pluralism, and that it would be divisive or an affront to public opinion. Proponents of these views argue that there should be "one law for all", and that the goal should be "social equality for Aborigines within the concept of racial unity and integration".'

|

|