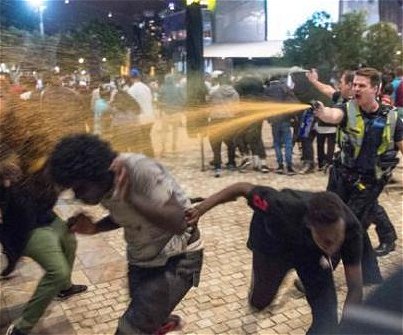

Right: Victorian police use capsicum spray to disperse rioting youths in Melbourne. Incidents like these have made ''African gangs'' a political issue.

Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Arguments that claims about African gangs have not been exaggerated

Arguments that claims about African gangs have not been exaggerated

1. African youths have a high crime involvement relative to the proportion they form of Victoria's population

Those who maintain that Victoria has an African youth gang violence problem argue that young African people are disproportionately represented in crime statistics relative to their representation in the total state population.

In an analysis published by the ABC on January 23, 2018, it was noted that people born in Sudan make up just 0.1 per cent of Victoria's total population, or about 6,000 people.

The same analysis observed that in the year to September 2017, focusing on statistics for alleged youth offenders aged between 10 and 18, Sudanese-born Victorians were involved in 3 per cent of serious assaults, 2 per cent of non-aggravated burglaries, 5 per cent of motor vehicle thefts and 8.6 per cent of aggravated burglaries. This indicates, for example, that young Sudanese are involved in serious assaults thirty times more often than would be expected from their prevalence within the Victorian population.

The same point was made in a report published in The Guardian on January 3, 2018, which noted, 'On the face of it, Sudanese immigrants are over-represented in the crime statistics. About 1% of alleged criminal offenders in Victoria in the year ending September 2017 were Sudanese-born, the Victorian Crime Statistics Agency (CSA) says, while the Sudanese and South Sudanese communities together make up just 0.14% of the state's total population.'

The same Guardian article noted that in particular categories of crime Sudanese youth seemed even more over-represented. For example, 'in charges of riot and affray, people born in Sudan made up 6% of all recorded offenders, compared with 71.5% born in Australia and 5.2% born in New Zealand, a federal parliamentary inquiry reported, citing CSA statistics.'

On April 13, 2017, Andrew Bolt, in a blog published in The Herald Sun, used 2015 crime statistics to make the point that Sudanese youth had a disproportionately high representation in Victoria's crime statistics. Bolt notes, ' Sudanese youths were vastly over-represented in the 2015 data, responsible for 7.44 per cent of home invasions, 5.65 per cent of car thefts and 13.9 per cent of aggravated robberies, despite Sudanese-born citizens making up about 0.11 per cent of Victoria's population.' Bolt underlined the point by concluding, ' Nearly 70 times more likely, then, to commit a home invasion than are Australian-born youths.'

An article published in The Australian on December 29, 2017, used 2016 crime statistics to note, ' Figures from the Crime Statistics Agency show Sudanese and South Sudanese people were 6.135 times more likely to have been arrested last year than offenders born in Australia and 4.8 times more likely than those born in New Zealand.'

In an article published in The Herald Sun on October 19, 2017, related claims were made about the proportion of Victorian's youth prison inmates and parolees which is drawn from what the article refers to as 'high offending racial groups'. The article states ' The...2016-17 Youth Parole Board annual report, reveal(s) more than 40 per cent of the state's youth inmates and parolees were from high-offending racial groups. Africans, mostly from Sudan, represented 12 per cent of the state's youth criminal population.' The other disproportionately incarcerated or paroled groups that the article refers to are Maoris and Pacific Islanders.

2. African youths have been involved in serious offences against persons and property

In addition to noting the proportion of African youth involved in criminal activities in Victoria, those concerned also focus on the type of crime being committed.

In 2014-5 29 offenders born in Sudan were charged with serious assault. In 2015-6 the figure was 50 and in 2016-7 it was 45.

In 2014-5 20 offenders born in Sudan were charged with aggravated burglary. In 2015-6 the figure was 53 and in 2016-7 it was 98.

The violent nature of many of these crimes has been a cause of concern for some commentators, as has the audacity with which they were committed.

Media coverage has highlighted the trauma inflicted on the victims. A report published in The Australian on January 6, 2018, stated, 'A woman was terrorised after being punched in a home invasion in which at least 10 men, described as being of African appearance, broke in and ransacked the property, then threatened to kill her unless she waited at least five minutes before calling for help.

"She's traumatised. I wonder how we'll be able to stay here," a distraught family member, Sam, told The Weekend Australian. "How are you meant to go back to normal after this?"'

In an article published on January 21 in The Herald Sun, Arry Papoutsis, owner of Prowatch Security, stated, 'People are scared because in the past crime would be committed when people weren't home but now crimes are taking place when they're at home - and it's terrifying for people.'

Tarneit resident, Harish Rai, has stated, 'I went for a walk through the park and they were watching me. I heard them laughing and then they came from nowhere. They punched and kicked me. I used to walk every day. Now I know not to.'

Another Tarneit resident, Arnav Sati, was quoted stating, ' People are fearful in their own homes and to walk the streets at night. It has to stop because we deserve the right to feel safe in our community.'

Mr Sati has further stated, 'OK, the 99 per cent across the state are fine, but the 1 per cent who have to deal with it are very, very scared by what they've seen or put up with in their neighbourhoods.'

Former National Crime Commission chairman Peter Faris QC has stated, 'Crime always comes in waves, but this is a very serious one because, as far as we can make out this group, while it might be small, has no respect for people's safety or property.'

3. Traditional definitions of 'crime gang' are not relevant

Those who maintain that Victoria has a problem with African youths committing crimes in groups argue that it does not matter whether or not they conform to the traditional definition of a criminal gang used by Victoria Police.

In Tim Blair's blog published in The Daily Telegraph on January 17, 2018, he ridiculed official Victoria Police definitions of gang violence which excluded that perpetrated by groups of African youths. Blair states ironically, ' There are no African gangs in Victoria...

Instead, there is "just a group of young kids who are going together in a group and they are terrorising people".

A group of young kids terrorising people, you say? Sounds like a gang. But "gang" is forbidden terminology when it comes to our Sudanese brothers. Among polite folk, it's as rare as the verb "rogered" in correspondence between the Bronte sisters.'

Similarly, in a comment published in The Australian on January 6, 2018, Rebecca Urban quoted an informant described as a 'veteran police officer, based in Melbourne's west' who stated, 'If your average Joe Blow in the west is watching the TV news and sees vision of a large group of Sudanese kids mucking up, causing mayhem, what he sees is a "gang".

I think trying to tell the public that it's not a gang, just because it might not meet the criteria of a bikie-style, organised-crime gang, is splitting hairs and it's a big mistake.

The reality is we do have an issue with groups of young men, who largely come from Sudanese backgrounds, who are absolutely obsessed with American gang culture - the music, the clothing the lifestyle, the language - and they're running around town acting exactly like a gang.'

It has been noted that even Victoria Police seems to have shifted somewhat in the terminology it is prepared to apply to groups of African youth who commit violent acts.

On January 2, 2018, Victoria Police Acting Chief Commissioner Shane Patton stated, ' These young thugs, these young criminals, they're not an organised crime group like a Middle Eastern organised crime group or an outlaw motorcycle gang. But they're behaving like street gangs, so let's call them that - that's what they are.'

4. Many young African migrants have destabilised backgrounds and face major adjustment challenges in Australia

Those who attempt to explain why some African youth may be becoming involved in violent crime highlight the particular difficulties facing Sudanese communities. Some of their members have experienced war and many have endured long-term residence in refugee camps. Low levels of education and disruption to families and their traditional value systems have created further problems .

The Sudanese population in Australia is overwhelmingly a young one. Their prior experience of education is limited and their family structures have often been disrupted. The median age of the South Sudan-born residing in Australia in 2011 was 27 years. The age distribution showed 15.5 per cent were aged 0-14 years, 24.9 per cent were 15-24 years, 48.9 per cent were 25-44 years, 10.1 per cent were 45-64 years and 0.6 per cent were 65 years and over.

62 per cent of all Sudanese settlers in Australia are aged 24 years old or younger on arrival. Often it is mothers and children or young people and children, rather than whole family groups who are resettled in Australia.

In addition to those born in Sudan, a significant number of ethnically Sudanese settlers to Australia were born in Egypt or Kenya. The majority of them are children born of Sudanese parents in refugee camps in surrounding countries. Most Sudan-born entrants (79 per cent) described their English proficiency as 'nil' or 'poor' as most Sudanese people speak Arabic, Swahili, Dinka or tribal languages.

Melanie Baak, Convener, Migration and Refugee Research Network, University of South Australia, stated, 'Most families who were resettled in Australia had been living in refugee camps or as urban refugees in Kenya, Uganda or Egypt for at least ten years prior to arriving in Australia.'

In South Sudan less than 30 percent of children attend school. Adult literacy in South Sudan is poor. Only 12 percent of South Sudanese women are literate. This is particularly relevant to the Sudanese community in Australia as many families from Sudan are headed by single mothers.

In an article published in The Sydney Morning Herald, on January 2, 2018, Kate Habgood, who teaches African students at a Melbourne high school suggests the impact that years of living as a refugee could have on students. She states, 'Students who have come from South Sudan, Sudan and Somalia may have lived in refugee camps all their lives. The skills needed to survive in a camp can be very different from the compliant behaviour expected in an Australian classroom. The frustration that arises from having your life and future livelihood beyond your control, for years on end, in the hands of a remote UN organisation, is difficult to imagine.'

It has also been argued that Sudanese families in Australia often make a difficult transition as child-rearing practices are very different between the Sudanese and African cultures. A 2016 Victoria University study on Sudanese parenting practices in Australia quoted one Sudanese parent who stated, 'Here as parents, we face a lot of challenges. Parenting practices have changed a lot here. For example, a child has a right to say anything, even not listening to his/her parent...you can't force your child to listen to you.'

Africa Media Australia chief executive Clyde Salumu Sharady has stated, 'Kids are growing with very little structure within families, many of them don't have male figures in their families. Child protection laws are actually fuelling this crisis. There has got to be some understanding of the cultural background of people. In most African families, the rearing of the children is a little on the tough side rather than being very permissive. When that happens it is easy for child protection services to go in and qualify that as abuse and remove children from parents and that actually makes things worse.'

Kot Monoah, chair of the South Sudanese Community in Victoria notes, 'Typical South Sudanese culture is one of strict upbringing. We need to help parents find alternative parenting, if we all of a sudden say that strict parenting is not the way to go in Australia.'

5. Young African migrants are economically disadvantaged, often unemployed and face discrimination

Those who attempt to explain why some African youth become involved in violent crime stress the significance of economic disadvantage and unemployment.

Dr Berhan M Ahmed, head of the African Australian Multicultural Employment and Youth Services and a Research Fellow at the University of Melbourne, has stated, 'Crime has many roots, but the most important root is poverty. We need to understand that it is the combination of poverty and hopelessness that produces violent crime.'

At the time of the 2011 Census, the median individual weekly income for the South Sudan-born in Australia aged 15 years and over of $272 was approximately half that of the rest of the Australian population when compared with $538 for all overseas-born and $597 for all Australia-born.

This low weekly income is attributable to low participation in professional or highly skilled fields of employment and to a high unemployment rate. As indicated by the 2011 census, of the 1028 South Sudan-born who were employed, only 18.8 per cent were employed in either a skilled managerial, professional or trade occupation. The corresponding rate in the total Australian population was 48.4 per cent. Among South Sudan-born people aged 15 years and over, the participation rate in the labour force was 50.7 per cent and the unemployment rate was 28.6 per cent. The corresponding rates in the total Australian population were 65 per cent and 5.6 per cent respectively.

In some areas, the level of unemployment among African youth is even higher than the overall figures suggest. Such elevated levels of unemployment can have a very negative effect on the communities involved.

In an article published in The Age on April 21, 2017, Abeselom Nega, a board member of the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission, stated, 'Unemployment is at 40-50 per cent in some African and Pacific Islander communities. By the time kids reach 17 or 18, they know they have very little chance. They have very little skill, they don't have the language to compete in the market effectively, they can't go to uni or TAFE or become a tradie. It's a hopelessness.

There are a lot finding it very difficult to get a job and I am even talking about the African kids who have gone to uni and do the right thing for themselves and for their families. They are struggling, too.'

It has been suggested that racism in addition to a lack of qualifications is making it difficult for Sudanese Australians to find employment. A recent study in the Australian Capital Territory found that while 42% of the 72 South Sudanese participants had tertiary qualifications, 96% of this participant group were seeking employment - with many unemployed or underemployed, despite their qualifications.