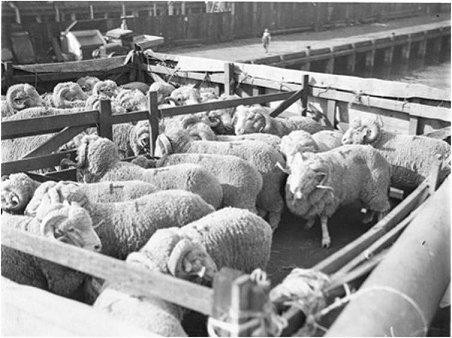

Right: Sheep on an above-deck pen in Sydney Harbour in 1929. Even at this time, complaints were made over the treatment of livestock exported in boats. However, the complaints were mainly made while the animals were in transit to the docks. Once out of public sight, the animals were at the mercy of the exporters.

Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Arguments in support of banning live animal exports

Arguments in support of banning live animal exports

1. The live transport of animals from Australia is cruel and morally unjustifiable

The cruelty involved in the export of live animals has been repeatedly exposed by an number of animal welfare groups.

The traumatic and unsanitary conditions have been stressed. On live-export ships, particularly during long journeys, animals may be forced to stand for a substantial period of time in a slurry of water, faeces, and urine up to 45 centimetres deep until they are unloaded. On a number of vessels, faeces can fall from upper levels to the decks below, landing either on the animals or in their feed or water troughs. Cleaning is spasmodic, and thousands of tons of effluent are dumped overboard before arrival at the port.

Animals Australia has described the consequences of heat and the accumulation of urine and excrement in this manner: ' When temperatures soar - and predictably they do - weeks of untreated waste build-up 'melts' into a thick, deadly soup. Any animal needing to lie down to rest risks being buried in excrement. Corrosive ammonia chokes the air and burns the eyes and throats of those on board. Distressed animals rapidly overheat. Their hearts race as they gasp for oxygen.'

Cramped conditions and inadequate ventilation combined with high temperatures and humidity lead to serious illness. Indeed, heat-stress mortality has been an issue since the beginning of the trade. As recently as 2013, it resulted in the deaths of more than 4,000 sheep on the Bader III - and most of these deaths occurred in a single day.

Rough seas are also a significant problem, resulting in suffering as well as mortality. The smaller the vessel, the greater the risk that animals will be injured by its movements in heavy seas. The highest mortality rates for cattle on live-export ships in the last 20 years have been the result of turbulent waters and inclement weather. In some instances, up to 75 per cent of the animals aboard have died.

The 60 Minutes report which provoked the current controversy televised footage which showed hundreds of Australian sheep, cramped together and dying aboard squalid live export ships headed from Australia to the Middle East. The video, filmed by a navigation officer on board multiple voyages, showed thousands of animals packed into ship's pens, panting in the extreme heat.

More than 1300 sheep allegedly died in two days during an intense heatwave in the Persian Gulf.

The RSPCA's Internet site has a timeline of animal cruelty episodes associated with live animal export from Australia. Forty-four episodes involving animal cruelty are listed between February 2014 and March 2018.

Also of concern is the manner in which the animals that survive this transport will be slaughtered on arrival. Despite regulations imposed by Australia that are meant to ensure humane treatment of these animals, there is evidence that these regulations are frequently not followed.

2. Past attempts at reform have not been effective

Critics of the live animal export trade in Australia argue that despite a long-standing history of inquiries followed by attempted reform, animal mistreatment continues to occur.

In 1985, a Senate inquiry into the export of sheep from Australia to the Middle East

concluded that 'if a decision were to be made on the future of the trade purely on animal welfare grounds, there is enough evidence to stop the trade. The trade is, in

many respects, inimical to good animal welfare, and it is not in the interests

of the animal to be transported to the Middle East for slaughter.'

The General Conclusions of the report recommended the trade should continue provided that the welfare of the sheep was given the proper high priority it requires.

Critics of the trade argue that the recommended 'proper high priority' has continued to be denied to the animals being transported.

The 2003 Keniry Review, which drew on the findings and recommendations of a Government-established Independent Reference Group (IRG) in 2000 and 2002, found problems with enforceability under the existing framework and again stressed the need for national, mandatory standards.

The fundamental recommendation of the Keniry Review - that the Commonwealth government be responsible for the regulation of the industry - was adopted and thus the government is currently in charge of the live export industry. The Explanatory Memorandum of the Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry Legislation Amendment (Export Control) Bill 2004 indicated that the government accepted the recommendation that national standards be developed. Some critics, however, have suggested that this was not actually achieved because there is no requirement that the standards be reviewed by Parliament.

Despite the introduction of the Exporter Supply Chain Assurance Scheme (ESCAS ) in 2011, reports of supply chain breaches have continued alongside criticism of the effectiveness of the existing enforcement mechanisms and procedures. The Australian Greens, animal welfare advocates and some exporters have argued that the regulatory scheme remains ineffective in the absence of enforcement action.

3. Australian regulators have not been sufficiently rigorous

It has been claimed that the number of livestock deaths aboard transport ships has been misstated or underrepresented and that these discrepancies have been ignored by Australian regulators. It has further been claimed that even where it has been openly acknowledged that animal morality rates have been above accepted levels no adequate action has been taken by Australian regulators.

On October 26, 2017, an ABC News report stated Vets Against Live Exports (VALE) was highly critical of the counting methodology used in a voyage of the sheep livestock carrier Al Messilah, where the Federal Department of Agriculture (FDA) report noted that 1,741 sheep had died. The report, however, conceded that it was impossible to verify the actual number of deaths, as 1,286 animals 'could not be accounted for'. An FDA spokesperson said that this was because of an 'inability to collect or dispose of carcases' due to decomposition and decay of dead bodies.

VALE's Dr Sue Foster commented that the final death figure could and should have been reached by simple arithmetic. 'Normally the mortalities are counted as the number loaded minus the numbers unloaded because the only reason for sheep not being there is they died,' Dr Foster said.

These figures are significant as an investigation is supposed to be conducted by the FDA after long-haul voyages when mortality rates of 2% for sheep and 1% of cattle are reached.

A misstatement of mortality figures enables transport companies to sidestep an investigation.

A misstatement of mortality figures enables transport companies to sidestep an investigation. A report published in The Guardian on April 10, 2018, claims that even when mortality rates have been acknowledged to exceed the levels at which an investigation is meant to take place this either does not occur or negligible penalties are imposed.

Animal welfare groups claim that shocking conditions such as those recently shown on 60 Minutes in footage of the Australian live export ship Awassi Express on which more than 2,000 sheep died are not uncommon. It is claimed such conditions have been repeatedly reported to the federal regulator. The concern is that insufficient action has been taken and that monitoring should not have to depend on the actions of whistleblowers.

The federal agriculture minister, David Littleproud, has announced a review into the 'culture' of the federal Department of Agriculture after it failed to uncover the recently publicised animal welfare violations exposed by a whistleblower.

An analysis by Guardian Australia of 70 mortality investigation reports produced by the FDA shows a number of cases where conditions contrary to Australian Standards for the Export of Livestock (ASEL) are noted in the report. Despite this, Guardian Australia found no instances of punitive measures such as fines or loss of export licence being imposed. The department was asked to provide details of any companies that had been punished for breaches of the standards, but it did not respond.

4. Humane transport conditions for live export animals are not economically viable

Opponents of the live export of Australian livestock argue that the expense required to transport the animals in ways that would not inflict unacceptable levels of suffering is too great to sustain. The costs involved would have to be borne by either exporter or importer and they would be too great for either party to consider.

Liberal Party MP Sussan Ley has refused to support the Federal Government's proposal to further reform the export trade and has brought her own private member's Bill to phase out the live sheep export trade altogether.

A sheep farmer for 17 years and representing a regional New South Wales seat, Ms Ley argues that the expense associated with humane transport is too great to be economically sustainable. Introducing her Private Member's Bill, Ms Ley told Parliament that the trade 'can only survive profitably on the business model of animal cruelty. More humane conditions would render it unviable.'

The Turnbull Government has announced a series of reforms to the $250 million live export industry including more room for sheep on ships and reducing the number of animals aboard. These stricter rules are intended to make sure sheep have access to places to rest, access to adequate food and water and can be in a position where they will not be exposed to heat stress.

Ms Ley has responded to the government's proposal by claiming, 'It's impossible to transport animals humanely over long distances...it wouldn't be commercial. I watched the [live export] industry for years and...have reluctantly concluded that the industry has no foundation either economically or from an animal welfare point of view.'

Ley has elaborated, 'If the rules were actually enforced - access to feed, water and rest, avoiding high heat stress, no commercial operator would undertake the trade. Exporters have explained to me that it would not be viable. Unfortunately this is an industry with an operating model built on the suffering of animals.'

Ms Ley told Parliament the trade only exists because it is subsidised by Qatar and Kuwait. Ley stated, 'The live sheep trade is in terminal decline, dropping by two thirds in the last five years. It is based on just two customers in two countries, Kuwait and Qatar who account for 70 percent of exported sheep. The demand for live sheep comes from its cheap retail price due to government subsidies, not cultural or refrigeration reasons. 99 percent of consumers in the Gulf have refrigeration.

Every Middle Eastern country accepts Australian Halal slaughter.

However, the subsidies are being phased out. Bahrain ended theirs in 2015 and went from 325 000 live sheep from Australia to zero. '

The withdrawal of subsidies is likely to accelerate if further regulation to promote animal welfare increases costs. Ley argues that Australia needs to transition to a boxed and chilled meat model that is both humane and economically sustainable.

The withdrawal of subsidies is likely to accelerate if further regulation to promote animal welfare increases costs. Ley argues that Australia needs to transition to a boxed and chilled meat model that is both humane and economically sustainable. 5. Ending live sheep and cattle exports will not damage Australian farmers

Opponents of live animal export argue that it is not necessary for the economic wellbeing of Australian farmers. They claim that the animal export trade is already in substantial decline and that farmers have diversified what they grow and produce and how they export their meat products so that they are no longer reliant on exporting live animals.

Writing in The West Australian, on May 23, 2018, columnist Paul Murray contended that: 'The numbers don't lie. This is an export trade in terminal decline and the natural reduction over 15 years poses real questions about the arguments that some farmers will go to the wall if it ends.'

Murray clearly argues that if farmers have survived the current decline in the live export trade, they will be able to survive its termination.

On June 7, 2018, Tony Zappia made the same point in an article published in The Advertiser. Zappia wrote: 'The industry is already in decline with live sheep export numbers falling from seven million in 1988 to 1.7 million in 2016-17, whilst exports of chilled and boxed meat to the Middle East increased tenfold between 2006 and 2016.

According to Meat and Livestock Australia the sheep meat industry was worth $5.2 billion in 2016-17. Live sheep exports accounted for less than $250 million - or five per cent - of the industry's value.'

A week and a half later, on June 18, 2018, The Sydney Morning Herald published a comment by Susan Ley, federal member for the rural seat of Farrer. Ley states: ' The live sheep export trade is already in decline. Between 2010-11 and 2016-17 the value of Australian lamb exports to the Middle East increased by more than 100 per cent and our mutton exports by 25 per cent. In comparison, during the same period our live sheep export trade to the Middle East decreased in value by 27 per cent and the number of live sheep being exported more than halved.'

It has been judged that Australian sheep farmers would be able to transition from a business model that completely or largely excluded the sale of live sheep. In an article published in The West Australian on April 15, 2018, Paul Murray notes that a recent report had found 'the overall economic effect on WA of ending the trade would be marginally positive because of the effect on the abattoir industry which had sufficient spare capacity to absorb all the live sheep exported annually from WA.'

Though not as dramatic, similar trends are apparent in live cattle exports, indicating a gradual fall in the market which will ultimately require the local industry to adjust. In an article published in The Herald and Weekly Times it is noted: 'Australia's largest cattle live export market, Indonesia, took 146,803 cattle for the four month period, 8 per cent fewer than the same time last year, while for the 12 months to April Indonesia took 499,740, down 14 per cent.'

For both Australia's cattle and sheep exporters, boxed and chilled meat makes up by far the largest percentage of the market. The live-animal trade is minuscule compared to the boxed and chilled export component. In 2012-13 only 6 per cent of cattle and 7 per cent of sheep raised for meat were exported live.