Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Further implications

Further implications

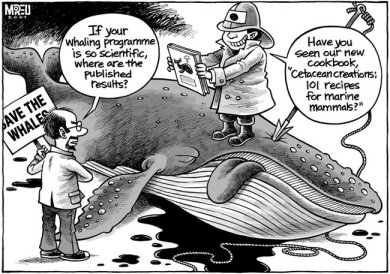

The withdrawal of Japan from the International Whaling Commission(IWC) had become inevitable. The Commission was originally established to oversee the sustainable exploitation of whales by countries involved in the industry. It has become a body exclusively devoted to whale conservation. In 2017 Japan failed to have the Commission lift its 30-year moratorium and allow commercial whaling.

Responding to Japan's withdrawal from the IWC, Natalie Barefoot, a University of Miami law professor and expert in whale law, has argued that it would be better to have all whaling nations operating under the oversight of an international regulatory body than acting independently. Professor Barefoot has stated, 'As we become an increasingly global community, it's better to have everyone at the table, even if you disagree, and just to continue to work. These are global issues we're addressing, and we need to address them together.'

What Professor Barefoot's comment fails to acknowledge is that the IWC had ceased to function as a body through which conflicting views could be addressed and resolved. There had ceased to be any possibility that those nations wishing to continue commercial whaling would be able to find a place at the table and have their practices endorsed sufficiently so that they could be regulated by the IWC.

Japan has consistently been treated in a manner which it has condemned as unjust and prejudiced. There are still a small number of Japanese communities which can claim a strong cultural connection and an economic dependence on whaling. Japan has regularly made representations on their behalf to the Commission but these have been ignored. This has been seen by the Japanese government as inequitable as the IWC allows various indigenous groups around the world to hunt whales for 'subsistence'. For example, the people of the Caribbean island of Bequia hunt humpbacks, even though they learnt whaling only 150 years ago, from New Englanders. In Taiji, on Japan's main island, memories of whaling are more recent and the tradition many centuries old. People have family names like Tomi ('lookout') while stone monuments along the coast honour the spirits of whales, whose meat sustained the town through famines.

Despite such strong cultural connections the IWC has not made exemptions that would allow these communities to continue whaling.

Despite such strong cultural connections the IWC has not made exemptions that would allow these communities to continue whaling.Effectively, successive Japanese administrations have seen IWC bans on commercial whaling activities as an unjustifiable restriction of Japanese national and cultural sovereignty. Thus Japan's ultimate withdrawal from the Commission has long seemed inevitable. In a thesis published in 2016, Mika Ranta predicted, ' The only way to truly save face, safeguard international legitimacy of the state and reputation while continuing whaling in the future, would be to resign from the restricting and stalling regulatory framework and continue to whale completely under domestic controls.'

What is regrettable is that a situation has now been created in which Japanese whaling will be conducted completely outside the regulation or even the observation of any international body.

The Japanese government plans to allow whaling in Japan's huge territorial waters. A small local fleet has survived by hunting cetaceans not covered by the IWC, such as dolphins and Baird's beaked whale, and by conducting 'research' of its own. Freed from the Commission's constraints, it might increase its catch from 50 minke whales a year to 300.

This is similar to the number previously being taken from Antarctic waters for research. The difficulty here, however, is that the number of whales to be harvested in this manner is far fewer. As Peter Bridgewater, a former IWC chairman, warned, 'Japan is giving up catching minkes from a healthy population in the Southern Ocean in return for catching unmonitored numbers from a population in the north Pacific whose health is much less certain.'

This is similar to the number previously being taken from Antarctic waters for research. The difficulty here, however, is that the number of whales to be harvested in this manner is far fewer. As Peter Bridgewater, a former IWC chairman, warned, 'Japan is giving up catching minkes from a healthy population in the Southern Ocean in return for catching unmonitored numbers from a population in the north Pacific whose health is much less certain.'

The inflexible moratorium imposed by the IWC on Japanese whaling did not make adequate allowance for the political situation in Japan. The number of people actively affected by the moratorium is very few, but from the point of view of a country sensitive to infringement's of its national autonomy the ongoing rejections had to become politically damaging to any government. For conservatives in prime minister Shinzo Abe's Liberal Democratic Party, whaling is a nationalist emblem.

In an era of growing nationalism around the world, as indicated by the Brexit movement in Great Britain and the United States growing isolationism under Donald Trump, the assault to national pride represented by constant rebuffs from the IWC was unlikely to be accepted indefinitely by Japanese governments.

In an era of growing nationalism around the world, as indicated by the Brexit movement in Great Britain and the United States growing isolationism under Donald Trump, the assault to national pride represented by constant rebuffs from the IWC was unlikely to be accepted indefinitely by Japanese governments. Peter Bridgewater has concluded, 'This is a moment of breakage and pain for the international system, driven partly by political manoeuvring in Japan, but enabled by rote chanting in the West of "we don't like killing whales".'