Right: Satire: Australia's attitude to conscription, especially wartime conscription, has often been influenced by the working class's suspicion of conservative politicians' motives, as is shown by this World War One anti-conscription poster.

Right: Satire: Australia's attitude to conscription, especially wartime conscription, has often been influenced by the working class's suspicion of conservative politicians' motives, as is shown by this World War One anti-conscription poster.

Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Further implications

Further implications

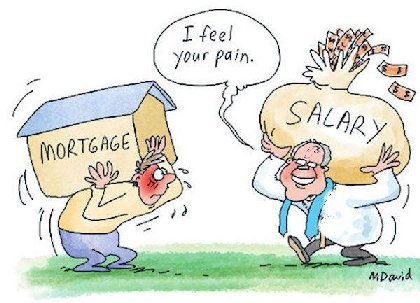

The perception that Australian politicians are extravagantly paid by world standards is probably exaggerated.

Australia's prime minister, Scott Morrison, currently earns 6.4 times the average wage. This places him sixteenth on the list of world leaders ranked by level of remuneration relative to what their countries' citizens earn. Ahead of Australia's national leader is Cyril Ramaphosa, the president of South Africa, who, with an annual salary of $341,802, earns nearly 20 times the average wage in his country. Singapore's Lee Hsien Loong earns over 17 times what the average citizen earns, while India and Russia's leaders earn 11 times their countries' average wage.

Australia's differential between the rate at which its leader is paid and the wage received by the average of its citizens is directly comparable to that of the leaders of Italy, Belgium, Switzerland, the United States, Egypt, Mexico and Japan.

Dissatisfaction with the salary that a political leader or other politicians earn seems to have more to do with the electorate's view of their performance than with the absolute figures involved. The British Taxpayers' Alliance considers British parliamentarians vastly overpaid

; however, the British prime minister, earning $282,716 per annum is paid 4.5 times the average British citizen. This places him 23rd on the list of world leaders ranked by level of remuneration relative to what their countries' citizens earn and directly comparable with the leaders of France, Luxemburg, Iceland, Denmark and Sweden.

; however, the British prime minister, earning $282,716 per annum is paid 4.5 times the average British citizen. This places him 23rd on the list of world leaders ranked by level of remuneration relative to what their countries' citizens earn and directly comparable with the leaders of France, Luxemburg, Iceland, Denmark and Sweden.

Part of the issue in Britain appears to be the lack of confidence the country has in its political leaders (currently exacerbated by the Brexit crisis). It has been argued that there is a large social and economic disconnect between the majority of the British electorate and those who govern them. In a comment published in The Guardian on March 20, 2019, Aditya Chakrabortty noted the substantial difference in background between career politicians and the electorate which has feed a belief that parliamentarians do not appreciate the concerns of those they govern. Chakrabortty wrote, 'Of the MPs elected in 2017...over half had come from backgrounds in politics, law, or business and finance. In fact, more MPs come from finance alone than from social work, the military, engineering and farming put together. That winnowing-out of other trades and ways of life has a direct consequence on our law-making.'

A similar disconnect between electorate and lawmakers appears to be occurring in both the United States and Australia. American political scientists, Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page, analysed 1779 legislative outcomes over a 20-year period and concluded that 'economic elites and organised groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on US government policy, while mass-based interest groups and average citizens have little or no independent influence'.

Similar claims have been made about Australia. Writing in The Monthly in June 2014, the publication's contributing editor Richard Cooke noted, 'As the social base of our political institutions has hollowed out, the train drivers, farmers and small-business owners on the backbenches are dwindling, leaving behind lawyers, businesspeople and union officials. Parliament has always been richer, whiter and more male than most of Australia; now it belongs almost exclusively to a different class as well.'

It is this sense of a political class acting either against or without reference to the wishes of those they govern that goes a long way toward accounting for the resentment almost uniformly felt toward what Parliamentarians are paid. There is a prevailing sense that they are not doing their job and that they are remote from the average citizen. The dwindling support for the two major parties in Australia, a country which has compulsory voting, is proof of the growing sense of disconnection between politicians and those they claim to seek to represent.