Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Further implications

Further implications

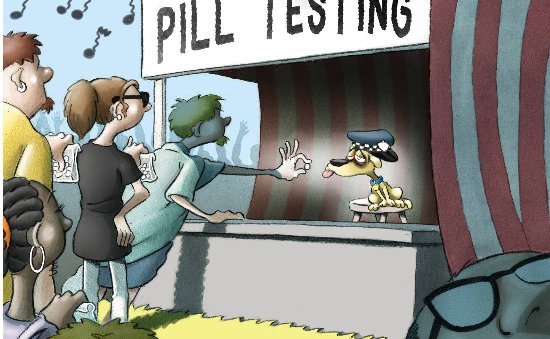

The debate surrounding pill testing is an example of the persistent tension between the two conflicting positions of harm minimisation and prohibition that feature in Australia's policies for dealing with the sale and use of illegal drugs.

In the case of pill testing, the arguments of those opposed to the measure seem to rest substantially on a misrepresentation of the advantages that testing offers. Critics complain that pill testing does not supply any guarantee that the substances that are being tested will be safe to ingest. However, those conducting pill tests do not claim that their tests will ever indicate that a substance is safe to consume. In Australia's only sanctioned pill test trial, conducted in the Australian Capital Territory in April, 2018, participants having their drugs tested had to sign a waiver indicating that they were aware that whatever results the tests gave would be no guarantee that the substances were safe and that the testers bore no liability if the drugs caused harm.

Pill testing is quite literally a harm minimisation procedure. It seeks not to remove harm but to reduce it. Thus the tests are intended to warn of some of the hazards the substances being tested may present. These tests can never indicate that any drug will be completely harmless. As critics have noted, deaths are not only caused by contaminants in the drugs, deaths are often caused by the prohibited substances themselves. There is wide variability, for example, in the manner in which individuals react to drugs such as MDMA (the primary ingredient in ecstasy). What may be a harmless dose or concentration for one individual may prove toxic to another.

What seems vital in this debate is that exaggerated claims not be made by either side. Some proponents of pill testing, especially parents whose children have died after ingesting an illegal drug, have called for the measure in ways which suggest it would have prevented their son or daughter's death. One such mother has declared her belief that testing may have saved her son's life. She has stated, 'My son would have never, ever wanted to come out of that festival in a body bag. I think that if there was something available, it's a safety net.'

Such arguments are very misleading. If pill testing is regarded as a safety net it has to be accepted that it is one that is full of holes. It will save some young drug users from the adverse effects of some substances but not from those of others. It is not a guarantee.

Such arguments are very misleading. If pill testing is regarded as a safety net it has to be accepted that it is one that is full of holes. It will save some young drug users from the adverse effects of some substances but not from those of others. It is not a guarantee.It is also important that pill testing's possible benefits not be ignored because some of its opponents present arguments that are no longer valid. The criticisms made by toxicologist Andrew Leibie of the unreliability of onsite pill testing technologies used a music festivals have been used out of context.

Leibie's criticisms do not automatically apply to all testing methods used at festivals.

Leibie's criticisms do not automatically apply to all testing methods used at festivals. A background information document produced by the Library of the Autralian Parliament said of Leibie's claims 'It should be noted that in his critique Leibie focuses on the limitations of colourimetric tests and other on-site test kits, in comparison to laboratory testing. However, these limitations are well documented, and, according to Dr Monica Barratt, a researcher with NDARC, acknowledged by most pill testing services. Barratt argues that pill testing services only use such kits as their main tool when they don't have access to better technology. Fully-funded pill testing services typically use proper laboratory equipment, as was the case at the Groovin the Moo festival.'

It would appear that partial truths have been presented on both sides of this debate. Proper policy decisions will not be made unless there is careful consideration of accurate data.