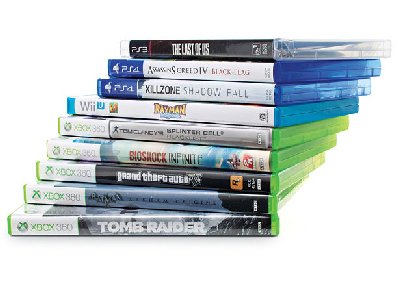

Right: Game companies' dilemma: the increasing complexity of video games has led to much higher development costs. Game makers point to in-game purchases as a way to keep prices for the basic games low.

Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Arguments against banning loot boxes

Arguments against banning loot boxes

1. Loot boxes enable game makers to hold down the up-front price of games

Those who support loot boxes argue that they have acted as a means of keeping the cost of games relatively low. The argument is put that as the level of development needed to produce games has grown dramatically over the last two decades so have the costs of production. It is claimed that game makers would have needed to increase the sale price of games significantly to recoup their outlay and make a profit.

In the event, it appears that game prices have remained relatively unchanged. Kyle Orland, in an article published in Ars Technica on October 7, 2020, noted, 'Adjusting for inflation, we can see the actual (2020 dollar) value of top-end disc-based games plateaued right around $70 for almost a decade through in the '00s and early10s.'

It has been claimed that in-game purchases such as loot boxes have enabled game developers to keep the upfront cost of games relatively low. This point was made in the BBC's Newsbeat segment on September 12, 2019, which stated, 'As games developers have to pour more and more money into creating more innovative and impressive titles, game prices haven't really gone up dramatically.

So, they try to make their money back in other ways - which is why in-game purchases have become so big.'

Joel Hruska, explaining the proliferation of loot boxes in an article published in Extreme Tech on October 13, 2017, stated, 'Part of the problem is that game prices have been stuck at $59.99 for well over a decade. If pricing had simply kept pace with inflation, games should be sitting at ~$71. If a game were to sell 3 million copies, that's ~$35 million in revenue that won't be earned.'

Some commentators have suggested that loot boxes and similar in-game profit-generating devices are inevitable as consumers would resist the point-of-sale price increases that would have to be charged for games otherwise. In an article published by CNBC, on September 29, 2020, Bartosz Skwarczek, CEO and co-founder of video game reselling marketplace G2A, stated that increasing the price of AAA games 'risks jeopardizing gaming for a new generation of young gamers.' He warned that higher prices, coupled with the economic fallout of the coronavirus pandemic, may prevent cash-strapped consumers from buying expensive new titles.

The article's author, Ryan Browne, noted, 'Nine in 10 gamers believe a new video game should cost less than $60, according to a survey undertaken for G2A by research firm Censuswide. The study, which surveyed 1,031 Americans in August [2020], found all respondents think a price of more than $60 is too much for a single game, while 59 percent say gaming has become too expensive.'

Defenders of loot boxes urge players to see them as a form of subscription that extends the pleasure of the game once the initial outlay has been paid. Steve Boxer, writing in April 2017 for the Games Central column published in Metro noted, 'For games publishers microtransactions essentially amount to a form of subscription. Once players get sufficiently deep into a game and discover that they need to splash out on microtransactions to properly compete they start paying for microtransactions on a regular basis, bringing in small but frequent payments that are tantamount to subscriptions - with all the cashflow benefits those bring to the publisher.' The implication is that for game producers microtransactions are merely a more palatable way to have the consumer pay for the game.

Matthew McCaffrey, 34, an assistant professor at the University of Manchester has written a paper on the challenges regulating micro-transactions in video games. McCaffrey states, 'It's a question of how to increase the revenue that can be generated through games without infuriating your customers. So, that's the challenge.'

2. Loot boxes add to player enjoyment

The manufacturers of video games claim that a major reason for including loot boxes in their products is to improve the player experience.

Referring specifically to the chance element which exists because players generally do not know exactly what will be found within the loot boxes they purchase, Kerry Hopkins, a vice president of EA (Electronic Arts) Games, has compared them with other forms of game that offer the consumer a pleasurable surprise.

Hopkins has stated, 'If you go to-I don't know what your version of Target is-a store that sells a lot of toys and you do a search for surprise toys, you will find that this is something people enjoy. They enjoy surprises. It is something that has been part of toys for years, whether it is Kinder eggs or Hatchimals or LOL Surprise!. We think the way we have implemented those kinds of mechanics-and FIFA, of course, is our big one, our FIFA Ultimate Team and our packs-is quite ethical and quite fun; it is enjoyable to people.'

EA argue that the interaction between skill and the chance element that derives from purchased packs is one of the features of video games that make them enjoyable.

Kerry Hopkins explained, 'The surprise that we talked about a little before-are fun for people. They enjoy it. They like earning the packs, opening the packs, and building and trading the teams. The thing about FIFA Ultimate Team is that it is not any one of those things-the points, the coins, the packs, the items, the trading market or building your team-but an integrated, really well-designed mode in a game that we launched 11 years ago. Arguably, I guess it is one of the most popular game modes in the world. All those pieces go together; they are very balanced; they go together and players love playing them.'

Another EA executive, Shaun Campbell, has explained the pleasure that comes from earning or purchasing extension packs or loot boxes and claims they are an essential part of the fun that games offer.

Campbell has stated, 'From a player's perspective, that ability to get the pack-one of the bundles of items with the players' kit and so on in the game-is one of the most important features to them. When you look at what Ultimate Team is, it is about being able to build your best virtual team. The ability to do that is about earning the FUT coins to do it. Taking that mechanic out essentially prevents one of the most appealing things for players about the game: "I want to have my perfect team, which I can then play against another-my best friend's team, or another competitor's." It is a key feature of the game that players enjoy. From the perspective of a lot of people, it has been the driver. Look at the Ultimate Team: we've had it in the game for over 10 years, and it continues to increase in popularity. But it is about that ability to build your team.'

Kat Bailey, the editor of US Gamer, has examined the popularity of loot boxes and similar microtransactions. In October 2017, she wrote, 'While Star Trek Online was pushing lock boxes, FIFA and Madden were introducing Ultimate Team for the first time-a mode in which you built fantasy teams by ripping card packs to obtain players of varying degrees of rarity. Madden Ultimate Team and FIFA Ultimate Team proved wildly popular, almost single-handedly transforming sports gaming...'

Giving an overview of the phenomenon, of which she is not personally a fan, Bailey writes, 'Loot boxes, CCGs, Ultimate Team, and gacha-driven mobile games like Fire Emblem Heroes all have their differences and their quirks, but they're all driven by the simple pleasure of opening a mystery box and getting something good. They could be an epic costume; a new character, or in the case of Middle-earth: Shadow of War, a really great orc. Whatever it may be, people love it.'

3. Loot boxes are not gambling

Defenders of loot boxes claim they are not gambling.

So far as many game producers and regulators are concerned, loot boxes are not part of a game of chance because, although a player may not win the particular object s/he is seeking, that player will always win something.

The Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB), which rates most video games sold and published in North America, asserts that loot boxes are not gambling because the player is always guaranteed to receive in-game content (even if it something he or she does not want).

From the point of view of pre-existing gambling regulations, there is another reason why loot boxes are not regarded as gambling. The principal reason offered for loot boxes not to be considered gambling is that they are not games of chance which offer the player the opportunity to win either cash or an item that has an independent monetary value.

This distinction centres on the difference between an activity in which items without a direct monetary value can be won as a secondar element of the game and an activity where the sole purpose of the game is to win money through the operation of chance. The difference was spelt out by Rune Kristian Lundedal Nielsen and Pawel Grabarczyk in a paper published by the Digital Games Research Association in June 2019. (Digital Games Research Association (DiGRA) is a nonprofit international learned society whose work focuses on game studies and associated activities.)

The authors stated, 'We believe that games of chance played for money and games of skill played without financial stakes are indeed very different from each other.'

In most jurisdictions, while loot boxes involve an element of chance because players do not know what they will get, they are not covered by existing gambling legislation because the items 'won' are not considered to have monetary value.

This is the current position in Britain. In 2017, the UK Gambling Commission published a position paper on 'virtual currencies, esports and social casino gaming'. In that paper, it states that virtual items (like those won in loot boxes) are 'prizes'. The paper further states, 'Where prizes are successfully restricted for use solely within the game, such in-game features would not be licensable gambling.'

A similar position pertained within the Netherlands in 2017. Rami Ismail, a spokesperson for the Dutch independent games maker, Vlambeer's, has stated, 'My legal understanding is that for loot boxes to be gambling, there should be a chance of something of objective value to be returned. Loot boxes always return a digital item of subjective value, whereas the objective value is zero - this being a binary file.'

This is also the position which is currently adopted in Australia. According to the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA), the body responsible for

overseeing the federal Interactive Gambling Act, loot boxes do not constitute gambling under Australian law. ACMA stated that "In general, online video games, including games that involve 'loot box' features, have not been regarded as 'gambling services' under the Interactive Gambling Act 2001, because they are not 'played for money or anything else of value'. That is, the game is not played with the object of winning money or other valuable items". Queensland's Office of Liquor & Gaming Regulation and even New Zealand's Department for Internal Affairs are of the same view, and the NSW Law Reform Commission have shared similar thoughts in the past.

4. Regulation can address the potential problems associated with loot boxes

Defenders of loot boxes claim that there is no need to ban them as any potential harm can be prevented by regulation.

It is claimed that potential abuse of loot boxes is already largely controlled by the games industry's own protocols and practices. The Interactive Games and Entertainment Association (IGEA) has stated, 'The industry has worked hard for years to ensure that loot boxes, and indeed video games as a whole, are a fun and safe experience. As a matter of law and just good practice, the industry is transparent about in-game purchases - ensuring that prices are displayed correctly, descriptions are accurate, and marketplaces are as clear as possible. It is also commonplace for this information to be declared prior to download or

purchase, even if a player has made purchases before. The industry empowers consumers to make informed decisions by providing them with what they need before purchasing any products, including loot boxes.'

All games on the three major platforms - Microsoft, Nintendo and Sony - need to disclose to players how likely it that they will receive a certain item from a loot box, according to a statement by the Entertainment Software Association issued in 2019. The companies plan to implement the policy by the end of 2020.

IGEA has also stressed that the games industry has been careful to protect children from inappropriate experiences by making it possible for parents to control their children's games. IGEA has stated, 'video game consoles, PC platforms and mobile game stores offer robust controls that enable parents and carers to decide what games children can play according to age rating, how long they can play for and, importantly for loot boxes, who is authorised to shop in a game's digital store and make purchases.

It is even possible to set spending limits for children. These innovative technological tools help parents and carers tailor the online experience of children so that it is age appropriate and ensure that children are not able to spend money on loot boxes or other products without obtaining permission first. The industry will also frequently encourage parents and carers, through social media and instructional videos, to show an interest in the games played by children and talk to them about responsible video gaming and purchasing.'

Many defenders of loot boxes argue that self-regulation, within the games industry, is the best approach. This claim is made in part because the laws currently being drawn on to control loot boxes relate to the regulation of gambling and it is difficult, if not impossible, to reasonably apply them to the microtransactions that take place within games.

This point has been made by Daniel Cermak, in a treatise published in the Michigan State International Law Review in 2019. Cermak stated, 'Though there could be a case to be made that state gambling statutes need a major overhaul to bring them into the twenty-first century, particularly with online gambling,291 the court system is not the best way to regulate the devices for parties on either side of the loot box debate...The best practice for loot box regulation is self-regulation. This self-regulation, as seen in Japan... The self-regulation of Japan's standard gacha games, largely comparable to loot box mechanics, could serve as a [model]... Publishing the odds of receiving certain items, setting monthly spending limits and a self-regulated ban on certain loot box mechanics that requires multiple combinations of loot box wins are all methods seen in Japan that could provide useful protection for consumers while protecting the practice for game developers.'

Other commentators have argued that self-regulation alone is insufficient and that it should be bolstered by a legal framework requiring game manufacturers to adhere to certain standards.

In August 2019, Leon Y. Xiao of the University of London argued, 'The level of consumer protection provided by game companies often depends on the legal regulation in place, which is why it is necessary for legal regulation to set a minimum acceptable standard to ensure a sufficient degree of consumer protection, in the absence of proactive voluntary self-regulation.'

Xiao further argued, 'The best solution going forward with loot box regulation may be for the law to set a minimum standard that does not overregulate, and for self-regulation to complement the legal regime by striving to achieve an even higher standard of consumer protection.' In detail he proposed, 'The combined regulatory approach would ensure that loot boxes whose rewards are worth real-world money cannot be sold to children...and that their sale to adults will be strictly scrutinised (and taxed) as gambling by regulators.'

5. A ban on loot boxes would be difficult to enforce

Supporters of loot boxes argue that a ban would be government overreach, would be actively opposed by many players and so would be very difficult to enforce.

In an opinion piece published in Forbes in June 2019, senior contributor, Erik Kain, suggested that such a ban was an unreasonable infringement of players' rights to enjoy their games as they wish. He stated, 'I'm wary of government involvement here. If Blizzard wants to sell me loot boxes so I can get Overwatch skins, and I want to buy them, we should have the right to make that transaction, do-gooder politicians be damned.'

Kain further notes that a ban seems an over-reaction relative to the harm loot boxes are likely to cause. 'Banning gambling might seem like a good idea, but people get around these bans easily enough. And loot boxes are, in the end, a very mild sort of gambling-gambling, to be sure, but not the same as horse races or slot machines, endless money pits with nothing on the other side but despair.'

Other commentators have suggested the negative impact a ban on loot boxes could have. On October 15, 2019, on Casino Org, Brooke Keaton commented, 'Banning a feature that can be problematic for some is not always the best answer - it can often have the effect of making it more attractive and pushing it underground. And there are already reports of a "black market" where gamers trade or sell on their loot box spoils, with gaming companies oft accused of being slow to clamp down on this.'

The above concern (that a total ban on loot boxes, prohibiting their inclusion in games for players of all ages, would prove difficult to enforce) highlights the problems that could occur with a ban that targeted only young players. Currently, there is draft legislation in the United States which would, if approved, prohibit the sale of loot boxes in games targeted at children under the age of 18. Games marketed toward wider audiences could also face penalties from regulators like the Federal Trade Commission if companies knowingly allow children to purchase these randomized crates.

However, critics have noted that a ban targeting only products sold to minors would be even harder to enforce. Games are widely shared among player communities and it would be virtually impossible to ensure that games containing loot boxes did not end up in the hands of players under 18.

A Newsbeat report published by BBC News on September 12, 2019, notes, 'Enforcing a ban on loot boxes for under-18s might prove difficult for the government, given consoles and online accounts can be easily shared by many people.'

There is the additional concern that were loot boxes to be banned from games targeting minors, there would be no requirement for games producers to warn young players of the risks associated with them