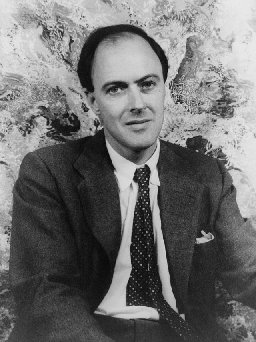

Right: Roald Dahl charmed generations of children with his wild and funny characters.

Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Arguments against altering classic children's books

1. Many of the changes made to classic children's books are unnecessary and damagingThose who oppose changes being made to classic children's stories argue that these alterations are often unnecessary, poorly done and damage the stories being modified. They claim the language that is substituted lacks interest and clarity. They further claim that the overall meaning of the stories is being changed.

Critics claim that many of the alterations made to classic children's stories are simply unnecessary, making changes to preserve an unrealistic standard of politeness. For example, it has recently been revealed that Enid Blyton's 'Famous Five' series has been edited to remove words and phrases such as 'shut up' and 'don't be an idiot.'

2GB radio host Ben Fordham condemned such changes as foolish and excessive. Fordham has stated, 'Do they seriously think that young readers are going to be harmed by words like "idiot"?'

2GB radio host Ben Fordham condemned such changes as foolish and excessive. Fordham has stated, 'Do they seriously think that young readers are going to be harmed by words like "idiot"?'

Children's author Andy Griffiths has also defended Blyton's word choices, arguing, 'They are fairly harmless words, they are used by kids and adults in everyday life and they belong in her books...'

Some of the recent modifications made to Roald Dahl's stories have been cited as examples of alterations that destroy the sense and attractiveness of the stories. In 'Fantastic Mr. Fox', the line 'each man will have a gun and a flashlight' has been amended to, 'each person will have a person and a flashlight.' In 'The Witches', the grandmother's advice that 'you can't go around pulling the hair of every lady you meet' is removed and replaced with, 'there are plenty of...reasons why women might wear wigs and there is certainly nothing wrong with that.'

Critics claim that such alterations do not reproduce the sense of the original text and are virtually meaningless. Indeed, it has been argued that these changes are likely to make young readers reluctant to read the stories. Kat Rosenfield, a novelist and cultural critic, has stated, 'They're going to change the language of [Dahl's] books in a way that is quite substantial and really has stripped [away] quite a lot of the magic and the cheekiness in the way that he saw the world that was so resonant to kids..."

Critics claim that such alterations do not reproduce the sense of the original text and are virtually meaningless. Indeed, it has been argued that these changes are likely to make young readers reluctant to read the stories. Kat Rosenfield, a novelist and cultural critic, has stated, 'They're going to change the language of [Dahl's] books in a way that is quite substantial and really has stripped [away] quite a lot of the magic and the cheekiness in the way that he saw the world that was so resonant to kids..."  Laura Hackett, deputy literary editor of London's Sunday Times newspaper, has also objected to the poor quality of the edits made to Dahl's work. She has stated, 'The editors at Puffin should be ashamed of the botched surgery they've carried out on some of the finest children's literature in Britain...I'll be carefully stowing away my old, original copies of Dahl's stories, so that one day my children can enjoy them...'

Laura Hackett, deputy literary editor of London's Sunday Times newspaper, has also objected to the poor quality of the edits made to Dahl's work. She has stated, 'The editors at Puffin should be ashamed of the botched surgery they've carried out on some of the finest children's literature in Britain...I'll be carefully stowing away my old, original copies of Dahl's stories, so that one day my children can enjoy them...'

It has further been claimed that in addition to destroying meaning and appeal at key points in a story, alterations like these can change the nature of the whole text. There is concern that the integrity and central purpose of the books will be lost. PEN America, a community of 7,500 writers that advocates for freedom of expression, said it was 'alarmed' by reports of the changes to Dahl's books. Suzanne Nossel, the chief executive of PEN America, has stated that one of the problems with re-editing works was that 'by setting out to remove any reference that might cause offence you dilute the power of storytelling.'

Critics fear that the more changes that are made to a text, the further it moves away from what its author intended. Nossel warns, 'The problem with taking license to re-edit classic works is that there is no limiting principle...You start out wanting to replace a word here and a word there and end up inserting entirely new ideas.'

Critics fear that the more changes that are made to a text, the further it moves away from what its author intended. Nossel warns, 'The problem with taking license to re-edit classic works is that there is no limiting principle...You start out wanting to replace a word here and a word there and end up inserting entirely new ideas.'  Nossel has further noted, 'If we start down the path of trying to correct for perceived slights instead of allowing readers to receive and react to books as written, we risk distorting the work of great authors and clouding the essential lens that literature offers on society.'

Nossel has further noted, 'If we start down the path of trying to correct for perceived slights instead of allowing readers to receive and react to books as written, we risk distorting the work of great authors and clouding the essential lens that literature offers on society.'

2. Classic children's books are altered for commercial reasons

Opponents of altering classic children's books claim that many of these alterations are made to ensure that books will continue to be sold. They argue that the publishers are not primarily concerned about maintaining an author's legacy or keeping their books alive in the modern world. Rather publishers and distributers are concerned to keep these books contributing to companies' profits.

Currently, there is a substantial movement in the children's publishing industry to have titles which promote inclusion and diversity. Michelle Smith, a senior lecturer in literary studies at Monash University, has noted, 'Within children's and young adult literature in the past five or 10 years, there's been a huge push towards books being more diverse and a lot of this pressure has come from young readers themselves on social media.'

Smith claims that the owners of the copyrights of authors such as Dahl are concerned that this developing preference for children's books that feature acceptance of cultural, social, and ethnic diversity may diminish the profits they can expect to gain from some of their traditional best sellers. Smith states, 'If they are dealing with works that are signed up in multimillion-dollar deals for adaptation, then of course they are keen to ensure that the Dahl brand is not damaged.'

Smith claims that the owners of the copyrights of authors such as Dahl are concerned that this developing preference for children's books that feature acceptance of cultural, social, and ethnic diversity may diminish the profits they can expect to gain from some of their traditional best sellers. Smith states, 'If they are dealing with works that are signed up in multimillion-dollar deals for adaptation, then of course they are keen to ensure that the Dahl brand is not damaged.'  Laura Marsh, the literary editor of the New Republic, has similarly stated, 'What they're doing is morally censorious, but they're doing it in the name of preserving a cash cow of intellectual property across as many platforms as possible for as long a time as possible until they no longer own that intellectual property.'

Laura Marsh, the literary editor of the New Republic, has similarly stated, 'What they're doing is morally censorious, but they're doing it in the name of preserving a cash cow of intellectual property across as many platforms as possible for as long a time as possible until they no longer own that intellectual property.'

It is claimed that publishers are concerned that some of their older titles may cease to be bought by parents and teachers. Smith has explained, 'Publishers are aware that controversial topics, such as sex and gender identity, may see books excluded from libraries and school curriculums, or targeted for protest. Librarians and teachers may select, or refuse to select, books because of the potential for complaint, or because of their own political beliefs.

To retain their sales, publishers will make revisions in the hope of keeping traditional titles popular. Children's book author Rebecca Lim has stated, 'This may sound cynical, but if the cash cow is still giving, the novels are then looked at every few years to make sure there's nothing in them that will offend the children of today.'

To retain their sales, publishers will make revisions in the hope of keeping traditional titles popular. Children's book author Rebecca Lim has stated, 'This may sound cynical, but if the cash cow is still giving, the novels are then looked at every few years to make sure there's nothing in them that will offend the children of today.'

Critics claim that publishers should be concerned to preserve the works of their traditional authors, as originally written, not rewrite them so that they more closely coincide with current preferences. They argue that these texts should be respected and kept unaltered, not repackaged for profit. Matthew Walther, editor of The Lamp, a Catholic literary journal, and a contributing opinion writer for the New York Times, has stated, 'I, for one, do not believe that philistines should be allowed to buy up authors' estates and convert their works into "Star Wars"-style franchises...In a saner world there would be a sense of curatorial responsibility for these things. "Owning" works of literature, insofar as it should be possible at all, should be comparable to a museum's ownership of a Caravaggio. Clarify and contextualize, promote and even profit - but do not treat art like you would your controlling interest in a snack foods consortium.

Anston Cameron, an Australian author and occasional columnist for The Age, has similarly stated, 'Owners of [the copyrights of] literary works should be custodians, not co-authors. Sadly, it's a custodianship ever more skewed by capitalism, in which today redesigns yesterday so as to sell it to tomorrow.

Anston Cameron, an Australian author and occasional columnist for The Age, has similarly stated, 'Owners of [the copyrights of] literary works should be custodians, not co-authors. Sadly, it's a custodianship ever more skewed by capitalism, in which today redesigns yesterday so as to sell it to tomorrow.

3. Children should read current books for contemporary views and language

Those who oppose alterations being made to classic children's texts claim that instead publishers should be doing more to promote new authors. To expose children to contemporary views and attitudes, these critics argue that new books should be published which present modern outlooks and viewpoints.

It has been claimed that in Australia very little of the already limited publishing market is available to contemporary Australian authors. The Australian market is still very small in comparison to the rest of the English-speaking publishing world and is largely dictated to by trends in North America and Britain. Rebecca Lim, an Australian writer, illustrator, and editor has claimed that there is little room made on commercial bookshelves for Australian authors and that publishers prefer traditional, established authors whose work they believe will be easier to sell. Lim has stated, 'People who are emerging, First Nations [authors], [people] living with disability or LGBTQI, people who are migrants or refugees, if there is a perceived "less saleable" voice, or more time is needed to bring those voices to market, publishers will not largely take a risk on them.'

Lim has further claimed that by restricting access to less conventional authors, Australian publishers are risking alienating many young readers who do not see themselves or their world reflected in the books that are being published. She has stated, 'We've got to de-colonialise the way we think about publishing, selling and writing books in this country. We need to take more "risks" ... or we will lose readers who don't see books as being for or about them to other media.'

Lim has further claimed that by restricting access to less conventional authors, Australian publishers are risking alienating many young readers who do not see themselves or their world reflected in the books that are being published. She has stated, 'We've got to de-colonialise the way we think about publishing, selling and writing books in this country. We need to take more "risks" ... or we will lose readers who don't see books as being for or about them to other media.'

Critics claim that in Australia and elsewhere a disproportionate amount of publishing effort is put into reproducing the works of established authors whose books inevitably reflect a limited and dated worldview. It has further been noted that publisher preferences are reflected in the preferences of teachers and others who determine what books are made available to children. In 2021, Edith Cowan University conducted a study of the children's book preferences of 82 trainee teachers at the university. It found the trainee teachers preferred older books published during their own childhood or earlier. Only 4.5 percent of the 177 books listed portrayed people of colour; while the top 10 books - nominated by at least a third of the trainee teachers - were all at least 25 years old at the time of the survey. Dr Helen Adam, the lead researcher involved in the study, noted that the teacher-selected texts were 'all fantastic, wonderful books, but there is no representation of diversity in those books and the stories are reflecting last century. If that's all teachers and parents are choosing, then we are denying today's children the chance to see their lives and their worlds reflected in children's books.'

It has been claimed that contemporary authors are able to positively reflect Australia's modern social, ethnic, and cultural diversity and so build acceptance, allowing all children to feel included. Dr Helen Adam, a senior lecturer at Edith Cowan University has indicated that she would like to see a focus on contemporary Australian authors such as Maxine Beneba-Clarke [an Australian author Afro-Caribbean descent], Indigenous author Jasmine Seymour, young adult writer Ambelin Kwaymullina, Scott Stuart, whose books such as "My Shadow is Pink" explore gender identity, and AFL football player Nic Naitanui [who is of Fijian descent]. Dr Adam has stated, 'The Australian children's picture book industry is amazing - we have got the most talented writers. If we can hear the voices of those that are different to ourselves in our stories that's how we become a more inclusive and just society.' Adam acknowledges the value of classic texts and believes they should remain unaltered; however, she believes far more emphasis should be placed on contemporary stories for children. She has stated, 'Leave the classic writers alone, their books are classic for a reason. But if we're giving the platform to this talk about the importance of children's books, we need to shift it to the importance of today's books for today's children.'

Wendy Rapee, chair of the Children's Book Council of Australia (CBCA), has similarly claimed that young people want books that allow them to read about their current world with all its diversity, complexity and challenge. She has noted that the titles featured on the CBCA's just-released Notables list for 2023 reflect contemporary issues including the environment, mental health, family and its complexity. Rapee has stated, 'Those sorts of things are showing up now in the writing for young people today, so that they recognise themselves, and they're becoming more empathetic.'

Wendy Rapee, chair of the Children's Book Council of Australia (CBCA), has similarly claimed that young people want books that allow them to read about their current world with all its diversity, complexity and challenge. She has noted that the titles featured on the CBCA's just-released Notables list for 2023 reflect contemporary issues including the environment, mental health, family and its complexity. Rapee has stated, 'Those sorts of things are showing up now in the writing for young people today, so that they recognise themselves, and they're becoming more empathetic.'

4. Classic children's texts should be discussed with young readers, not censored

Those who argue against altering classic children's books claim that these revisions tamper with the past. They assert that such alterations rob children of an opportunity to read about values and behaviours that are no longer acceptable and to discuss why these attitudes are now rejected. Critics of these revisions argue that parents and teachers should be willing to use classic texts as an opportunity to educate children against the prejudices that existed in earlier times and are still encountered today.

Supporters of unrevised classic children's books argue that they allow children to see that people in earlier times spoke and behaved differently. These books can also show what some people in the past believed. Anita Bensoussan, the Administrator of the Enid Blyton Society, has explained, '. It's a good thing for children to understand that society alters over time, so I think it's important to keep the focus on the originals [of Blyton's books]."

A similar point has been made by Stephanie Bunbury, an Australian journalist living in London who writes on culture for the Melbourne Age and the Sydney Morning Herald. Bunbury has stated, 'Why shouldn't young children be allowed to understand that people used to speak differently and, indeed, think differently? There is nothing so wonderfully precious about Blyton's language that demands its preservation intact, apart from the fact that it exists. It is what it is.

A similar point has been made by Stephanie Bunbury, an Australian journalist living in London who writes on culture for the Melbourne Age and the Sydney Morning Herald. Bunbury has stated, 'Why shouldn't young children be allowed to understand that people used to speak differently and, indeed, think differently? There is nothing so wonderfully precious about Blyton's language that demands its preservation intact, apart from the fact that it exists. It is what it is. Relatedly, Jeff Cieslikowski, writing for FIRE (the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education) has argued, 'Those who strive to impose the norms of today on the art of yesterday might contemplate this quote from novelist L.P. Hartley: "The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there" ... Dahl's books are products of their time, and we should treat them as such.' Cieslikowski has also quoted the chief executive officer of FIRE, Greg Lukianoff, who has claimed that reading texts written in the past 'can lead to a deepening of your appreciation of the world and how even your historical norms will look quaint and strange to your children'.

Relatedly, Jeff Cieslikowski, writing for FIRE (the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education) has argued, 'Those who strive to impose the norms of today on the art of yesterday might contemplate this quote from novelist L.P. Hartley: "The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there" ... Dahl's books are products of their time, and we should treat them as such.' Cieslikowski has also quoted the chief executive officer of FIRE, Greg Lukianoff, who has claimed that reading texts written in the past 'can lead to a deepening of your appreciation of the world and how even your historical norms will look quaint and strange to your children'.

Michelle Smith, Senior Lecturer in Literary Studies at Monash University has stressed the role that adults should play in having discussions with children about problematic values in classic books. Smith notes that these original texts allow 'discussion of topics such as racism and sexism with parents and educators, more easily achieved if the original language remains intact.' She concludes, 'Although many aspects of the fictional past do not accord with the ideal version of the world we might wish to present to children, as adults we can help them to navigate that history, rather than hoping we can rewrite it.'

Natalie Otten, President of the Australian School Library Association, has noted there is a big debate on how to teach context around controversial titles without offending. She has stressed the important role that parents and teachers are able to play. Otten explains, 'Considering the context of the time in which the material was first published can support learners to think about the content and its relevance in today's world. Rather than "banning" books that are outdated, they can be used as rich conversation tools with learners to highlight different perspectives and thinking over time.'

Natalie Otten, President of the Australian School Library Association, has noted there is a big debate on how to teach context around controversial titles without offending. She has stressed the important role that parents and teachers are able to play. Otten explains, 'Considering the context of the time in which the material was first published can support learners to think about the content and its relevance in today's world. Rather than "banning" books that are outdated, they can be used as rich conversation tools with learners to highlight different perspectives and thinking over time.'

Some commentators note that removing books that express views we no longer agree with will not remove prejudiced or cruel behaviour. Children are likely to encounter these attitudes and actions in the real world and may imitate them. Books can be a corrective for such hurtful and intolerant behaviour. Classic texts that contain some problematic views and values are a safe and useful learning occasion, allowing parents and teachers an opportunity to discuss what attitudes and behaviours are considered appropriate today. Jessie Tu, an author and commentator writing for Women's Agenda, has observed, 'Correcting children's books won't stop children from enacting or perpetrating racist or discriminatory behaviour. If we censor [offensive] words ... from old texts, then we bar ourselves from having important conversations about language and hinder our ability to explain to future generations why we wouldn't use words like that today.'

5. Changes should not be made to the work of an author without his or her agreement

Critics of changes made to classic children's texts claim that such changes are illegitimate where the authors are dead and unable to give their consent.

It has now become common for books to be reviewed prior to publication by 'sensitivity readers'. The readers work to ensure that texts do not give unnecessary offense, particularly to cultural or racial groups to which the author does not belong. This contemporary practice is conducted with the authors' knowledge and changes are only recommendations that authors can reject.

However, many critics oppose 'sensitivity readers' being used on traditional children's classics, whose authors are deceased. These critics argue that any changes made may well be contrary to what the author would have wanted. Kat Rosenfield, a novelist, and cultural critic who has written about the increasing use of sensitivity readers, has argued that Dahl's work should not be altered as his death means he is unable to provide input. Rosenfield argues that without any involvement from Dahl, 'There's an element of fraudulence to it.'

However, many critics oppose 'sensitivity readers' being used on traditional children's classics, whose authors are deceased. These critics argue that any changes made may well be contrary to what the author would have wanted. Kat Rosenfield, a novelist, and cultural critic who has written about the increasing use of sensitivity readers, has argued that Dahl's work should not be altered as his death means he is unable to provide input. Rosenfield argues that without any involvement from Dahl, 'There's an element of fraudulence to it.'  American journalist and editor, Maria Bustillos, has similarly stated, 'I am a fan of this kind of work [sensitivity readings], in principle. But sensitivity readings are for new books; they are a step in the editing process... The distinction between messing with the past, and improving on the present, is a critical one...' Because Dahl is no longer alive to contribute to and approve any alterations to his work, Bustillos advises, 'Republish Roald Dahl as he wrote, or don't publish him at all.'

American journalist and editor, Maria Bustillos, has similarly stated, 'I am a fan of this kind of work [sensitivity readings], in principle. But sensitivity readings are for new books; they are a step in the editing process... The distinction between messing with the past, and improving on the present, is a critical one...' Because Dahl is no longer alive to contribute to and approve any alterations to his work, Bustillos advises, 'Republish Roald Dahl as he wrote, or don't publish him at all.'

It has been claimed that in the case of Roald Dahl there is substantial reason to believe that he would not have approved of his work being altered. Matthew Dennison, author of a Dahl biography, has noted that the author had difficult relationships with his editors and disliked having his work revised. Dennison has commented that Dahl often deliberately focused on individual words or expressions and 'continued to use elements of the interwar slang of his childhood, and aspects of his vocabulary up to his death.' Dennison has also stated that Dahl objected to alterations to his work which he believed reflected adult sensibilities rather than children's preferences. Dennison has quoted Dahl observing, 'I never get any protests from children. All you get are giggles of mirth and squirms of delight. I know what children like.'

Dahl felt strongly that his vivid language and exaggerated characters were central to his stories' appeal to children. He stated, during a 1988 interview, 'I find that the only way to make my characters really interesting to children is to exaggerate all their good or bad qualities. If a person is nasty or bad or cruel, you make them very nasty, very bad, very cruel. ... That, I think, is fun and makes an impact.'

Dahl felt strongly that his vivid language and exaggerated characters were central to his stories' appeal to children. He stated, during a 1988 interview, 'I find that the only way to make my characters really interesting to children is to exaggerate all their good or bad qualities. If a person is nasty or bad or cruel, you make them very nasty, very bad, very cruel. ... That, I think, is fun and makes an impact.'  Dahl was also recorded expressing objections to alterations being made to his work after his death. In a 1982 conversation with the artist Francis Bacon, Dahl stated, 'I've warned my publishers that if they later on so much as change a single comma in one of my books, they will never see another word from me. Never! Ever!'

Dahl was also recorded expressing objections to alterations being made to his work after his death. In a 1982 conversation with the artist Francis Bacon, Dahl stated, 'I've warned my publishers that if they later on so much as change a single comma in one of my books, they will never see another word from me. Never! Ever!'  Though the remark was made with humour, commentators have noted that it accurately reflects Dahl's dislike of having his work altered.

Though the remark was made with humour, commentators have noted that it accurately reflects Dahl's dislike of having his work altered.

Critics have also suggested that children's author Enid Blyton would have been reluctant to have her work revised. Nadia Cohen, author of the biography 'The Real Enid Blyton', has stated, 'She would be horrified at things being edited or taken out of her books because of fear of causing offence. She would have thought of that as ludicrous and would have roared with laughter. Her view would have been, "If you don't like my books, don't read them.'" Cohen noted that Blyton was never concerned about the opinion of adult critics. She has observed that when even at the height of her fame, some libraries banned Blyton's books because of their perceived lack of literary merit, Blyton replied that she did not care about the opinion of anyone over 12.

Others have also noted Blyton's disregard for those who criticised or sought to alter her work. Jacqueline Wilson, who has recently written what has been described as a sequel to 'The Magic Faraway Tree' is aware that Blyton did not readily accept suggested alterations to her work. Wilson has speculated about Blyton's response to the new book, stating, 'I'm not sure that she would be that thrilled.'

Others have also noted Blyton's disregard for those who criticised or sought to alter her work. Jacqueline Wilson, who has recently written what has been described as a sequel to 'The Magic Faraway Tree' is aware that Blyton did not readily accept suggested alterations to her work. Wilson has speculated about Blyton's response to the new book, stating, 'I'm not sure that she would be that thrilled.'