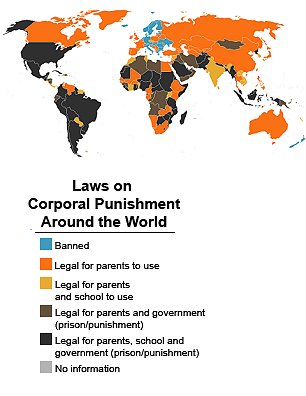

Right: parental discipline involving physical punisment: its legality around the world

Right: parental discipline involving physical punisment: its legality around the world

Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Arguments in favour of making smacking illegal

Arguments in favour of making smacking illegal

1. Smacking easily escalates into more serious physical abuse

It has been claimed that when parents believe it is appropriate for them to physically punish their children it can be difficult for them to draw a line short of inflicting serious injury and in some cases death.

Associate Professor Susan Moloney, the President of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians' paediatrics and child health division has claimed that physical punishment could escalate to abuse.

Professor Moloney has stated, 'We know that a significant number of child homicides are a result of physical punishment which went wrong," she said. "It started off as physical punishment and went too far.'

Opponents of parents using corporal punishment claim that much child abuse begins with spanking: a parent accustomed to using corporal punishment may, on this view, find it all too easy, when frustrated, to step over the line into physical abuse. One study found that 40% of 111 mothers were worried that they could possibly hurt their children. It is argued that frustrated parents turn to spanking when attempting to discipline their child, and then get carried away (given the arguable continuum between spanking and hitting). This "continuum" argument also raises the question of whether a spank can be "too hard" and how (if at all) this can be defined in practical terms. This in turn leads to the question whether parents who spank their children 'too hard' are crossing the line and beginning to abuse them.

Opponents also argue that a further problem with the use of corporal punishment is that, if punishments are to maintain their efficacy, the amount of force required may have to be increased over successive punishments. This has been claimed by the American Academy of Paediatrics, which has asserted, 'The only way to maintain the initial effect of spanking is to systematically increase the intensity with which it is delivered, which can quickly escalate into abuse.' Additionally, the Academy noted that, 'Parents who spank their children are more likely to use other unacceptable forms of corporal punishment.'

A 2008 study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine found that mothers who reported spanking their children were more likely (6% vs. 2%) to also report using forms of punishment considered abusive to the researchers "such as beating, burning, kicking, hitting with an object somewhere other than the buttocks, or shaking a child less than 2 years old" than mothers who did not report spanking, and increases in the frequency of spanking were statistically correlated with increased odds of abuse.

2. Parental smacking of children can cause serious psychological damage.

It has been argued that parents smacking their children can result in psycho-emotional harm. Research shows that such punishment can lead to depression, anxiety and substance abuse.

Research published in the American Academy of Paediatrics journal Paediatrics in 2012 based on data gathered from adults in the United States which excluded subjects who had suffered abuse showed an association between harsh corporal punishment by parents and increased risk of a wide range of mental illness.

Associate Professor Susan Moloney, the President of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians' paediatrics and child health division has noted, 'As a paediatrician, what I am most concerned about is the serious long-term effects of physical punishment on children's well-being. This is not about parenting styles or punishing parents, it's about protecting children.

Research shows that a child who experiences physical punishment is more likely to develop increased aggressive behaviour and mental health problems as a child and as an adult.'

3. It is not legal to physically punish children in schools or other institutional settings

Associate Professor Susan Moloney, the President of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians' paediatrics and child health division has noted, 'Australian states and territories have banned physical punishment in both government and non-government schools and the physical punishment of children in juvenile detention centres, foster care and childcare is also now prohibited.'

Susan Moloney also argues children should have the same protection from assault as other members of the community. The Associate Professor has stated, 'If you hit your dog, you could be arrested but it's legal to hit your child.' It has also been noted that physical abuse is not legal when applied to anyone other than one's own children.

This has been condemned as inequitable in that it denies children rights that are allowed to all others.

On October 7, 2011, in The Conversation, Bronwyn Naylor, Director, Equity and Diversity at Monash University and Bernadette Saunders, Senior Lecturer, Social Work at Monash University wrote, 'In Australia the only category of victims who can lawfully be assaulted is children, by their parents. There is no defence for a boss, a teacher or a childcare worker. There is no defence for a husband - domestic violence is now named and criminalised.'

On February 12, 2012, a similar point was made in a Canberra Times editorial, 'We have made rape in marriage illegal. We have abolished hanging and whipping in the criminal justice system. We have abolished corporal punishment in schools. Yet today in Australia it is still legal for parents to physically assault their children - provided it fits the woolly criteria of being "reasonable chastisement" or "reasonable correction".

4. Other jurisdictions have made it illegal for parents to smack their children

There are 33 countries that prohibit the physical punishment of children by their parents. Among them are South Sudan, Germany, Venezuela and New Zealand, the latter of which changed its law in 2007.

In 1979, Sweden became the first country to ban all forms of "corporal punishment". Before the ban, more than half its population considered physical punishment necessary as a disciplinary measure in raising children; however, a significantly smaller percentage now considers it acceptable. According to RACP research, this shift in public attitudes reflects a trend that exists in all countries where domestic corporal punishment has been banned.

Since the change of the law in New Zealand, there has been a fall in the number of people who believe physical punishment is effective and acceptable. Last year 63 per cent of parents surveyed said that, since the law changed, they never, or only rarely, smack their children.

5. Smacking teaches children that force is a solution to problems

It has been claimed that physically punishing children encourages them to become aggressive and teaches the social lesson that physical violence and intimidation are solutions to inter-personal problems.

A 1996 study by Straus suggested that children who receive corporal punishment are more likely to be angry as adults, use spanking as a form of discipline, approve of striking a spouse, and experience marital discord. According to Cohen's 1996 study, older children who receive corporal punishment may resort to more physical aggression, substance abuse, crime and violence.

Critics note that sanctioning smacking is inconsistent as it appears to endorse behaviours that our society claims to disparage. An editorial published in The Age on July 29, 2013, stated, 'When a big child hits a small child in the playground, we call him a bully; five years later he punches a woman for her handbag and is called a mugger; later still, when he slugs a workmate who insults him, he is called a troublemaker; but when he becomes a father and hits his tiresome, disobedient or disrespectful child, we call him a disciplinarian.''

6. Smacking children is not the most effective way to gain their compliance

The Royal Australasian College of Physicians has claimed that physical punishment, besides being hurtful and psychologically harmful, does not always stop bad behaviour. The College claims that there are other, more effective forms of discipline that parents could and should deploy with their children.

Associate Professor Susan Moloney, the President of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians' paediatrics and child health division has noted, 'Children do need discipline to learn appropriate and socially-acceptable behaviour as they grow and develop. But it's increasingly clear that physical punishment is not an effective long-term strategy, because it doesn't work.'

Although smacking may seem effective in the short term, experts claim it is ineffective as a long-term disciplinary measure, with 'adverse consequences' for children's health and wellbeing. They argue it 'works against' its objective (normally obedience) because it fails to achieve long-term behavioural change, causes children to become fearful and mistrustful of their parents and reinforces the message that violence is the way to resolve conflict.

Some researchers believe that corporal punishment fails to work over time because children will not voluntarily obey an adult they do not trust. Elizabeth Gershoff, in a 2002 meta-analytic study that combined 60 years of research on corporal punishment, found that the only positive outcome of corporal punishment was immediate compliance; however, corporal punishment was associated with less long-term compliance.

The Australian Psychological Society holds that physical punishment of children should not be used as it has very limited capacity to deter unwanted behaviour, does not teach alternative desirable behaviour, often promotes further undesirable behaviours such as defiance and attachment to "delinquent" peer groups, and encourages an acceptance of aggression and violence as acceptable responses to conflicts and problems.

Experts say parents need a plan of action for disciplining their children, including some well-thought-out strategies. For example: providing proper supervision; setting suitable, age-appropriate boundaries; using a firm voice; removing children or distracting them from tricky situations; using time-out strategies; withdrawing privileges; and finding ways to explain the meaning of consequences. Rewarding positive behaviour is also considered important in demonstrating parental expectations.