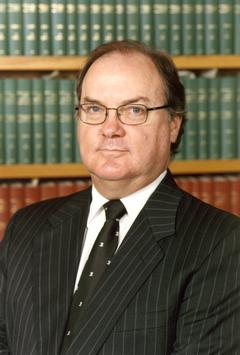

Right: Justice Patrick Keane, a former Queensland Solicitor-General, is one of those who argue that Australia does not need a Bill of Rights. Judge Keane is quoted as saying, 'Australians haven't done too badly with our small brown bird of a Constitution.'

Right: Justice Patrick Keane, a former Queensland Solicitor-General, is one of those who argue that Australia does not need a Bill of Rights. Judge Keane is quoted as saying, 'Australians haven't done too badly with our small brown bird of a Constitution.'Arguments against a federal charter of rights

1. Australian's rights are already sufficiently well-guaranteed.

It has been claimed that the rights of Australians are already well guaranteed by the combined operation of our Constitution, our common law, our parliamentary-generated laws and our courts system. It is claimed all of these interact to ensure the rights of Australian citizens.

It has been asserted that the protection of our rights can be left to our parliamentary representatives and that to legislate for a Bill of Rights would distort our system of government by giving unelected judges too much influence.

There is a long-standing and strong commitment to the rule of law in Australia. Traditional arguments against a Bill of Rights have been that Australia can rely on our proud background of respect for civil liberties and the democratic freedoms of the individual citizen.

Justice Keane, a former solicitor-general, noted that many Australians 'have urged the adoption of our own bill of rights and consider the absence a cause for regret.' Yet Justice Keane further noted, 'Our framers (of the Constitution) were not indifferent to the rights of individuals; they were, however, content to entrust those rights to a legislature composed of citizens.'

Justice Keane has also commented, 'Australians haven't done too badly with our small brown bird of a Constitution.' As evidence of this, Keane cited the handling of abortion and gun control through parliaments.

There are many who argue that Australia's successful democracy removes the need for a bill or charter of rights. As one email correspondent to The Australian on April 26, 2008, stated, 'As far as I can see, we have got by without one [a charter of rights] for the last 220 years and managed to make our way as a democracy pretty successfully.'

2. A charter of rights could upset the balance of our democracy

There is concern that a charter of rights can take power from the federal Parliament and transfer it to the courts and therefore the judges. This is seen as undesirable as politicians are elected whereas judges are not. Thus, it is claimed, politicians can be held accountable for their actions in a way that is not possible with judges

Dr Mirko Bagaric, a lawyer and author, has argued, 'Who do you want to make decisions on the core moral issues that define us as a society?

There are only two choices: politicians or judges. At the moment all of the big decisions in Australia are made by politicians.

A bill of rights transfers much of this power to judges, who are among the least adept people in the community to make decisions on matters of cardinal social importance.

When it comes to giving power to people to make decisions, the most important consideration is accountability.

And that's why we should never hand over things that are vital to us to judges.

They are the only group in the community that (effectively) can't get sacked or disciplined for incompetence or negligence.'

The Australian's editorial of April 12, 2008, stated, 'The constitutional structure of this country is based on the assumption that politicians should resolve political issues, and judges should resolve legal disputes. Recent history tells us that this is exactly how the community would like things to remain.'

A similar point has been made by former New South Wales premier, Bob Carr. Carr has stated, 'A bill of rights, or a charter, will lay out abstractions like the right to life, or privacy, or property, and thus enable judges to determine - after deliciously drawn-out litigation - what these mean.

A shift in power from elected parliaments to unelected judges, by a process of "judicial creep", is part of the bill of rights package.'

Bob Carr has further stated, 'It's my argument that reaching the right balance is an issue for the realm of parliament, shaped by the give-and-take of elections and freedom of the press, not for a realm of judicial policy-making.

Alexis de Tocqueville, the great observer of American politics, taught that democracy arises from the ethos of a people. In Australia that ethos encompasses the parliament, the common law tradition and a free press. Wrenching more decisions out of this realm and planting them with a non-elected judiciary is no advance.'

3. A charter of rights would be expensive

It has been claimed that a charter of human rights would be expensive given the amount of litigation it could generate. It has also been suggested that a charter of human rights would also be expensive to operate as it would be administratively more expensive.

In response to the Victorian Charter of Human Rights, Charles Francis AM, QC, RFD, has stated, 'An examination of the Consultation Committee's Report makes it apparent that the administration of the Charter will be both complex and expensive and will require the employment of a number of additional public servants to carry out all the duties entailed in the function of the Charter.'

Jay Fitzgerald, in an emailed response to the issue of a human rights charter, has stated, 'Anyone seeking to witness the impact of a charter of rights on our Westminster model parliamentary system in Australia should study its effects on Canada. An unmitigated disaster, and for Canadian taxpayers, a very expensive one.'

Doug Parrington, writing in The Gold Coast Bulletin on April 12, 2008, argued that the added capacity to have compensation paid to those whose human rights are found to have been violated will add to the expense of a charter. Mr Parrington stated, 'It is undoubtedly taxpayers who individually stand to gain a lot but collectively will cop it in the neck [if a charter of rights is put in place].

There is no more vulnerable creature in the world than a taxpayer who is financially responsible for all the tragedies amazingly discovered by lawyers.

Politicians, despite all their flaws, at least recognise the point at which taxpayers begin to squeal and don't particularly like laws that allow open season on taxpayers' money.

Judges, on the other hand, simply apply the laws as a matter of principle; whatever compensation is paid is a matter for the state.'

4. A charter of rights could be limited to the wealthy or be exploited by those who are not entitled to the rights they claim

It has been claimed that the manner in which some defence lawyers have sought to use the provisions of Victoria's new Charter of Human Rights is an indication of the way in which a federal charter of human rights might be similarly misused.

Senior prosecutors and lawyers in Victoria have warned of a large number of applications by notorious criminals (including drug boss Tony Mokbel) attempting to use Victoria's Charter of Human Rights to delay or abort their trials.

The charter is dividing Melbourne's legal community, with some arguing it is unnecessary and that defence lawyers' use of it will clog up the courts.

One prosecutor, who declined to be named, has claimed in a report made by The Age that the charter was 'an absolute disaster' for the court system and would clog it up for no good reason.

The same man also claimed that the traditional system of common law had adequately protected Victorians' human rights for decades, and the charter's authors were 'frankly not bright enough' to make it watertight.

The feared consequences of any new charter are that it will see dangerous criminals released into the community on the basis of technicalities created by such a charter.

The Victorian charter has been cited by judges in three cases to support their decision to release defendants on bail. The most recent case was when a man who was accused of belonging to Tony Mokbel's alleged drug cartel was released on bail after magistrate Peter Couzens said the charter, and the higher courts, made it clear defendants were entitled to have their cases heard without delay. The court heard the accused was unlikely to face trial until well into 2010.

It has also been claimed that a charter of human rights may advantage only the wealthy. The experience in other jurisdictions, particularly Canada, has been claimed to demonstrate that a bill of rights, rather than preserving and enhancing the rights of the people most in need of further rights protection, might in fact have the opposite effect and benefit those least in need. Prohibitive legal costs associated with enforcing one's rights under a bill of rights (whether constitutional or statutory) might effectively see the utility of a bill of rights being restricted to wealthy and corporate citizens.

5. A charter of rights could lead to a dramatic increase in time-consuming litigation

It has been suggested that a charter of rights will add an additional layer of complication and legal interpretation to many cases brought before the courts. It has further been suggested that the result of this will be a significant increase in the time that it takes for cases to proceed through the courts.

Referring to the current Victorian situation, Melbourne Law School Associate Professor Jeremy Gans has stated, 'I think people are right to worry about the [Victorian] charter bringing more complex legal arguments to the courts and, in the meantime, a lot of uncertainty, delay and confusion. And the blame for that is the text of the charter itself, which has a lot of ambiguity.'

There is also significant concern that time-delays may actually reduce the rights of some citizens as their cases will take far longer to process. It is also noted that such effects are cumulative with each individual delay having a negative impact on all the cases that come after, an impact which compounds the longer it is allowed to go on.

6. Rights charters are inflexible and can entrench rights that may become inappropriate

It has been claimed that one of the shortcomings of a bill or charter of rights is that each is the product of the time in which it was produced. This means that it may promise citizens rights which at a later point become inappropriate.

It has further been noted that once a population has been given a right in a bill or charter it becomes virtually impossible to remove that right, even when it is clearly desirable to do so.

Sam Crosby, the 25-year-old outgoing president of Young Labor, has stated,' Look at the situation in the US, where 200 years ago the founding fathers thought it was a pretty good idea to entrench a right to bear arms. They had just come out of a war of independence with Britain, and I'm sure 200 years ago that was probably a good idea. But ... if the founding fathers were sitting down today in the 21st century, they probably wouldn't include a provision allowing armed militia. And that's ultimately what we would be deciding if we entrench rights today...

You won't be able to take out a right that's been set down in a charter because then you'll be accused of taking away someone's rights. It's a terribly emotive subject and it invokes an emotional response from people. But it needs to be seriously thought through.'