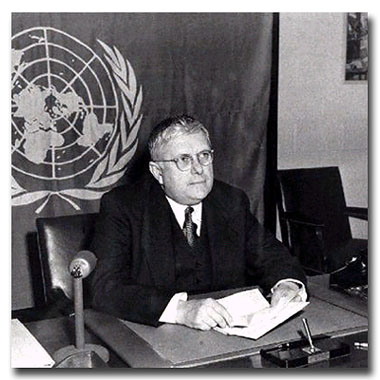

Right: Australian politician Herbert Vere Evatt. In 1948, while Evatt was president of the new United Nations' General Assembly, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was presented to the world as a model for all nations to emulate.

Right: Australian politician Herbert Vere Evatt. In 1948, while Evatt was president of the new United Nations' General Assembly, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was presented to the world as a model for all nations to emulate.

Arguments in favour of a federal charter of rights

1. Australia is the only western democracy without a charter of rights

It has been repeatedly noted that Australia is the only Western democracy that does not allow its citizens the protection of a human rights charter or bill of rights. Great Britain, New Zealand, Canada, the United States of America and South Africa all have Bills of Rights in some form or another.

It has also been noted that Australia's position is particularly anomalous as Australia played a major role in the formulation of an international human rights charter.

On May 23, 2008, Susan Ryan, Chair of the Australian Human Rights Act Campaign, wrote, 'Sixty years ago, when Australia's Foreign Minister Bert Evatt was the first President of the United Nations, and activist Jesse Street was representing us on UN working bodies, the nations of the world made the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The Declaration became the building block of all modern rights instruments, now in effect in all democracies except Australia.

This exception is more than just an anomaly in the history of Australia's proud contribution to international human rights. It constitutes a serious gap in Australia's system of laws and allows much human suffering.'

It has further been noted that two Australian states or territories, Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory, now have human rights charters. Why, critics ask, is it not possible for the Australian federal Government to adopt similar measures?

2. In Australia no single document, including Australia's constitution, enshrines the full rights of its citizens

Australia's constitution does not guarantee the full rights of its citizens. As noted on the Human Rights Act for Australia website, from our constitution we have 'the freedom of religion, freedom from discrimination on the basis of residence, a right to trial by jury, the right to review of government action, acquisition of property on just terms, and some implied rights which have been narrowly defined by the courts.'

An indication of the wide range of areas not explicitly guaranteed by the Australian Constitution is that the Victorian Charter of Human Rights specifies twenty areas where the rights of citizens need to be defined and protected.

Other supposed guarantees of the rights of Australian citizens include legislation passed at federal and state level, most noticeably anti-discrimination legislation, and more recently the ACT Human Rights Act 2004 and the Victorian Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities 2006. While at common law, judges have recognised certain civil liberties.

The Human Rights Act for Australia lobby group argues, 'Together these laws only protect a narrow range of fundamental freedoms of the Australian people. With such a complicated array of laws, it is understandable that Australians are largely unsure of what their rights are or how they can protect them. We are left to blindly trust that those in power have our best interests at heart ...

What we lack is one document, one Act, which clearly sets out the rights of all Australians. A national human rights act would serve this purpose. Alone it is not a panacea to all human rights problems but it has the potential of being an important part of Australian life.'

3. Australia's international treaty obligations have no legal reinforcement within this country

On May 23, 2008, Susan Ryan, Chair of the Australian Human Rights Act Campaign, wrote, 'The Australian Human Rights Act Campaign (New Matilda) ... advocates a human rights act for Australia, based on our existing UN obligations, and operating as an ordinary act of parliament.'

Supporters of such an Act or charter have noted that Australian law has frequently breached our international treaty obligations and that in the absence of national legislation embodying these obligations, Australian law did not prevent their violation, nor require parliamentary scrutiny or accountability in relation to them.

The Human Rights Act for Australia lobby group has claimed, 'Australia has ratified a number of important international covenants including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) ... We have failed to honour our agreement to make these part of our domestic law means that we are in breach of international law.'

The United Nations Human Rights Committee (UNHRC) has found on several occasions that Australia has breached the fundamental human rights of people living in Australia.

Since 1990 the UNHRC has heard almost fifty complaints against Australia. In seventeen of those cases, the UNHRC found that Australia violated ICCPR rights. However, without an Australian Bill of Rights Australian courts cannot hear complaints about human rights violations.

4. Government responses to the threat of terrorism make a charter of rights particularly necessary.

It has been claimed that government responses to the threat of terrorism have seen an unprecedented and excessive attack on the rights and freedoms of Australian citizens. It has further been claimed that these unreasonable erosions of Australian citizens' rights demonstrates the need for a charter.

This position has been put by Ron Dyer, Vice President of the Evatt Foundation, former a member of the NSW Legislative Council between 1979 and 2003 and Minister in the Carr Labor Government from 1995 to 1999.

Mr Dyer has stated, 'I had always held the opinion that parliaments in Australia could be trusted to preserve individual freedoms and not diminish them by enacting draconian legislation.

My confidence in this regard has been eroded, if not destroyed, by recent State and Federal legislation in Australia characterised as "anti-Terrorism laws". It seems to me that these laws go well beyond the proper limits that should apply in a liberal democracy. They certainly call into question my hitherto long-held belief that Australian parliaments could always be relied upon to be a bulwark against encroachment upon our democratic freedoms.

To illustrate my concern, I refer to the Anti-Terrorism Bill (No. 2) 2005 (Commonwealth). This legislation, together with complementary legislation enacted by the Australian States and Territories, contains quite extraordinary preventive detention and policing powers.'

A similar point has been made in September 2007, by the Lord Mayor of Sydney, Clover Moore, who stated, 'Australia is the only democratic nation in the world without a legal human rights instrument. Although human rights atrocities are not common, there is a growing feeling that civil rights are being eroded, particularly in response to anti-terrorism laws and the APEC summit... The threat of terrorism has resulted in the abandonment of a number of fundamental principles in the name of protecting our safety. Without a human rights legal instrument there is no guarantee that other rights will not be traded in the name of security.'

5. There are many disadvantaged groups whose rights could be guaranteed by a federal charter of rights

It has been noted that the rights of disadvantaged groups have been routinely overlooked in Australia and that a charter of human rights would act as a block against unjust treatment of these groups.

On May 23, 2008, Susan Ryan, Chair of the Australian Human Rights Act Campaign, wrote, 'In 2005, under Coalition government policies, small children kept in immigration detention were driven ill and mad by inhuman conditions. Adult asylum seekers lacking documents were condemned to indefinite detention, a decision upheld (with considerable agonising) by the High Court of Australia. Agents of the government, principally its immigration department and outsourced service providers, wrongly deported a seriously ill Australian citizen, Vivien Solon, casting her on the mercies of a church charity in the Philippines. A permanent resident suffering severe mental illness, Cornelia Rau, was detained by the authorities, sent to jail, and then to immigration detention.'

Susan Ryan further noted, 'In our remote indigenous communities, where there are no schools, children cannot exercise a right to education. Devastating violence and horrendous crimes rage in the absence of police support. Seriously ill community members can't get health care, hence the ... seventeen year life expectancy gap with non indigenous Australians. Is it zealotry to raise the issue of these Australians' rights to education, health, and security?'

Supporters of a human rights charter argue that such a charter would make it more difficult to perpetuate such institutionalised injustice.

A survey conducted in 1997 showed that 54% of respondents did not feel that rights were well protected in this country, while 72% supported the introduction of some type of Australian Bill of Rights.7 A majority of Australians appear to be sympathetic to the introduction of a Bill of Rights.

6. A charter of rights need not give undue power to the courts

Supporters of a charter of rights in Australia claim that their aim is not to transfer power from the parliament to the courts. Rather, they argue, they want a charter which will act as a framework within which all government policy and legislation needs to work in order to protect the rights of Australian citizens.

The Human Rights Act for Australia lobby group has claimed, 'When new policies are being developed, human rights principles will be used as [a] framework.

When laws are introduced to parliament, they will be assessed as to whether they are compatible with the human rights act.

When a matter is taken to the courts, the courts will be able to either interpret laws to be consistent with the protected human right, or if this is not possible, to declare a law to be incompatible with human rights.

Importantly, courts will not have the capacity to dismiss or invalidate laws. The final decision on how to deal with the incompatibility will always remain with the parliament.'

As the Human Rights Charter operates in Victoria the following provisions apply. The charter requires that all statutory provisions (for example, laws and regulations) be interpreted, as far as possible, in a way that is compatible with human rights.

Where the court cannot interpret a law consistently with the charter, the Supreme Court may make a Declaration of Inconsistent Interpretation and Parliament will then decide whether to change the law.

Unlike the United States' Bill of Rights, the charter does not allow courts to strike down laws as unconstitutional. In Victoria, the Supreme Court has power only to ask the Parliament to review a law to ensure that it is consistent with citizens' rights. The final decision remains with the Parliament. This is because Parliament is the elected body and therefore considered to be most responsive to the will of the people.