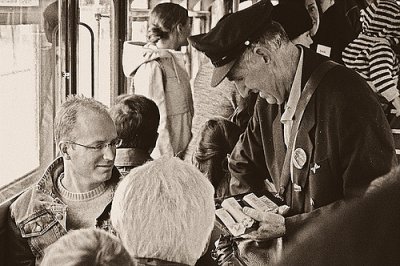

Right: For well over a hundred years, Melbourne's tram conductors were part of the city's scenery, until their demise a few years ago.

Right: For well over a hundred years, Melbourne's tram conductors were part of the city's scenery, until their demise a few years ago.Arguments in favour of reinstating conductors

1. Conductors reduce fare evasionA recent study by RMIT University has found reinstating tram conductors would save millions of dollars lost through fare evasion. An Age editorial of July 15, 2008, stated, 'There is a strong economic case for restoring conductors to a tram system that is beset by fare evasion and a history of faulty ticket systems.'

Referring to claims that automatic ticketing systems are efficient, the editorial stated, '"Efficient" is an odd word to use in describing a system in which more than 10% of tram travellers are fare evaders, if the official estimate of the public transport marketing agency, Metlink, is to be believed. Twelve years ago, when conductors were still a familiar part of tram travel, only 1.7% of passengers were evaders. The actual number now may be much higher than Metlink's figure, and has been as high as 25%. According to RMIT transport economist John Odgers, an estimate of 13.5% is close to the mark.'

In research commissioned for the Sunday The Age: Mr Odgers has argued that restoring conductors to the system would recoup $250 million over the next ten years that otherwise would be lost to fare evasion.

It has further been claimed that the proposed new ticketing system, the myki smartcard, is also shaping up to be financially problematic. These smartcards are now expected to cost $850 million to introduce and $550 million to operate over 10 years.

Critics claim that predictions such as these make the reintroduction of conductors appear a far more cost effective means of preventing fare evasion.

In January 2008 it was estimated that fare evasion across trains, trams and buses in Victoria is now about 10 per cent, meaning 41 million of the 418 million trips taken by passengers in 2007 were free or on discounted tickets.

Enforcement figures show only 159,288 infringement notices were issued to fare evaders, meaning people taking free rides had only a 1 in 258 chance of getting caught.

Greens MP Greg Barber has said that fare evasion rates would not drop until commuters expected to have to show their tickets. 'We've got to get back to staffing the system full time, to make people feel safe, to stop graffiti and to collect revenue,' Mr Barber argued.

2. Conductors provide a variety of services

It has been claimed that conductors traditionally provided a range of services beyond merely selling tickets. The pro conductor site 'Melbourne Tram Conductors: 10th anniversary of Melbourne's last tram conductor' lists the following as some of the functions that trams conductors would perform: carry change to assist people in purchasing tickets from machines onboard trams; provide passengers, including visitors and tourists, with information about the public transport system. Provide passengers with information about Melbourne, such as history, what to see and do, how to get to hospitals, sporting stadiums, the beach etcetera; keep the trams clean and free of graffiti; help people feel safer, by providing a friendly good humoured presence, and calling in security staff where necessary; and provide other assistance as necessary, including helping the elderly and parents with prams.

An Age editorial of July 15, 2008, stated, 'The conductors were dispensed with because the narrowest of definitions of their role made it seem plausible to argue that there was no point in paying people to do what machines could do just as well. But conductors were never just ticket sellers, and the other aspects of their role all had economic consequences, too ... Conductors were also guides to Melbourne, offering free advice to tourists and anyone else who needed help. And, the tram system provided socially useful work for people who may have had no other professional skills, and who thereby became taxpayers and contributors to the local economy themselves.'

3. Conductors may increase the number of passengers

It has been claimed that returning conductors to trams would increase passengers' satisfaction with trams as it would give them a point of human contact which they want. This point has been made in an article written by Chris Berg and titled 'Connies a nostalgic symbol of lost community spirit' which states, 'The apparently widespread desire to return to the days of the connies seems to come ... from a feeling that individuals are being left adrift in an ocean of overly complicated superannuation options, phone plans and credit-card loyalty schemes. Unfriendly businesses are common. On many customer service hotlines, the only way callers can escape the automated system and speak to a live human being is by becoming aggressive and abusive. If anything is damaging our collective psyche, it is probably unresponsive telephone hotlines.' It is argued that a desire for human contact and support in the provision of services is becoming increasingly common and is one of the reasons many want tram conductors reinstated.

An Age editorial of July 15, 2008, stated, 'When people feel safe travelling on public transport they are more likely to use it, and it is difficult to argue that anyone feels safer on trams without conductors than on trams with them.'

Conductors, it is argued, are of particular benefit to tourists unfamiliar with Melbourne's ticketing system. In an online comment published on The Age's Internet site, it was claimed, 'I visited Melbourne for the first time ever last May. I got onto the tram but found I didn't have the right change. I just sat down, had to go where I was going. Next thing I had inspectors handing me a fine, even though I offered to pay them for the ride. Then back in Perth, I received demands for a $150 fine. I wrote in to contest it, but was overruled. I won't be back.'

Stories such as the above have led the supporters of conductors to claim that they would result in larger numbers of satisfied commuters who would be happy to travel by tram again.

4. Other Australian and overseas cities still employ conductors

It has been noted that other Australian tram systems employ conductors.

In South Australia, the 12-kilometre route from Victoria Square, just south of Adelaide, to Glenelg was for fifty years the only part of a former steam railway transit system to survive mass closures in the 1950s.

However increased pressure on public transport, and a growing respect for the convenience of trams when moving through clogged city traffic, has led to an expansion of the trams through the heart of the city and along North Terrace to the University of South Australia's city campus. More expansions are planned.

A $60 million fleet of Flexity trams from Germany has replaced the old H class trams. Conductors have been retained throughout the network and are believed to offer a valuable service and security to tourists and those unfamiliar with the ticketing system and the route.

Sydney's only tram service, MetroRail, is a seven-kilometre light rail from Central to Lilyfield with only seven trams. The network was launched in 1997 with ticket machines.

However, in the lead-up to the 2000 Olympic Games, the 24-hour light-rail system replaced the machines with conductors. 'There were issues with the machines,' Michelle Silberman, a marketing director for the tram network, noted. Ms Silberman claimed, 'Fare evasion with no conductors is always going to be an issue; we are a private company, so to be commercially viable, we needed conductors.'

One of Europe's biggest tram networks has recently revealed it will keep its conductors, despite the imminent introduction of a myki-style ticketing system.

GVB, operators of Amsterdam's 16-line tram network has indicated that conductors would remain after an electronic system replaces paper tickets at the end of 2008. All but three of the system's lines have conductors.

The new Amsterdam ticketing system, a myki-like network in which passengers load chip cards with credit, removes the need for the city's 630 conductors to sell tickets. But a spokeswoman for GVB, Marjolijn van Bilderbeek, has stated that conductors would be kept to maintain the service quality.

5. It would cost relatively little to reinstate conductors

RMIT transport economist John Odgers has produced a report which found that, assuming Melbourne's conductors were paid $48,000 a year, their return would cost the State Government $369 million over the next decade once other costs like superannuation and payroll tax were factored in.

However, the return of conductors would save $250 million lost to fare evasion, equating to a final cost of $119.5 million, or $11.95 million a year. If 1% of Melbourne commuters stopped driving to work and caught a tram instead, benefits from reduced traffic congestion and more tram fare revenue could see the move turn a profit.

The Public Transport Users' Association has provided a slightly different set of calculations to arrive at a not dissimilar figure. The Association estimates that approximately 1,400 passenger-service staff would be required to staff Victoria's 500 trams and 210 stations. Of these 200 are already in the budget (100 conductors and 100 station staff, currently used as ticket inspectors and security guards). This leaves 1,200 to be funded from additional revenue. Allowing $70,000 per employee for salary and on-costs gives a gross cost of $84 million per year to restaff the system.

For comparison, the revised cost to the public of the 'myki' smartcard system is $113 million a year - plus an extra $43 million a year to keep the Metcard system alive while all the bugs in myki are fixed.

Further the Public Transport Users' Association claims there are a number of factors that would cause the net cost to be much less than $84 million.

The Association expects that the annual cost would be between 15 and 20 million, a greater figure than John Odgers' but one that factors in a larger number of staff.