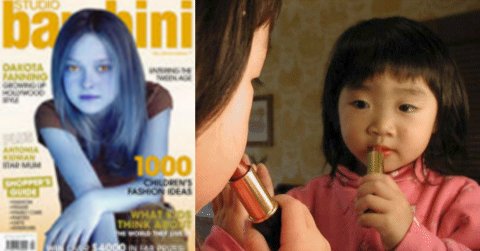

Right: Some commentators argue that media treatment of children often leads preteen girls to the belief that they should aspire to only a limited range of body types and "looks".

Right: Some commentators argue that media treatment of children often leads preteen girls to the belief that they should aspire to only a limited range of body types and "looks".Arguments suggesting that Australia is not doing sufficient to counter the sexualisation of children

1. The sexualisation of children can harm them emotionallyIt has been claimed that the sexualisation of children can psychologically harm young people. It has the capacity to harm the self image of young people and to make them less willing to participate in a range of positive activities, especially sporting activities, which could boost their self esteem. This point has been made in the 2006 report 'Corporate Paedophilia' prepared for the Australia Institute.

The report states, 'Studies have shown that exposure to "appearance-focused

Media" increases body dissatisfaction among children. Apart from contributing to the development of eating disorders, this may have further effects that are not yet fully understood. For example, it is widely recognised that body image concerns are a barrier to teenage girls' participation in sporting activities. It is possible that as younger girls develop higher body dissatisfaction; this barrier may also affect their participation.'

It has also been claimed within this report such sexualisation of children might also encourage premature sexual activity among young people which has the capacity to further damage their self image and divert them from other valuable age-appropriate activities.

The Australia Institute report of 2006 stated, 'Psychologists have also noted that, given that precocious sexual behaviour is an attention-getting strategy used by some older children and young teenagers, the general sexualisation of children may escalate the level of sexual behaviour necessary to attract attention.

It has ... been observed that premature sexualisation can lead to other aspects of child development being neglected; if large amounts of time, money and mental energy are devoted to appearance this will distract from other developmental activities, be they physical, intellectual or artistic.'

Finally, the report states, 'In discussion of the sexualisation of children it is often noted that in developed nations children now reach puberty earlier than they did in the past. For example, Odone cites a UK study of 1,150 eight-year-old children called 'Children of the Nineties' that found that one-sixth of all eight-year-old girls show some signs of puberty, compared to one in100 a generation ago. Also, one in 14 eight-year-old boys have pubic hair, compared with one in 250 a generation ago ... To place these physical changes in context, however, experts in childhood development often note that children's emotional and cognitive development has not advanced at the same pace ... As a result, children's bodies are maturing before they are psychologically mature. Children are thus ill-equipped to deal with sexualising pressure which implies that only a limited range of mature body types are attractive and desirable. An increasing emphasis on a particular body type as the ideal is central to the evidence of sexualisation presented in the previous section.'

2. The sexualisation of children can harm them physically

It has been claimed that the sexualisation of children can result in physical harm to young people. One significant concern is that the images of extremely slim young women promoted to young readers and viewers as an attractive ideal leads to eating disorders, especially in girls. This point has been made in the 2006 report 'Corporate Paedophilia' prepared for the Australia Institute.

The report states, 'Firstly, many studies have linked exposure to the ideal "slim, toned" body type that is considered sexy for adults to the development of eating disorders in older children and teenagers.

There is already some evidence that children in Australia are developing eating disorders at a younger age than previously. Even a "mild" eating disorder can have significant effects on a child's physical health. The idea that increased emphasis on body image for children might be helpful in the context of significant increases in childhood obesity is misguided, since negative motivations stemming from a sense of inadequacy can be very counterproductive. Positive motivations like self-acceptance are more effective in the promotion of healthy living.'

The Australia Institute 2006 report further states, 'Children may be encouraged to initiate sexual behaviour at an earlier The Age: well before they have full knowledge of the potential consequences. Earlier sexual activity in teenagers is linked to a higher incidence of unwanted sex (particularly for teenage girls) and to increasing potential to contract sexually transmitted infections. Both unwanted sex and sexually transmitted infections can have serious long-term consequences.'

Finally the Australia Institute report notes, 'One Australian study found that among 100 girls aged nine to twelve years, exposure to appearance-focussed media ... is indirectly related to body dissatisfaction via conversations about appearance among peers ...

Beyond the effects of highly idealised media images on children's body satisfaction, some child development experts note that as children are exposed to increasingly sexualised popular culture, those children who have 'rebellious, creative or freethinking tendencies' are at particular risk.

They want to be non-conformists, but the symbols of their nonconformity (from skateboard culture to hip hop) become popularized. The more adventurous - and often angrier - kids seek out increasingly outrageous expressions of their rebellion. In media, this often means more graphic violence, more outrageous behaviour, and more explicit sex.'

3. The sexualisation of children can lead to increased instances of paedophilia and child abuse

It has been claimed that sexualising children encourages paedophiles to believe that their behaviour is acceptable and that children are actually ready for and enjoy sexual activities.

This point has been made by Dr Emma Rush. Dr Rush is a researcher at the Australia Institute and the lead author of the report Corporate Paedophilia, published in October 2006 by the Australia Institute. Dr Rush has argued, 'To sexualise children in the way that advertisers do - by dressing, posing, and making up child models in the same ways that sexy adults would be presented - ... implicitly suggests to adults that children are interested in and ready for sex. This is profoundly irresponsible, particularly given that it is known that paedophiles use not only child pornography but also more innocent photos of children.'

Dr Rush further stated, 'Because sex is widely represented in advertising and marketing as something that fascinates and delights adults, the sexualisation of children could play a role in 'grooming' children for paedophiles - preparing children for sexual interaction with older teenagers or adults.

This is of particular concern with respect to the girls' magazines, which actively encourage girls of primary school age to have crushes on adult male celebrities. At the same time, the representation of children as miniature adults playing adult sexual roles sends a message to paedophiles that, contrary to laws and ethical norms, children are sexually available.'

It has also been claimed that such representations of children encourages child abuse. In April 2007 a group of child psychologists sent a letter to The Age in which they stated, 'Marketing to, and media representations of children in age-inappropriate ways send a clear message to the community that this is acceptable, and can contribute to the increasing rates of child abuse. And there is much more to the story.

Perhaps The Age could convene a roundtable of children's professionals and marketers where the facts of life could be explained?'

4. Self-regulation is not sufficient to protect children from sexually explicit advertising and other material

It has been claimed that self-regulation is not sufficient to ensure that children are protected from inappropriate advertising and other material.

Referring to the recent Senate Committee investigating the sexualisation of children, Clive Hamilton, professor of public ethics at Charles Sturt University and former head of the Australian Institute, has stated, 'Instead of proposing even the mildest regulation to help parents control the tide of erotic imagery washing over their children, the Senate committee washed its hands of the problem, declaring it a "community responsibility" and politely suggesting that the advertising industry might think about ways of allaying community concerns. The sexualisation of children has occurred because of the failure of self-regulation, yet the senators' answer is to recommend more."

Dr Hamilton summed up his view in this manner, 'The recommendations of the committee veer from the weak to the pathetic and suggest that the inquiry allowed itself to be snowed by the advertising industry ... The timidity of the recommendations indicates that the committee is happy to invest its faith in the system of self-regulation that has, in fact, brought about the situation that the inquiry was launched to investigate.'

Referring to the same report, Australian Christian Lobby managing director, Jim Wallace, stated, 'Instead of dealing with the need for greater government regulation which gives priority to the interests of children, they have been snowed by the very industry they were inquiring into, effectively leaving the issue in their hands.'

5. Parents need government regulation to help prevent the sexualisation of their children

It has been claimed that it is not reasonable to expect parents to take on the sole responsibility for regulating what their children read and watch and for what their children wear.

This point has been made by Dr Emma Rush. Dr Rush is a researcher at the Australia Institute and the lead author of the report Corporate Paedophilia, published in October 2006 by the Australia Institute. Dr Rush has argued, 'It is unrealistic to expect parents to stop the sexualisation of children by "just saying no" to sexy clothing, children's make-up and so on. As any parent knows, it is not that simple. Peer friendships take on much greater importance in middle childhood and the pressure to conform is keenly felt by children. No parents want their child to be the one left out in the schoolyard.

And no parents want to be put in a position where they must monitor and regulate their children's activities. The sexualisation of children should be tackled at its source: the advertisers and marketers who are seeking to create ever-younger consumers for their products. The burden of remedying the damage caused by sexualising children should not fall on parents, teachers, paediatricians and child psychologists.'

In response to the supposed failure of the Senate Committee into the sexualisation of children, Clive Hamilton, professor of public ethics at Charles Sturt University and former head of the Australian Institute, has stated, 'Instead of proposing even the mildest regulation to help parents control the tide of erotic imagery washing over their children, the Senate committee washed its hands of the problem, declaring it a "community responsibility" and politely suggesting that the advertising industry might think about ways of allaying community concerns. The sexualisation of children has occurred because of the failure of self-regulation, yet the senators' answer is to recommend more.'