.

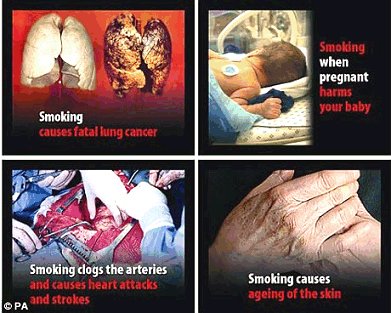

.Right: images of diseases linked to cigarette smoking have been compulsory on packets in some countries for many years.

Arguments against placing a ban on the branding on cigarette packages

1. Such a ban violates international trademark laws

The tobacco industry claims it is heavily reliant upon trademark protection in order to communicate to consumers, and exclude rivals and competitors from the marketplace. For example Philip Morris has 159 trademarks listed on the United States trademark register related to tobacco. British American Tobacco Investments has 113 and Imperial Tobacco has 129.

The industry argues that plain packaging regulations would violate minimum obligations for the protection of intellectual property rights under a number of international trade agreements such as the Trade-Related Aspects of International Property Rights Agreement 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement 1994, and the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property

1883.

Further, the industry argues that because trademarks can only be registered if they are used, they would lose the trademark protection afforded to their logos and symbols. Industry lawyers have insisted that plain packaging would curtail, or even annul, tobacco companies' most valuable assets - trademarks.

In a submission made to the Senate Standing Committee on Community Affairs in 2009, The Institute of Patent and Trade Mark Attorneys of Australia stated, 'The proposed amendments to the Trade Practices Act and the regulations to that Act are of concern to the Institute of Patent and Trade Mark Attorneys because those amendments have a significant impact on trade marks registered under the trade Marks Act as well as the rights of manufacturers, retailers and wholesalers to protect their intellectual property under the Trade Marks Act.'

British American Tobacco (Australia)has stated, ' Plain packaging is essentially a legal, as opposed to a health issue, as it deals with the use of trademarks and a company's right to use their brands.

Attempts to introduce plain packaging into Australia would see BATA take every action necessary to protect its brands and its right to compete as a legitimate commercial business selling a legal product.'

Tim Wilson, an intellectual property expert from the Institute of Public Affairs, has said the government could have to compensate tobacco companies up to $3bn for the loss of intellectual property rights if the measure went ahead.

2. Unbranded packaging will not remove consumer loyalty

It has been claimed that removing conspicuous branding from cigarette packages will not undermine consumer loyalty to particular brands.

Adam Joseph, Readership Director of the Herald Sun and a member of the Australian Marketing Institute's Victoria State Council, has stated, 'Most smokers have a very strong loyalty to their brand of choice. Assuming a smoker's memory is longer than that of a goldfish, there's a very good chance they will still remember the name of the brand of cigarette even without packaging to prompt them at point of sale every day.'

Research indicates that one third of all consumers who do not find their tobacco brand or pack size will walk out of an outlet without purchasing anything. This seems to indicate that brand loyalty is sufficiently strong that smokers will go to another sales outlet in order to be able to purchase the brand they prefer.

3. Cigarette packaging is not intended to attract new smokers

Cigarette companies have claimed that no useful purpose will be served by removing brands from cigarette packages as the purpose of such branding is to enable established smokers to recognise their brand of choice, not to attract new smokers.

The industry denies that packs are a form of advertising. For example, the Tobacco Institute of New Zealand argued 'package stimuli, including the use of trade mark, are of no interest to people not already within the market for that specific product'.

In a review of challenges facing the tobacco industry in January 2010, The Tobacco Reporter noted, 'While the industry has by and large avoided appealing to underage consumers by steering clear of media such as the Internet, youth smoking continues to be a worrying phenomenon. Consumption in the teen segment is on the rise again in the United States, and youth smoking continues to be prevalent in much of the emerging world. In Indonesia, for example, 20 percent of smokers are in the 10-18 age group.' This observation suggests that the tobacco industry genuinely sees youth smoking as a problem and not something that it seeks to encourage.

4. Manufacturers will find other ways to brand

It has been suggested that cigarette manufacturers will find other means of product differentiation if they lose the capacity to distinctively mark the cigarette package.

Adam Joseph, Readership Director of the Herald Sun and a member of the Australian Marketing Institute's Victoria State Council, has stated, 'So if manufacturers can't brand the packaging, then what about the product itself? It's not too hard to imagine that the smoke makers might start to get creative with the actual paper they use to wrap the tobacco. Tradition says cigarette paper should be plain white - but there's no reason it always has to be so.

For instance, what if Marlboro - the scarlet brand - added a thin red stripe to the design of cigarette paper? When lighting up, this would clearly signal to a smoker - and to those around him or her - that they were a Marlboro Man or Marlboro Woman.'

It has also been suggested that cigarette companies might also design and market slip-covers or sleeves that could be put over the plain package and which could carry a brand and a logo. They could also promote branded cigarette cases and perhaps even cigarette holders baring company logos might make a return.

Professor Simon Chapman from the University of Sydney's School of Public Health has indicated his belief that manufacturers would find different ways to differentiate their cigarettes.

Professor Chapman stated, 'There are certainly companies around the world experimenting with different looks, coloured filters and sticks. They could make cigarettes in the shape of joints, for example, or in fluorescent paper.'

5. Removing brands may increase cigarette sales

Cigarette companies have claimed that plain packaging may actually increase smoking, especially among young people. It has been suggested that this may occur because in the absence of branding manufacturers might attempt to attract purchasers to their product by reducing the price. This may increase cigarette consumption, especially among adolescents for whom cost is a significant factor shaping their decision to purchase.

The availability of low budget generic brand cigarettes in the United States has been cited as evidence that plain packaging would be ineffective in reducing demand: the market for these low budget, brandless generics has been seen as demonstrating that smokers would still smoke such

products.

It has further been argued that removing high profile brands will actually encourage the greater manufacture and sale of these cheap generic brands as there will be less to distinguish them from the high profile brands. Such brands, it has been argued, are cheap enough to attract young smokers.

It has also been suggested that no brand packaging may appeal to young people as it would make smoking appear an act of rebellion, something more anti-authoritarian and high risk.

Consumers are less brand-loyal at the low end of the market, and this has facilitated the emergence of new players, such as Richland Express, importing cigarettes, and new brands, such as the Chinese cigarettes imported by Patron Group. These new brands have attracted a consumer base because of their low cost. Stripping the obvious markings from established brands is likely to accelerate trends toward these cheap brands of cigarette.

It has also been argued that the removal of obvious branding from high profile make will encourage counterfeiting and that these counterfeits are likely not to include government health warnings. Imperial Tobacco Australia spokesperson, Cathie Keogh, has stated, 'If the tobacco products are available in the same easy-to-copy plain packaging, it makes it much easier for counterfeiters to increase the volume of illicit trade in Australia, which is currently reported at about 12 per cent of the market. That illicit product won't have or may not have the health warnings on it. It won't be subject to ingredients reporting.'

Finally, it has been suggested that removing brands will have little impact on children's decisions to smoke as studies have shown that children's decisions about smoking are not predominantly determined by brand. A recent English study found, 'Three-quarters of the sample expressed no brand loyalty, but of those who did, taste of the cigarette was the main reason they gave for choosing it, although some made the choice because they considered that cigarette to be less harmful.'