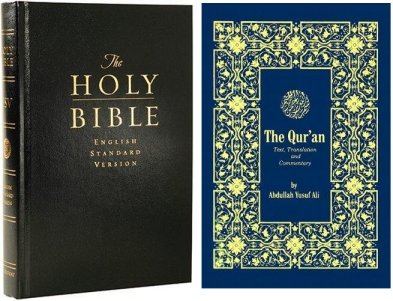

Right: under Victorian legislation, religions other than Christianity may be taught in primary schools, but Access Ministries, the main provider of instructors / teachers, does not cater to these other faiths. Instructors in Islam and other religions are provided by their own organisations.

.

Right: under Victorian legislation, religions other than Christianity may be taught in primary schools, but Access Ministries, the main provider of instructors / teachers, does not cater to these other faiths. Instructors in Islam and other religions are provided by their own organisations.

. Arguments against primary schools running Special Religious Instruction classes

Arguments against primary schools running Special Religious Instruction classes

1. Running only Christian education classes is discriminatory in a pluralist society

It has been argued that it is inappropriate to give religious instruction that focuses exclusively on Christianity. Victoria's is a pluralist society in which there are believers in a large number of religious creeds in addition to those who have no religious belief at all. A pluralist society is one which recognises and values a diversity of beliefs.

Although religious communities such as Buddhists, Jews and Baha'i's also offer religious instruction classes in Victoria, students can only choose to receive instruction from one religious tradition.

More than 90% of the religious instruction currently being given in Victorian government primary schools is delivered by ACCESS Ministries, a Christian multi-denominational group supported by twelve Christian Churches - nominated from these participating churches: the Anglican Church, the Australian Christian Churches (Assemblies of God in Australia), the Baptist Union of Victoria, the Christian Brethren Fellowships in Victoria, the Christian Reformed Churches of Australia, the CRC Churches International, the Churches of Christ in Australia, the Lutheran Church of Australia, the Presbyterian Church of Australia, the Salvation Army, the Uniting Church in Australia and the Wesleyan Methodist Church of Australia.

2. The religious instruction is often not presented neutrally

Complaints have been made the information contained in religious education classes is often not presented in an unbiased manner. It has been claimed that some of the volunteers actually attempt to make converts among the students.

Jewel Topsfield, education editor for The Age, in an opinion piece published in the paper on April 3, 2011, stated, 'Volunteers are not educators. Too many are motivated by the desire to convert students to Christianity rather than teach religion in an impartial way.'

Topsfield further stated, "Proselytising [preaching to attract believers] is supposed to be forbidden in religious education classes, but the accounts of many students suggest it happens. One mother withdrew her children after her six-year-old daughter was taught that families who did not attend church would drown when the second flood came."

Critics claim that such pressure may cause the child psychological distress. The parent of one child informed Topsfield, "[My daughter] begged me to start going to church so we wouldn't die. She was so frightened she had nightmares and her siblings felt the fear too."

3. Many parents object to religious instruction being given in schools

Critics claim that instructing a child in religion is the role of a parent not of the school. Scott Hedges, who is a member of the Fairness in Religions in Schools campaign, a grassroots campaign made-up of concerned parents has stated, 'In my opinion, religion is an intimate part of family life.'

Critics further claim that many parents would prefer that schools refrain from giving religious instruction. The website, Religions in Schools, set up by concerned parents to gather views on the issue, has received many emails. A large number stated that while learning about religion is important, they object to this being done within Victorian primary schools. A poll conducted by The Age resulted in 67% of respondents objecting to religion being taught in Victorian schools.

The education editor for The Age has stated, 'One of the most common explanations of why the government funds private schools is that parents have the right to choose an education for their children in line with their religious beliefs and values. Similarly, many parents choose government schools because they are not religious.'

4. We should have general religious education and ethics taught in schools, not religious instruction

Several recent Australian studies have recognised the central role that education plays in building a socially inclusive and secure multi-faith society.

These studies have recommended a shift from special religious instruction, as it is known in Victoria, currently taught be volunteers from mostly Christian communities in government schools, to a more inclusive form of religions education to be developed and taught by qualified educators. It has been argued that rather than 'teach Christianity', Victorian government primary schools should be encouraging children to respect all religious traditions.

Gary Bouma,UNESCO Chair in Inter-religious and Intercultural Relations - Asia Pacific, and Anna Halafoff, Researcher in Inter-religious and Intercultural Relations at Monash University have stated, 'Allowing narrow religious messages to be taught to young Australians could sustain inter-religious ignorance and heighten social tensions; whereas, promoting an understanding of diverse faiths is likely to increase respect for religions and to minimise alienation and thereby contribute to a more harmonious society.'

A similar point has been made by the Humanist Society of Victoria which argues, 'even in primary school, students would benefit from a professional, non-partisan course of comparative religions and beliefs, under the category of "general religious education". By learning about the tradition, history and geography of the major religions and world-views, they would better understand today's world and their fellows in our multi-ethnic society. Social cohesion and civic trust would improve. Applied ethics would sit well in GRE, even more than in SRI.'

5. Children who opt out of religious instruction classes are not given an alternative activity

A complaint before the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission claims children who opt out of religious classes are being discriminated against because they are denied a proper secular alternative.

Scott Hedges who is a member of the Fairness in Religions in Schools campaign is unhappy about the lack of real opinions given those who opt out religious instruction. Hedges has claimed that when he questioned the religious instruction his children were receiving, 'I was given the generous option of having my daughter "opt out" and sit in the teachers office with the Jew and the atheist child while the majority of her friends stayed with the ministry volunteer and their fun cartoon time. Some choice.'

Another parental story gathered as part of the Humanist Society Of Victoria's campaign against religious instruction in schools includes the following - 'On the first day of the class, my daughter, being the only one whose parents had [opted her out of the SRI class] was asked to sit on her own at her desk, in the same room, while the SRI class was conducted, so she got Christian education by watching it any way... she was in tears at being left out of the group. She just had to sit and watch, and was told by the volunteer, "Your mum ticked no, so you can't participate in this class".

6. From a legal perspective, the Victorian public education system should be secular

Opponents of the manner in which religious instruction is currently being delivered in Victorian government schools argue that it is contrary to the legal basis on which public education was established in this state.

According to this argument such education was intended to be secular, that is, not promoting a particular faith. Critics argue that teaching only Christianity as happens in most Victorian primary schools is contrary to the intent of the legislation that set up the state education system.

The Humanist Society of Victoria claims to have recently obtained reputable legal advice that the current departmental administration is inconsistent with the secular intent of the Education & Training Reform Act 2006 and appears to infringe equal opportunity law. The Society is gathering evidence to support a formal legal challenge to the manner in which religious instruction is delivered in Victoria.

Scott Hedges is part of the Fairness in Religions in Schools campaign, a campaign made-up of concerned parents. Mr Hedges has stated, 'Australians, including Australian Christians, should care about the legacy of "secular" education and the importance of such education in a pluralist democratic society.' Mr Hedges also argues that the current mode of religious instruction in Victorian schools is contrary to the spirit in which secular instruction was first legally established here.