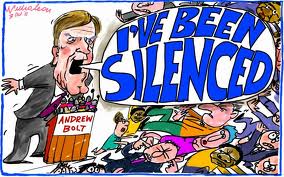

Right: How cartoonist Nicholson saw Andrew Bolt's conviction.

Right: How cartoonist Nicholson saw Andrew Bolt's conviction.

Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Arguments against retaining section 18C of Australia's Racial Discrimination Act

Arguments against retaining section 18C of Australia's Racial Discrimination Act

1. Freedom of speech is a vital element of the democratic process

Freedom of speech is a fundamental human right. It is one of the thirty human rights outlined in the United Nation's Universal Declaration of Human Rights, issued in 1948, to which Australia was an initial signatory. Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states, 'Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.'

This right has been seen as necessary to intellectual growth for both individuals and societies. It has been held as the key component of social, economic and political debate. Freedom of speech is seen as a fundamental component of democracy as an informed electorate is necessary if people are to vote effectively. Censorship (the imposition of limits and bans on what people are able to say) has been condemned as a major threat to intellectual and political freedom.

It has been stated that freedom of expression has to apply to those with unpopular or disputed views, as much as to those with views that are generally endorsed or accepted. An editorial published in The Australian on March 4, 2014, stated, 'The concept of free speech has been grounded in Enlightenment principles for more than 300 years. It covers not only those with whom we agree, but those with whom we disagree, often vehemently.'

The Herald Sun editorial of March 12, 2014, defends this tradition. 'Australians pride themselves for saying what they think, fairly and without fear or favour. You might not like what I say but I defend my right to say it.'

The editorial further states, 'Gagging people from fairly and legitimately held opinions is censorship. It is a basic denial of freedom of speech.'

Similarly, Attorney-General, George Brandis, has stated, 'It is not the role of government to tell people what they are allowed to think and it is not the role of government to tell people what opinions they are allowed to express.'

2. The capacity to give offence is not a sufficient basis for limiting free speech

It has been claimed that the threshold at which the current 18C provisions of the Racial Discrimination Act begin to operate is too low. According to this argument, too little has to be done by a supposed perpetrator before that person's freedom of speech is removed under the current law.

There are two levels of objection to the prohibition of utterances on the basis that they are 'offensive'.

Firstly, there are those who argue that the mere giving of offence, even if that offence should be extreme, is not sufficient grounds for limiting freedom of speech. According to this line of argument, wounded feelings are not of sufficient consequence to justify a legal limitation being placed on freedom of expression. The Prime Minister, Tony Abbott, has stated in parliament 'Sometimes...free speech will be speech which upsets people, which offends people'. The Attorney General, George Brandis, has further stated, 'People have the right to say things that other people would find insulting, offensive or bigoted.'

Prohibiting comment on the basis that it may give offence could serve to limit legitimate public debate. The key case frequently used to indicate where such restrictions have already occurred is the successful legal action taken against Herald Sun columnist Andrew Bolt for remarks made about pale-skinned Aborigines. In an editorial published on March 4, 2013, The Australian stated, 'In 2011, the Federal Court ruled that News Limited columnist Andrew Bolt's commentary about light-skinned Aborigines seeking advantage based on their heritage amounted to unlawful racial vilification. The court found Bolt guilty because the complainants were likely to have been "offended, insulted, humiliated or intimidated". However provocative Bolt's words, causing offence is not vilification.'

The second basis on which offensiveness has been challenged as a reason for limiting freedom of speech is that the determination of what constitutes offensiveness is far too subjective. Public affairs commentator and blogger Ken Parish has stated in relation to legal formulations such as 'likely to offend', '[The] assessment by individual judges and administrators of subjective, value-laden concepts determines controversies not the application of reasonably precise and knowable legal standards.'

According to Parish and others 'offensiveness' is too subjective a term to be applied with any precision and the result is that virtually any utterance with some perceived racial connection could be deemed insulting by someone. Critics claim that making judgements on the basis of offensiveness causes far too many restrictions being imposed on freedom of expression.

3. There is a variety of laws to protect against serious consequences of 'hate speech'

It has been noted that there are already laws that prohibit any incitement to violence, including that based on racial discrimination.

The Commonwealth Criminal Code makes unlawful statements urging the use of force or violence against a person or group distinguished by their race, religion, nationality, national or ethnic origin or political opinion. This is an offence punishable by imprisonment for up to seven years if the use of force or violence would threaten the peace, order and good government of the commonwealth, and otherwise by imprisonment for up to five years.

It has also been noted that not all the provisions of section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act are to be amended. It will remain unlawful to express racially-based opinions intended to intimidate. Attorney General, Senator George Brandis, has also proposed that there be an extension of the Racial Discrimination Act to outlaw racial vilification.

4. Section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act has not succeeded in preventing racism

It has been claimed that legal prohibitions are not an effective means of preventing racist acts, racist comments and the racist attitudes which prompt them.

University of Queensland, Garrick professor of law, James Allan, has claimed that section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act has not been effective in preventing racist outbursts. Professor Allan has stated, 'The idea that this little law is going to do anything is garbage, to be totally honest.'

As evidence of the law's ineffectiveness, critics have noted that the Executive Council of Australian Jewry's annual report on anti-Semitism listed 657 reports of racist violence directed at individuals or Jewish facilities in 2013 to September. The figure marked a 21 per cent increase on the previous year.

Similarly, in 2010-11 there were 422 complaints made about racist behaviour under the act. That figure rose to 477 the following year, and to 500 last year. Critics have claimed that if the section 18C of the Anti Discrimination Act were having an effect these figures would be declining rather than increasing. They claim that such growth indicates that prohibitive laws are not the best means of preventing racist comments.

It has been claimed that attempts to counter racism by restricting freedom of speech have also been ineffective in other jurisdictions. In an opinion piece published in The Australian on March 29, 2014, Gabriel Sassoon stated, 'Europeans have a long tradition of banning hate speech, but racism, anti-Semitism and anti-Muslim abuse are at fever pitch on the Continent. French Jews have been leaving the country in ever-increasing numbers. For all France's paternalistic hate-speech laws, its Jews live under threat and so do other minorities.'

5. Offensive comments are better countered with argument than prohibition

It has been claimed that racist and other offensive comments are better countered by debate and education rather than law and prohibition.

This point was made by Bill Rowlings in an article published in The Punch on September 29, 2013. Mr Rowlings has stated, 'The answer to speech or words permeated wholly or partly by hate or stupidity is more free speech, not less. People who are maligned should be able to speak out or to write, in the same forum and in others forums to a similar length, to highlight the wrong-thinking that lies behind the typical Bolt-like misinformation, misogyny or ignorance about miscegenation.'

It has further been suggested that all prohibiting the expression of racism ideas does is drive these ideas underground. They are still held; they are simply not in a position to be challenged. Thus, Bill Rowlings has further stated, 'Free speech allows fools and bigots...to out themselves and put objectionable views in the public space where they can be appropriately debated, rebutted and/or ignored.' Bill Rowlings has argued that what is needed is not prohibition but a guaranteed right of reply. Rowlings has claimed, 'The issue should be about how we force the media to give equal time and weight to outraged responses, not whose lawyer has the bigger wig.'

An editorial published in The Australian on March 6, 2014, similarly stated, 'Over time, strictures on free speech merely drive racism underground where it becomes more dangerous, away from public scrutiny. Free speech serves the interests of all, especially those at risk of racism.'

In the same vein, Gabriel Sassoon, a former public affairs director for Advancing Human Rights, has stated, 'Australians have a right to express any view they choose to. They have the right to be bigots if they so choose. And we have the right to ridicule them mercilessly. That is the essence of free speech.'