Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Further implications

Further implications

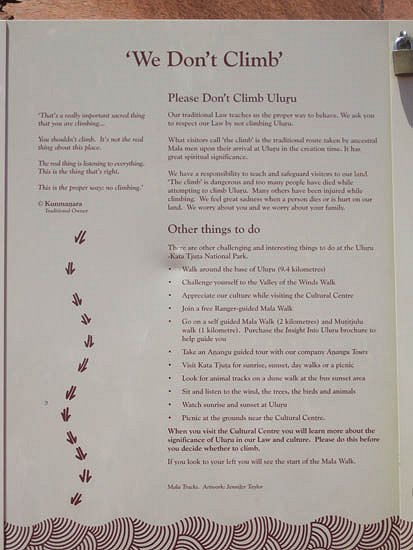

Although there has been some dispute over the actual attitude of the traditional owners of Uluru to continued climbing of the rock, the consensus view is that they oppose the practice.

There appears to be a growing acceptance among international tourists that it is inappropriate and disrespectful to climb Uluru. Attitudes are less clear-cut within Australia, where a number of informal polls have suggested that a majority of potential Australian tourists to the Northern Territory believe that climbing the rock should continue.

Thus, the dispute over climbing Uluru appears to be part of the continuing debate within Australia over how to reconcile the conflicting views of Australia's past and its significance held by Indigenous Australians and many Australians of European origin. It occupies a place alongside debates over a national apology, a treaty, recognition within the Constitution and whether Australia should be regarded as having been 'settled' or 'invaded' by European peoples.

Focusing purely on the issue of whether Uluru should be climbed, a compromise solution would appear to be to better develop alternative tourist experiences in the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. There have been attempts to do this over a number of years.

On May 12, 2016, The Conversation published a comment by Marianne Riphagen, Visiting Fellow at the Australian National University. Between 2013 and 2015, Riphagen conducted 20 weeks of research at Uluru as part of a study undertaken by the Australian National University, in association with Macquarie University, examining how the Anangu use their cultural heritage to earn a living.

The article contends that more needs to be done to make it possible for the Anangu to economically exploit their cultural heritage without having to adopt practices which violate their beliefs.

Riphagen outlines a number of current impediments 'in the attempt to develop sustainable and culturally appropriate alternatives to climbing Uluru. One' she claims, 'is the tight operational budget for Australia's park agencies.

At Uluru, Parks Australia has faced some particularly challenging years, as a decline in tourists - from 349,172 in 2005 to 257,761 in 2012 - caused revenue from the sale of entry tickets to fall.

At the same time, lack of funding has meant that the Uluru Cultural Centre, where tourists are encouraged to begin their visit to the park and learn about Anangu culture, hasn't been maintained properly. It looks dilapidated, and anything but an alternative to climbing.'

Rather than attempt to boost the Red Centre tourist industry by promoting the climbing of Uluru against the wishes of the traditional owners, Riphagen suggests that Adam Giles 'should consider resolving the conflicting agendas, governance challenges and funding difficulties that characterise the Uluru economy.'

Riphagen maintains, 'Once tourists can enjoy various sustainable products based on Anangu culture, the destination will become truly unforgettable and benefit Anangu economically. Then, the Uluru climb can be closed.'