Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Further implications

Further implications

There are inevitable tensions in a democracy.

Elected governments gain legitimacy because they have been endorsed by a majority of the electorate. Rule through consent of the governed is a fundamental principle of democracy.

However, the consent of the governed is largely dependent on the electorate believing that their government is acting in their best interests. This belief seems to have broken down in many Western democracies.

Repeatedly in Australian political focus groups, designed to gauge voter attitudes, the complaint is made that politicians, and party leaders in particular, are 'out of touch'. Politicians are condemned for having no interest in or understanding of the lives of the average voter. Part of this appears to be based on the belief that politicians are overpaid and privileged. 'Never had to live on the sort of money we've got to get by on'; 'they don't know how we live'.

Allegiances to particular parties are breaking down. Voters no longer exhibit automatic loyalty to a particular party. This point was underlined by former Prime Minister John Howard in a speech given to the Australian Institute of International Affairs in October, 2017. Howard identified a 'fragmentation' of support and a reduction in the automatic attachment voters once had to the major parties.

It has been estimated that between 30 and 40% of the Australian electorate may now be composed of 'swinging voters', electors whose vote may readily change from one election to another.

It has been estimated that between 30 and 40% of the Australian electorate may now be composed of 'swinging voters', electors whose vote may readily change from one election to another.  More significant is the probability that these voters do not automatically assume that either of the major parties are currently serving their interests.

More significant is the probability that these voters do not automatically assume that either of the major parties are currently serving their interests. Associated with a lack of support for the traditional parties has been a growing interest in independent candidates or candidates from small parties representing narrow sectional interests. A parliamentary research paper released in September 2010 concluded, ' Against the decline in support for major parties, there has been a slow but steady increase in support for independent candidates in federal and state elections since 1980.'

It seems that a significant section of the electorate is looking for representatives who better serve their interests.

It seems that a significant section of the electorate is looking for representatives who better serve their interests.These developments have significant implications for the operation of Australian democracy. Declining support for the major parties in recent times is leading to more non-majoritarian outcomes at elections. Particularly in the Senate, where Government majorities have been historically uncommon, governments have had to form alliances with a variety of independents or small party representatives in order to get their program accomplished. This has a number of consequences. It may make governments more responsive to minority views; it may also make governments less able to implement their programs which feeds community perceptions that they are weak, incompetent and ineffectual.

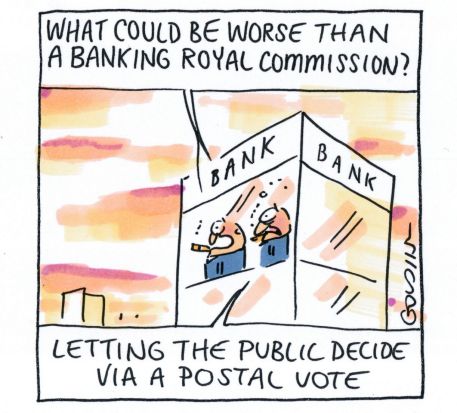

Calls for an increased use of plebiscites or perhaps of the newly developed postal survey are interesting in this context. In November, 2016, independent Jacqui Lambie stated her intention to work with small party leader Pauline Hanson, to have a number of plebiscites conducted at the same time as the next federal election. Senator Lambie wanted a ballot held on same-sex marriage, indigenous recognition, and euthanasia.

On the one hand, gauging the popular view on current issues may make political parties more sensitive to the wishes of the electorate. Acting more clearly in accord with the popular will may also give government policies more legitimacy than they currently enjoy among many voters.

On the other hand, there are concerns as to whether majoritarianism inevitably produces the best policy outcomes. One of the reasons representative government was established was the belief that governing required expert knowledge and deliberative judgement. The electorate cannot be assumed to have either.

Parliamentarians have access to Parliamentary libraries, the work of Parliamentary researchers and to the submissions of those responding to a particular bill. They participate in committees that investigate issues of concern. They have the opportunity to develop expertise and the time to deliberate. Governments have the whole apparatus of the Public Service to support their policy formulation.

If Australia ultimately develops a mode of government that makes greater use of instruments of direct democracy such as referenda and plebiscites then there is a need to ensure that all members of the electorate are as informed as possible before they form a decision and cast a vote.

The way in which the South Australian Government responded to a Royal Commission recommendation that a nuclear fuel cycle facility be established in the state is illustrative. Following the release of the Royal Commission Report recommending the setting up of the waste facility, the Premier announced the establishment of the Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission Consultation and Response Agency (CARA) to increase awareness of the Royal Commission's report and facilitate a community consultation process.

There were four elements in this community consultation and decision-making process - two citizens' juries and a series of more than 100 informal consultative meetings around the state at which citizens were invited to receive information and give feedback before a final referendum was to be held. Ultimately the referendum did not proceed because the proposal to establish the facility was rejected by two-thirds of the second citizens' jury.

The above process demonstrates the degree of citizen education and pre-consultation that may need to be undertaken before a plebiscite or referendum on a significant and complex issue was held.