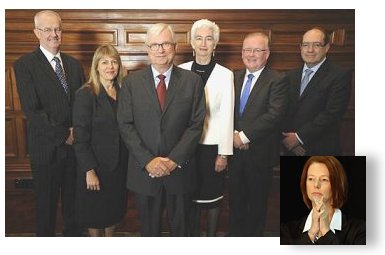

Right: The Royal Commissioners and (inset) former Prime Minister Julia Gillard, who set up the commission to inquire into claims of abuse in churches and other organisations and institutions

Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Arguments in favour of the mandatory reporting of admissions made in the Confessional

Arguments in favour of the mandatory reporting of admissions made in the Confessional

1. Churches are not outside the operation of the laws of the State

Australia has no established Church. This means that under the Australian Constitution there is no provision for the State to give a favoured position to a particular religion. No religion in Australia is the official religion of the country and all religions within the country are meant to be treated equally.

Section 116 of the Australian Constitution provides that: 'The Commonwealth shall not make any law for establishing any religion, or for imposing any religious observance, or for prohibiting the free exercise of any religion, and no religious test shall be required as a qualification for any office or public trust under the Commonwealth.'

However, this does not mean, as some commentators have suggested, that there is a legal separation between Church and State and that Australian governments cannot make laws that affect religious institutions. The state does interact with religion. For example, the federal government funds schools run by religious organisations and recognises marriages conducted by religious celebrants.

However, though Australian law theoretically governs the churches in this country, religious organisations have been given a number of exemptions from the operation of some Australian laws. For example, in the area of legal protection against discrimination, in most Australian states, religious schools have the capacity to discriminate in their employment practices on the basis of whether a potential employee accords with the religious ethos of the school. This is counter to the anti-discrimination laws that are in place across the country.

However, church agencies and schools are not exempt from anti-discrimination law in New South Wales and Tasmania.

Where it operates, this capacity to discriminate has been specifically written into a particular law; it is not an intrinsic feature of Australia's constitutionally determined relationship to the different churches. The default position is that Australian law applies to all groups irrespective of religious affiliation.

Where it operates, this capacity to discriminate has been specifically written into a particular law; it is not an intrinsic feature of Australia's constitutionally determined relationship to the different churches. The default position is that Australian law applies to all groups irrespective of religious affiliation.

There is increasing pressure to remove legal exemptions historically granted churches in Australia. For example, it was announced in February, 2018, that survivors of sexual abuse will soon be able to sue churches in Victoria, as the State Government moves to close a legal loophole. Currently, laws in the state prevent victims from being able to take legal action against some non-incorporated organisations, like churches.

Attorney-General Martin Pakula said the new legislation, which was passed in May, was in response to a key recommendation from the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse.

Under previous laws, a church could not be sued because it does not legally exist as its assets are held in a trust. This is known as the 'Ellis defence'. Courts will now have the power to appoint trustees to be sued if those institutions fail to nominate an entity with assets and allow the assets of the trust to be used to satisfy the claim. Similar laws are in train in New South Wales.

2. Religious freedom is not absolute

Those who argue that the Seal of the Confession should be restricted claim that the right to practise religion is an important freedom but not one that overrides all others.

Peter Johnstone, a committed Catholic and a member of Catholics for Renewal, who gave public evidence to the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse has stated, 'It is fundamentally important to uphold the right of a person to freely practise their religion in accordance with their beliefs. But that right is not absolute. No society can afford simply to allow religions to demand exemption from laws made for the good of society...'

Peter Johnstone has further noted, 'The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights provides that religious freedom may be the subject of...limitations to protect public safety, order, health, or morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others.'

The same point has been made by Sarah Joseph, director of the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law at Monash University, who has stated, '(Religious freedom) is not an absolute right so, for example, it can be limited by laws which are necessary to protect ''the fundamental rights and freedoms of others''. Clearly, many manifestations of religious belief, such as polygamy or female genital mutilation, may be prohibited due to their impacts on the rights of others.'

The Australian federal Parliament's 'Definition and Scope of the Right to Freedom of Religion or Belief' explains the circumstances under which limitations may reasonably be imposed on the individual's freedom to practise religion. Among the grounds it states as sufficient to restrict religious freedom is the need to protect public safety. Public safety is defined as 'protection against danger to the safety of persons, to their life or physical integrity'.

Advocates against child abuse argue that this crime is a clear violation of children's right to 'safety' and 'physical integrity'. Any religious practice which could be seen to increase the likelihood or allow the continuation of child abuse should be banned or restricted.

Advocates against child abuse argue that this crime is a clear violation of children's right to 'safety' and 'physical integrity'. Any religious practice which could be seen to increase the likelihood or allow the continuation of child abuse should be banned or restricted.The position of the federal Parliament has been summed up as 'As a practical matter, it is impossible for the legal order to guarantee religious liberty absolutely and without qualification ... Governments have a perfectly legitimate claim to restrict the exercise of religion, both to ensure that the exercise of one religion will not interfere unduly with the exercise of other religions, and to ensure that practice of religion does not inhibit unduly the exercise of other civil liberties.'

3. Abuse has been allowed to continue because of the Seal of Confession

Evidence presented before the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse and admissions made by other child abusers have demonstrated that the Seal of the Confession has allowed abuse to continue.

Chrissie Foster, whose two daughters were both sexually abused by a Catholic priest, has drawn attention to abuse that was not stopped because of the Seal of the Confession. Foster has noted, 'In Queensland in October 2003, Catholic priest Michael McArdle pleaded guilty to sexually assaulting generations of children. In a sworn affidavit which he made public, McArdle stated he had confessed to sexually assaulting children 1500 times to 30 different priests over a 25-year period in face-to-face confessions.'

Foster argues, 'It reveals a noxious secret between priests and a paedophile priest which facilitates and enables heinous crimes to continue for decades at the expense of children, their lives and their wellbeing.'

Similar cases of priests continuing to abuse children because perpetrators were shielded by the Seal of the Confession have occurred in other countries. In the case of English priest, Father James Robinson, three complaints about Robinson were made by a boy to three separate priests in confessionals between 1972 and 1973. These complaints were not acted on. It was not until 2010 that Robinson was finally jailed for 21 years after decades of abuse.

Gerald Francis Ridsdale, a laicised Australian Catholic priest, was convicted between 1993 and 2017 of sexual abuse and indecent assault against 65 children some aged as young as four years. Ridsdale agreed with the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse that 'from my experience and what I've done and the damage that I've done' the confessor should tell the police if someone had confessed to a crime.

Peter Johnstone, a committed Catholic and a member of Catholics for Renewal, who gave public evidence to the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, has paraphrased the Commission's position: 'The Commission heard evidence of a number of instances where disclosures of child sexual abuse were made in Confession, by both victims and perpetrators. The Commission found that Confession is a forum where Catholic children have disclosed their sexual abuse, and where clergy have disclosed their abusive behaviour.... The Commission heard evidence that perpetrators who confessed to sexually abusing children went on to reoffend...'

Johnstone has urged, 'The evils of clerical child sexual abuse exposed by the Royal Commission require fundamental reforms of Church governance and culture, including canon law provisions, especially the seal of confession.

The Royal Commission's recommendation is necessary in the interests of the safety of our children; it is clearly proper that any person with knowledge of a predator at large should bring that person to the attention of the police.'

4. Confession may psychologically encourage some abusers in their pattern of abuse

Critics of the role of Confession have argued that in some cases it may actually have psychologically encouraged child abusers in their behaviour.

The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse said in their summary statement, 'We are satisfied that confession is a forum...where clergy have disclosed their abusive behaviour in order to deal with their own guilt. We heard evidence that perpetrators who confessed to sexually abusing children went on to reoffend and seek forgiveness again.'

Chrissie Foster, the mother of two daughters sexually abused by a priest, has suggested that the relief from guilt offered by absolution may actually act as an opportunity for child abusers to continue to offend. Foster has highlighted the case of former Queensland Catholic priest, Michael Joseph McArdle, who was jailed for six years for child abuse perpetrated over a period of 25 years.

In his affidavit McArdle stated about his crimes: 'I was devastated after the assaults, every one of them. So distressed would I become that I would attend confessions weekly.' After each confession he said, 'It was like a magic wand had been waved over me.'

In an opinion piece written the year before, Foster commented on the effect of this absolution. She stated, 'The confessional forgiveness gave him a clean slate that allowed him, within the week, to reoffend - a cycle that lasted for several decades.'

Foster concluded, 'If McArdle had not been forgiven perhaps his guilt would have compelled him to get help or surrender himself to police... Confession totally aided and abetted McArdle in prolonging his unspeakable sexual crimes against the most defenceless - children.'

The same point has been made by Sarah Joseph, director of the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law at Monash University, who has stated, 'The availability of religious absolution for such despicable crimes has exacerbated the institutionalisation of the problem by providing an easy way out for the perpetrator's conscience.'

A study published in Psychology Today in November 2013 suggested that rituals of cleansing and absolution do not necessarily provoke improved behaviour. The author stated, 'Awareness of moral transgression prompted individuals to seek physical cleansing; but once (symbolically) cleansed, individuals were actually less motivated to behave altruistically. This suggests that rituals of absolution may make people feel better, but they don't make people behave better.'

5. The Anglican Church has limited the Seal of the Confessional

Those who argue that the Catholic Church should remove the Seal of Confession from child abusers note that the Anglican Church has already done so.

Historically, the Anglican Church has pledged not to reveal to civil authorities crimes admitted in Confession. The 1989 Anglican Canon Concerning Confession states, 'If any person confess his or her secret and hidden sins to an ordained minister for the unburdening of conscience and to receive spiritual consolation and ease of mind, such minister shall not at any time reveal or make known any crime or offence or sin so confessed...without the consent of that person.'

Despite this 1989 ruling and a similar prior Cannon of 1603, the Anglican Church does not treat the confidentiality of Confession as absolute. For example, a 17th century minister who heard a confession of treason was not required to keep that confession confidential.

In March, 2016, the Doctrine Commission of the Anglican Church of Australia noted, 'This single exception (in regard to treason) is very important, because it establishes both that confidentiality is of the utmost importance, and also that exceptions could be made under extraordinary circumstances.'

Anglican acceptance that exceptions can be made to the confidentiality of Confession has allowed the Anglican Church of Australia to modify its doctrinal position. The Anglican Church now allows its ministers the freedom to report to the police child abusers who admit their crime in confession.

On July 3, 2014, it was reported that the Anglican Church had shifted its position on the confidentiality of Confession. The general synod had voted for a change to cover serious crimes, such as child abuse. The synod decided it would be up to individual dioceses to adopt the policy.

The Anglican Archbishop of Adelaide, Jeffrey Driver, stated, 'In matters where lives and genuine wellbeing of people is at risk, the Church has decided that a priest may disclose [but] it's not saying a priest must disclose...'

Critics have wondered where the Catholic Church might be willing to take a lead from the Anglican Church. Theological writer, Alison Coates, has asked, '(Will) the Roman Catholic Church...also see that what was good theology in 1215 may not be so useful, or even moral, 800 years later?'