Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Further implications

Further implications

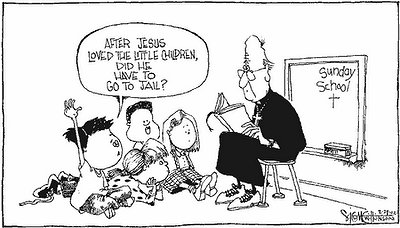

Already half of Australia's states and territories have accepted the recommendation of the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse to require priests to report child sexual abuse admitted during Confession.

This will pose no significant problem for the Anglican Church in Australia. In 2014, Australia's Anglican Church altered its position on the confidentiality of Confession. The general synod voted for a change to cover serious crimes, such as child abuse, admitted to during Confession. The change gave ministers the freedom to report what they had been told to civil authorities. The synod decided it would be up to individual dioceses to decide whether or not they adopted the new policy. Ultimately, responsibility for what action he or she takes will rest with each Anglican minister in Australia.

Shortly later the Church of England debated whether it would follow the lead of the Anglican Church of Australia and similarly allow ministers to report what they had heard in Confession. As of July, 2018, no agreement had been reached.

What this demonstrates is the decentralised nature of Anglicanism. There is no overall controlling body. There are nearly 40 independent Anglican national churches, none of which has authority over any other. There is no Parliament or Congress. There is certainly a Church of England. But there is also the Church of Wales, the Church of Ireland, and the Scottish Episcopal Church, none of which is governed by the Church of England. The Anglican church was originally spread to other countries through English colonization. As the colonies became independent from England, so did their churches. There is a structure for doctrinal centralization, but in the absence of central authority the doctrine is followed by consensus and not by mandate.

There is significant theological and doctrinal divergence within the Anglican Communion. Since World War II, for example, most but not all provinces have approved the ordination of women. More recently, some jurisdictions have permitted the ordination of people in same-sex relationships and authorise rites for the blessing of same-sex unions.

This diversity means that Anglican churches in particular nations can make rulings that reflect the attitudes of their particular national church. They also allow for individual dioceses to decide on their implementation of national rulings. This doctrinal diversity and flexibility helps to explain the decision taken by the Anglican Church of Australia to relax prohibitions on breaking the seal of the confession.

The far more centralised nature of the Catholic Church makes it much more difficult for doctrinal changes to occur. Most doctrine within the Catholic Church is derived from scripture and endorsed by hundreds of years of tradition. These statements of belief are not amenable to change. Enormous doctrinal authority rests with the Pope; however, he would not make doctrinal rulings that could not be reconciled with scripture and established tradition. The centralised authority of the Pope typically serves to reinforce tradition rather than to challenge it.

There appears no doctrinal room within the Catholic Church to dispute the seal of the confession. The Catholic Catechism in its statements regarding the Sacrament of Penance and Reconciliation says of the secrecy of the sacrament, it 'admits of no exceptions'.

The laws that are being framed in various Australian states and territories requiring priests to notify authorities of child sexual abuse revealed in Confession would have to be sanctioned by the Holy See (the central government of the Catholic Church) if they were to be followed by Catholic priests in Australia. It seems certain that this will not occur. The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse seems to have already recognised this.

In its recommendations, the Commission called on states and territories to extend mandatory reporting provisions to include what priests are told during Confession. However, it did not ask Australian bishops to approach the Holy See to request that Canon law be altered to allow some exceptions within the operation of the seal of the confession.

Without doctrinal allowance, these new Australian state and territory laws are unlikely to have very much effect. No priest is likely spontaneously to volunteer information to police or other civil authorities. If questioned, priests will almost certainly refuse to answer. It is hard to see what in real terms these new laws will achieve.

Some critics have argued that unless the Catholic Church in Australia accepts legal liability for the criminal activities of priests and others within its ranks engaged in or supporting sexual abuse, the exemptions and concessions allowed the Church, such as exemptions from taxation, should be revoked.

The federal government would have to impose such a penalty and is unlikely to do so; however, even its suggestion is an indication of how grim the contest between these two conflicting areas of authority, civil and religious, could become.

The federal government would have to impose such a penalty and is unlikely to do so; however, even its suggestion is an indication of how grim the contest between these two conflicting areas of authority, civil and religious, could become.