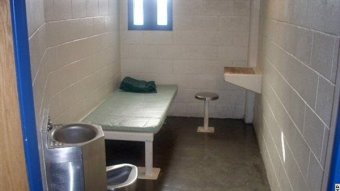

Right: A typical cell at Victoria's newest prison, Ravenhall.

Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Arguments opposing Victoria's prison policies

Arguments opposing Victoria's prison policies

1. Victoria's prison population has increased dramatically and is resulting in increased violence and management issues

After a historic low rate of 38 prisoners per 100,000 people in 1977, the imprisonment rate has shown a continual upward trend. In 2017, it reached 113.1 prisoners per 100,000 people, a rate not seen in Victoria since 1896.

The number of people in Victoria's prisons has doubled over the past decade to more than 8,100. Recent projections suggest the growth will continue into the foreseeable future, with prisoner numbers expected to soar to 11,130 within four years.

Women are being imprisoned in Victoria in record numbers. The female prison population has grown 140 per cent over the last ten years. Official projections show that growth in the incarceration of women is set to continue by another 40 per cent from now until mid-2023.

Critics concerned by current trends have noted 'the explosion in the number of low-level female offenders on remand, ineligible for bail, unable to get a timely hearing or incapable of meeting conditions for their release such as stable housing.' The government forecasts the number of female remandees to rise by almost 60 per cent, overtaking the number of female sentenced prisoners by 2023.

The number of Indigenous women incarcerated has grown at an even greater rate. The figure is up 240 per cent over the past five years, with Indigenous women now making up 13 per cent of female prisoners despite being only 0.4 percent of Victoria's population.

At the current rate of growth, Corrections Victoria will exceed its planned capacity for housing female prisoners before reaching the end of the government's four-year forecast period in 2023, leaving a shortfall in beds.

It has further been noted that many of those in prison, whether male or female, are either awaiting trial or sentencing. The number of prisoners in remand in Victoria has almost doubled since the Andrews government came to power. More than a third of people behind bars in Victoria are on remand.

Sentencing Advisory Council chairman, Arie Freiberg, has stated, '35 per cent of those inside are not convicted.'

Population pressure in Victoria's prisons is having an adverse effect on prison management and is precipitating riots. Overcrowding contributed to the largest prison riot in Victoria's history when inmates caused $10 million worth of damage at the maximum-security Metropolitan Remand Centre in 2015. In March 2016, it was revealed that Corrections Victoria was so overwhelmed by inmate numbers it was failing to bring prisoners on remand to court appearances.

A Department of Justice report released in November 2014 found overcrowding in Victorian prisons is linked to an increase in violence and escapes. The report stated, 'The increase in capacity has also understandably coincided with an increase in the number of incidents at the prison.'

Department of Justice data has also revealed that Victoria has the most violent prisons in Australia, with a prison officer assaulted every three days. The Commonwealth Public Sector Union, which represents prison officers, has claimed the rise in violence is linked to prison overcrowding.

2. Increasing imprisonment is unnecessary as the crime rate in Victoria is declining

Critics of Victoria's growing prison population argue the increased rate of incarceration is not justified as crime rates are declining.

Figures released from the Crime Statistics Agency Victoria in September 2018 show the state's criminal incident rate fell to 5,922 cases per 100,000 people in the last financial year - down from 6,420 a year earlier, and 6,432 the previous year. The offence rate also fell, dropping 7.0 per cent to 7,835. Victoria Police deputy commissioner Shane Patton said the number of victims had dropped by 24,000 over the year to the end of June.

The total number of criminal incidents across the state fell 1.6 per cent to 384,183 in the 12 months to September, the lowest numbers since 2015.

Property damage is down 4 per cent, burglaries are down 16.3 per cent and justice procedure offences are down 7.3 per cent. Theft is also down 8.5 per cent while drug-dealing and trafficking is down 5.2 per cent.

Critics who question the need for increasing the number of people in prison when overall crime rates are falling argue that incarceration is not the cause of a reduction in crime. Instead, critics claim, incarceration rates across Australia are bounding ahead of crime figures and seem to reflect electorates' and politicians' perceptions as to what needs to be done rather than the reality.

New South Wales' chief crime statistician, Dr Don Weatherburn, the director of his state's Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, told the National Applied Research in Crime and Justice Conference in Brisbane in 2016 that research had shown a 10 per cent increase in imprisonment only delivers a 1-2 per cent fall in crime, which does not account for the 40 to 70 per cent falls, depending on the offence, recorded in Australian states and territories over the past 15 years. Dr Weatherburn stated, 'You'd think this dramatic fall in crime would bring with it a dramatic fall in imprisonment rates and a dramatic turnaround in public attitudes towards offenders, but you'd be wrong.'

Dr Weatherburn argues that increasing imprisonment has become a conditioned political reflex rather than a considered response to the actual incidence of crime. He has stated, 'Having pushed the law and order merry-go-round as hard as they could for more than 15 years, politicians found to their surprise that it was hard to get off. So, the tougher laws kept coming.'

In a 9 News report televised on December 11, 2018, Dr Weatherburn noted that Australia's declining crime rate is not recognised by the general population. Dr Weatherburn cited Australian Bureau of Statistics figures which indicate that the murder rate in the year 2000 was 1.6 per 100,000 people. By 2017, it had halved to 0.8 per 100,0000. Over the same period, robbery dropped by 58.8 percent and break and enter dropped by 59.7 percent. Since 2008, there has also been a drop in the rate of assaults. Dr Weatherburn stated, 'The trouble is, of course, public opinion hasn't kept pace with that [decline in crime]. It takes a long time for public opinion to catch up with the facts, partly because shock jocks keep banging on about crime even when it's falling.'

Research has shown that relative to jurisdictions overseas, the Australian public overestimates the level of violent crime and underestimates the current severity of sentences with over 80 percent of respondents believing harsher sentences should be given to offenders.

3. Imprisonment does not reform inmates and causes additional social damage

Critics of Victoria's growing reliance on incarceration to manage crime argue that prisons are not achieving prisoner rehabilitation and may be increasing offenders' likelihood of reoffending.

Research undertaken by the Victorian Justice Department in 2017 indicated that nearly half of all prisoners who have completed their sentence will return to jail within two years. The annual report from the Department of Justice showed 43.6 per cent of adult prisoners were incarcerated within two years of leaving jail. The figure was up from 42.8 percent in 2016.

Prisons have been placed under pressure because of more inmates on remand and changes to parole laws, which have increased prisoner numbers. The overcrowding has negatively affected services designed to rehabilitate prisoners, including education and employment. The Justice Department report showed that just 34 per cent of prisoners were involved in education.

Concern has also been expressed regarding the growing numbers of young prisoners within Victoria's prisons, especially young prisoners from particular ethnic groups. The report highlighted a developing demographic of teen prisoners, with 40 per cent of young people detained or on parole coming from Aboriginal, Pacific Islander and east African, mainly Sudanese, communities. Youth Parole Board chairman, Michael Bourke, has warned there is a glaring over-representation of these ethnic groups. Judge Bourke said offenders with present or past child protection involvement also accounted for almost 40 per cent of the population.

Critics are concerned that these young inmates will have their life options permanently diminished and will become a criminal sub-class with no desire or opportunity to improve their condition.

Judge Bourke stated, 'I see, as to those sentenced to youth detention, a growing disproportion of disadvantaged and excluded young people. In my view, there is risk of an entrenched underclass within our young which feels no connection or aspiration to being part of a functional and hopeful community.'

Victorian Victims of Crime Commissioner, Greg Davies, argues that the community is not gaining very much from the large financial investment the state makes in building and maintaining prisons. Mr Davies has stated, 'I don't think anyone could claim we are getting great value for it. Our recidivism rates in Victoria are at almost 45 per cent. If you were running a business where you did a particular thing in a specific way, and it failed nearly 45 per cent of the time, you probably wouldn't keep your position as the CEO for very long.'

Researcher Andrew Bushnell from the Institute of Public Affairs (IPA) has similarly stated, 'We are not really getting bang for our buck... This is a massive intervention into people's lives. If we are going to be undertaking it, how do we do it most effectively?... If we are putting people into prison who can safely be punished outside of prison, then obviously we are taking on a much greater cost than we need to.'

Victorian Ombudsman Deborah Glass is similarly concerned about a lack of effectiveness. Glass has stated, 'One in every two prisoners are leaving prison, then committing crime and going back there. The question we need to ask is: what are we doing to make sure people get out of prison and don't go back?'

Concern has also been expressed about the damage inflicted upon the families of prisoners, especially their children. Some 67,500 Victorian children have a parent appear as defendants in the criminal court each year, while 38,000 children in Victoria annually have a parent in prison. These estimates are somewhat dated and likely to be underestimates, given the Victorian Government's commitment to increasing prisoner numbers. Typically, around 50 percent of prisoners are thought to be parents. Parental imprisonment for many children is both stigmatising and shameful, and actively concealed by many of their families.

Among the traumatic experiences undergone by the children of prisoners are the arrest processes; the consequences of both their parents' behaviour and the decisions of the adult criminal court, which has no clear protocols for considering hardship to children in sentencing; sudden and forced separation from their parent/s at remand or imprisonment; and the struggle to maintain contact with their parents during the period of incarceration.

4. The financial cost of Victoria's prison system is drawing resources from other government programs

Critics have condemned the Victorian government for its vastly increased expenditure on the state's prisons compared to a far smaller funding increase directed toward services such as hospitals, schools, social housing and mental health services.

In April 2018, it was announced that annual spending on Victoria's prisons had risen by more than $300 million since 2013-2014.

The annual cost of running the Victoria's prisons is now more than $1.6 billion. This is triple the outlay in 2009-2010. In March 2018 a report by the Auditor-General found that the annual cost to the state of managing male prisoners had risen 90 per cent, from $425.9 million in 2010-11 to $811.2 million in 2016-17. Each prisoner costs the state $127,000 a year on average, the report found.

In addition to the increasing expenditure involved in maintaining prisoners in jail, in the May 2019 budget, the government announced a record $1.8 billion in new capital spending on prison infrastructure over four years to accommodate 1600 additional prisoners.

An analysis conducted by RMIT emeritus professor David Hayward shows that the increase in spending on corrections is outstripping that for most other areas of government, including on hospitals, schools and social housing.

The huge increase in spending on the state's prisons has been compared unfavourably with the far smaller $200 million the Victorian government has pledged to spend on social housing over the next three years. Melanie Poole, a consultant at the Federation of Community Legal Centres, has noted that a lack of secure housing was a key factor in imprisonment, and that an investment in social housing could cut crime and imprisonment rates. Ms Poole stated, 'We know that one in four women who go to prison are affected by homelessness.'

In June 2019, The Guardian reported Victoria spends about half the national average per person on social housing and has about 80,000 people on the public housing waiting list, including 25,000 children. It also reported on criticism the government has received for channeling far greater funds into building prisons. The Victorian Council of Social Service chief executive, Emma King, has claimed, 'The budget blows almost $2bn on...mega prison[s]. For $2bn, we could have built tens of thousands of social housing units to fight homelessness.'

Critics of the Victorian government's expenditure on prisons also condemn its reduced funding of mental health services. It has been estimated only one in three Victorians in need of mental health care are able to access it. This access figure is nearly 40 per cent lower than the national average, according to Australian Institute of Health and Welfare data, and means more than 120,000 Victorians with mental health issues are unable to obtain care.

Patrick McGorry, Professor of Youth Mental Health at the University of Melbourne, has argued Victorian mental health services need a state government investment of $1 billion a year. He unfavourably compared the $700 million being spent to build a single new maximum-security near Geelong to the state's $700 million mental health package. Professor McGorry argues increased investment in mental health would reduce pressure on the state's penal system as many find their way into prison because they lack adequate care for mental health issues. Professor McGorry stated, 'If we had a proper mental health system, we wouldn't need to be building that new prison.'

Even the Victorian premier, Daniel Andrews, who continues to support his state's 'tough-on-crime' policies, has expressed reservations regarding the current spending trajectory for increased building of prisons and maintaining prisoners. Andrews has stated, 'We don't want to get to a place where we're spending more on prison beds than we are on hospital beds.'

5. Laws governing bail and parole are excessive and too inflexible

Opponents of the changes made to Victoria's laws surrounding the granting of bail and parole argue that they are excessive and insufficiently flexible. According to critics, these changes were made in response to extreme cases and so represent an overreaction. The provisions now in place are not, it is claimed, appropriate for most people who apply for bail or parole. Opponents claim these changes are resulting in the mass incarceration of minor offenders who do not represent a serious threat to the community.

Melanie Poole, a consultant and former policy engagement director at the Federation of Community Legal Centres, has stated, 'The Adrian Bayleys and James Gargasoulases of the world are a tiny fraction of the prison population. We do not need a mass incarceration system to deal with these extreme cases.'

It has been claimed that most of those caught in the current crime crackdown are not hardened criminals or sexual and violent attackers. Rather, it has been suggested, Victoria's prisons are becoming increasingly populated by lower-level offenders on remand, ineligible for bail, unable to get a timely hearing or incapable of meeting conditions for their release such as stable housing.

Jill Prior, a criminal lawyer and the principal legal officer for the Law and Advocacy Centre for Women, has stated, 'Those violent and unpredictable offences are outliers, but the laws made in response to them are catching everyone.'

The primary factor in the dramatic increase in Victoria's prison population is the number of offenders being remanded into custody because they are denied bail as a result of tightening bail laws and the response of judges in the wake of high-profile crimes such as the Bourke Street massacre by James Gargasoulas in 2017 and the failed Bourke Street terror attack in 2018.

People on remand now account for 38 per cent of all prisoners in the system, up from 19 per cent five years ago. The projection for 2023 anticipates a four-fold increase in the number of remandees compared to 2014, when the Andrews-led Labor was first elected.

Remandees remain innocent until found otherwise so must be housed away from sentenced prisoners. That means special, well-located facilities that allow ready access to lawyers' services and families. Such provision is costly, and the government is playing catch-up in attempting to provide it. It has also been noted that the surge in offenders on remand is having serious flow-on consequences for the courts, including slow-downs in processing cases when offenders are delivered late, or do not arrive at all, for hearings.

Opponents of the growing number of Victorians in remand argue that remand practices in place for children are particularly unsuitable. These remand provisions pre-date the most recent reforms to the bail system in Victoria taken in response to the Coghlan Bail Review.

In 2014 and 2015 the number of children (those under 18) held on remand in Victoria increased dramatically, including a significant increase in children under 15. This was the result of reforms to the Bail Act in December 2013 that imposed the same conditions and restrictions on children as are applied to adults.

A paper produced by the Jesuit Social Services in 2015 has claimed, 'Failing to distinguish between children and adults in this way puts Victorian practice out of step with the core principles of the Children Youth and Families Act 2005 to act in the best interests of children and to use prison only as a last resort, and is also inconsistent with our international commitments under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.'

It has been noted that children who are highly vulnerable are overrepresented among those on remand and in sentenced detention. The 2015 Youth Parole Board Annual Report showed: 62 per cent were victims of abuse, trauma or neglect; 33 per cent presented with mental health issues; 23 per cent had a history of self-harm or suicidal ideation and 22 per cent presented with issues concerning their intellectual functioning.