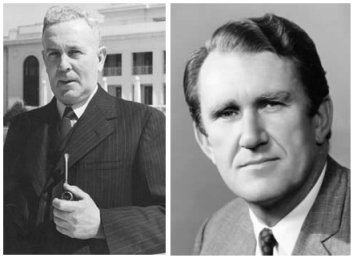

Right: Two former Prime Ministers, Ben Chifley (left) and Malcolm Fraser, were in favour of population growth for, among other reasons, the military security of the nation .

Right: Two former Prime Ministers, Ben Chifley (left) and Malcolm Fraser, were in favour of population growth for, among other reasons, the military security of the nation .

Arguments in favour of a 'big Australia'

1. A 'big Australia' would be a boost for the Australian economy

It has been claimed that strong population growth would protect Australia from the downward economic spiral that results from population decline.

A spokesman for The Victorian Employers' Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Chris James, has claimed, 'What happens when you don't have strong population growth is a situation like Japan where stagnation is the order of the day...When areas depopulate, the level of demand in the economy drops. That effects business, business stops investing, employment falls and people begin to leave, so it effectively feeds on itself.'

A recent report praised Australia's overall population growth of 1.9% in 2008, and credited it as being the reason why Australia fared so much better than other developed countries during the global financial crisis. It stated that in simple economic terms, more people means more customers, which results in more jobs.

In February 2010, the Ethnic Communities' Council of Victoria stated, 'Many of the economic and social concerns raised [about migration and population growth] fail to recognize the profoundly positive social, economic and cultural impact immigrants have made to Australia. Economic concerns generally relate to the increased cost to social welfare and the strain to certain industries such as education and health. Yet immigrants have contributed enormously to Australia's economic prosperity and growth and without immigration the labour force participation rate, a key indicator of economic growth and welfare, would stagnate.'

2. A 'big Australia' would reduce the problem of our ageing population

Australia's population is aging, that is, the proportion of citizens over the age of 60 is growing. This is a consequence of relatively low birthrates and the fact that the 'baby boomer' generation, those born during the period of population growth after World War II, are now in their fifties and sixties. It has been claimed that without an increase in population from both natural population growth and through migration, Australia will not be able to support its aging citizens once they are no longer able to work.

Graham Bradley, the president of the Business Council of Australia, has stated, 'If you look at the intergenerational report, the important conclusion from that is not whether our population is going to be 30 million or 32 million or 35 million or 36 million in 2040. It's about the demographics that are changing in Australia, with the number of retirees that need to be supported by the working population.

And that can't be addressed completely by natural birth rate, which is, of course, increasing as well. So that's why we say we need, over the long term, sustained ... migration, particularly focused around skilled migration.'

Commonwealth Treasury secretary, Ken Henry, has noted that Australia's population is ageing rapidly. He has stated, 'Forty years ago, 8 per cent of us were aged 65 or more. Today the figure is 13 per cent, and 40 years from now it is expected to be 22 per cent. Over the same period, the share of the population in paid employment - and therefore paying taxes to fund the services and pensions of the more numerous elderly - will fall.'

There are those who argue that only substantial population growth, whether through an increased birthrate or through migration will allow Australia to support its growing number of elderly citizens.

3. A 'big Australia' would expand the tax base, allow for economies of scale and improve community services for all Australians

It has been claimed that a larger population would actually fund the services it requires by expanding the tax base governments can draw on.

Aaron Gadiel, the chief executive of Urban Taskforce Australia has claimed that a large population increases the tax base to fund improvements to infrastructure and welfare services. Mr Gadiel has stated, 'We shouldn't be trying to fight it, what we should be trying to do is ensuring that we've got the investment and infrastructure that makes that process easier to manage.

I think people should be focussing on how much state, federal and local governments have been investing in urban infrastructure to help absorb population growth.'

It has also been claimed that a larger population base would be an added incentive to improve many public services. Transport companies would be more inclined to expand services, for example, if they were assured of substantial public patronage. The same is true of the incentive for government investment in infrastructure that population growth supplies. It has also been claimed that increased population allows for significant efficiencies which mean that these services can be supplied at a lower per capita rate and so at a lower cost to each taxpayer.

'Australia's Population Future', is a position paper prepared for the Business Council of Australia by Professor Glenn Withers in April 2004. The paper states, 'For goods and services not traded internationally, population size spreads the costs of public goods and networks such as public administration, transport and utilities and allows for more domestic competition so reducing the domestic prices of these services.'

4. A 'big Australia' would increase Australia's national security

It has been claimed that a larger population would enable Australia to better defend itself in time of war and would make Australia a less attractive target for foreign aggressors.

It has also been suggested that a larger population and thus a larger and better equipped defence force would make Australia a more attractive ally to those countries with whom we are currently in mutual support alliances or with whom we might wish to enter into such alliances in the future.

Australia's wartime prime minister, Ben Chifley, supported a larger Australia. He argued that the 7,517,981 Australians who lived here in 1946 were nervous about our vulnerability to attack from Asia and that a wealthy, well-populated, well-armed friend of America had a much better chance of sustaining alliances and contributing to its own defence.

Former Australian prime minister Malcolm Fraser has also argued that a relatively under-populated Australia is actually a target for envy and aggression from other nations. Mr Fraser has stated, 'If we believe we can maintain Australia at 18 to 20 million people without increasing envy, without marginalising ourselves, without challenge, then we are gravely and seriously mistaken.' Malcolm Fraser has recommended an Australia of 45 million to 50 million by 2050.

The executive chairman of IBIS Business Information, Mr Phil Ruthven, has also stated that Australia's security interests will force acceptance of a bigger population because this and our involvement in a regional government 'is the best way to avoid war'.

Mr Ruthven claims there is also a moral imperative. If Australia is 'fair dinkum about a fair world', he has claimed, it should accept a higher population density. In Asia, the average population density is 85 people per square kilometre. Australia's is just two.

5. A 'big Australia' would promote a more balanced Australian society and avoid a range of social problems

It has been claimed that a stagnant population leads to population imbalances, the degeneration of cities and to crime.

A spokesperson for the Victorian Employers' Chamber of Commerce and Industry has stated, 'What happens when you don't have strong population growth is a situation like Japan where stagnation is the order of the day, or Detroit where depopulation causes urban degeneration and crime.

When areas depopulate, the level of demand in the economy drops. That effects business, business stops investing, employment falls and people begin to leave, so it effectively feeds on itself.'

It has been claimed that a falling national population leads to situations where the only people to remain in a depopulated area are those who cannot afford to leave. Housing prices fall, services decline, there is unemployment and under-employment and a growth in drug-taking, assault, robbery and other crimes against property.

The Australian Treasury's recent Intergenerational Report Treasury outlines the detrimental effect of low population growth, which it illustrates by reference to Japan and Italy. In these countries population decline will mean stagnation, old age dependency issues, serious equity challenges and major social problems.