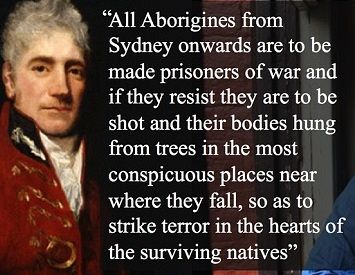

Right: New South Wales colonial-era governor Lachlan Macquarie's 1816 proclamation.

Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Arguments against recognising the treatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as genocide

Arguments against recognising the treatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as genocide

1. The intent of most governors and administrators was not to commit genocide; accusations of genocide made by many historians are false

It has been claimed by some historians and other commentators that the intent of most Australian governors and administrators was not genocidal, that is, they did not aim to exterminate Indigenous peoples. Rather, it has been claimed, their intent was to manage indigenous populations and, if possible, avoid their annihilation. It has further been claimed that the accusations put by some historians that such genocidal practices existed are fabrications.

One example of a supposed misrepresentation of a colonial governor, said to have acted genocidally, is Governor Arthur of Tasmania. In a review published in The Sydney Morning Herald on November 25, 2002, of Keith Windschuttle's 'The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Volume One: Van Diemen's Land, 1803-1847', columnist Paul Sheehan summarised Windschuttle's judgement regarding Tasmania: 'He found the basis for the genocide argument to be speculation, guesswork, outright distortion and blatant ideology...'

Sheehan cites an abbreviated quotation offered by Keith Windschuttle to demonstrate that Governor Arthur's purpose in attempting to gather together all Indigenous Tasmanians was not genocide. The quotation is drawn from Governor Arthur's correspondence with the Secretary of State for the Colonies and states, 'It was evident that nothing but capturing and forcibly detaining these unfortunate savages ... could now arrest a long term of rapine and bloodshed, already commenced, a great decline in the prosperity of the colony, and the extirpation of the Aboriginal race itself.'

Sheehan cites an abbreviated quotation offered by Keith Windschuttle to demonstrate that Governor Arthur's purpose in attempting to gather together all Indigenous Tasmanians was not genocide. The quotation is drawn from Governor Arthur's correspondence with the Secretary of State for the Colonies and states, 'It was evident that nothing but capturing and forcibly detaining these unfortunate savages ... could now arrest a long term of rapine and bloodshed, already commenced, a great decline in the prosperity of the colony, and the extirpation of the Aboriginal race itself.'  (The full text from which Windschuttle derives his quotation can be accessed at

(The full text from which Windschuttle derives his quotation can be accessed at

Defenders of Governor Arthur's actions observe that his intention was not to eradicate all Indigenous Tasmanians but to preserve them initially in an isolated region in Tasmania and later on Flinders Island. These actions were intended to end the hostilities between the Indigenes and the white settlers. Sheehan notes 'Arthur was not expressing concern that the Aborigines presented a threat to the survival of the colony...he was concerned about the survival of the Aborigines themselves.'

On February 11, 2003, Windschuttle addressed The Sydney Institute. He opened his speech by outlining some of the claims of genocide which he disputed. He stated, 'Over the past 30 years, university-based historians of Aboriginal Australia have produced a broad consensus. They have created a picture of widespread killings of blacks on the frontiers of settlement that not only went unpunished but had covert government support. Some of the Australian colonies engaged in what the principal historian of race relations in Tasmania, Lyndall Ryan, has called "a conscious policy of genocide". In Queensland, according to the University of Sydney historian, Dirk Moses: "... the use of government terror transformed local genocidal massacres by settlers into official state-wide policy".'

Windschuttle then gave a detailed account of his work checking the sources upon which such claims were made and concluded that many were based on 'misrepresentation, deceit and outright fabrication'.

Regarding the overall intent of actions often condemned as genocide, Windschuttle revisits his treatment of Governor Arthur and the 1830 'Black Line'. Windschuttle states, 'Despite its infamous reputation, Van Diemen's Land was host to nothing that resembled genocide, which requires murderous intention against a whole race of people. In Van Diemen's Land, the infamous, "Black Line" of 1830 is commonly described today as an act of "ethnic cleansing". However, its purpose was to remove from the settled districts only two of the nine tribes on the island to uninhabited country from where they could no longer assault white households.'

Many see claims such as Windschuttle's that 'genocide...requires murderous intent' as significant. In 2003 The International Association of Genocide Scholars published an article by Katherine Goldsmith in which she noted 'Genocide has been dubbed the ''crime of all crimes'' and, for some, should require the highest form [of evidence] of intent'. There is concern that the crime of genocide not be generalised or trivialised and that only those actions with a specific genocidal intent by regarded as genocide. International lawyer, Guenael Mettraux, has stated, 'genocide was adopted to sanction a very specific sort of criminal action. It would be regrettable to denature genocide for the sake of encompassing within its terms as many categories and degrees of criminal involvement as possible.'

For critics such as Keith Windschuttle that intent to commit genocide was not present.

For critics such as Keith Windschuttle that intent to commit genocide was not present.2. Violent deaths at the hands of white settlers and administrators were a relatively minor cause of Indigenous population decline

Historians and commentators who argue that Indigenous genocide did not take place tend to focus on acts of violence against Indigenous people and argue that only large-scale loss of life brought about in this manner can be regarded as genocide. They dispute the number of violent deaths which occurred and claim that the impact of such deaths on Indigenous populations was in fact quite small.

The chief exponent of the view that relatively few Indigenous lives were lost in violent conflict with either white forces or white settlers is Keith Windschuttle. When considering the total of Indigenous lives lost through violence in Tasmania between 1803 and approximately 1830, Windschuttle argues that the figure was only 120. This is in sharp distinction to historians such as Lyndall Ryan who claimed that the figure was closer to 700.

Windschuttle vigorously disputes Ryan's use of sources while his own has been praised as 'forensic' by those who support his conclusions.

Windschuttle vigorously disputes Ryan's use of sources while his own has been praised as 'forensic' by those who support his conclusions.

Windschuttle argues that the violent taking of Indigenous lives was a relative rarity and that it was not sanctioned by early governors. He has stated, ''The British officials who were posted to Tasmania were enlightened humanitarians...The idea of killing Aborigines would have mortified them.'

Windschuttle further claims that some supposed 'massacres' were either invented or misattributed. He refers to the supposed Mistake Creek Massacre alluded to and apologised for by former Governor General Sir William Deane. Windschuttle states, 'Deane got the facts of this case completely wrong. According to the Western Australian police records, the incident took place in 1915, not the 1930s. It was not a massacre of Aborigines by whites and had nothing to do with a stolen cow. It was a killing of Aborigines by Aborigines in a dispute over a woman who had left one Aboriginal man to live with another. The jilted lover and an accomplice rode into the camp of his rival and shot dead eight people.'

Commenting on Windschuttle's challenge to Sir William Deane's interpretation of the historical event, then Sydney Morning Herald columnist Paul Sheehan stated, 'Deane, for one, might one day reflect on his role in defaming the Australian people on the basis of shabby evidence.'

Windschuttle takes issue with suggestions that such disputes over detail are not significant. He states, '[I]t does matter greatly whether stories about crimes of this magnitude are accurate in their details...If the factual details are not taken seriously, then people can invent any atrocity and believe anything they like. Truth becomes a lost cause.'

Windschuttle and others who hold his views see themselves in direct opposition to historians who claim that a violent genocide took place in colonial Australia. He states that his work is intended to mount 'a frontal assault on the accusation of genocide which began with a claim, now accepted as fact around the world and taught in schools, that the Tasmanian Aborigines were exterminated by a policy of genocide.'

Windschuttle and those who hold similar views do not dispute that the "pure-blood" Indigenous population had all but died out by the 1840s. What Windschuttle contests is the manner of that demise. He attributes it to the effect of disease and Indigenous interbreeding with whites. This last Windschuttle accounts for through the Indigenes' commodifying their women, whom he at another point suggests willingly formed relationships with white mean, rather than doing so as a result of abduction and rape. Windschuttle claims, 'The full-blood Tasmanian Aborigines did die out in the nineteenth century, it is true, but this was almost entirely a consequence of two factors: the 10,000 years of isolation that had left them vulnerable to introduced diseases, especially influenza, pneumonia and tuberculosis; and the fact that they traded and prostituted their women to convict stockmen and sealers to such an extent that they lost the ability to reproduce themselves.'

Accounts such as Windschuttle's regard violent deaths at the hands of white settlers and administrators as a relatively minor cause of Indigenous population decline. They further consider that such deliberate, violent action is necessary for genocide to have occurred. They therefore conclude that there was no genocide.

Accounts such as Windschuttle's regard violent deaths at the hands of white settlers and administrators as a relatively minor cause of Indigenous population decline. They further consider that such deliberate, violent action is necessary for genocide to have occurred. They therefore conclude that there was no genocide.3. Declaring that white Australia has committed genocide would be divisive

Critics of the use of the term genocide to describe the deaths of large numbers of Indigenous people since British colonisation have argued that such a depiction of Australia's history is divisive. It has been claimed that it puts the worst possible construction on the reason for these deaths. As such, it serves to provoke hostility among Indigenous Australians. It also provokes guilt among many non-Indigenous Australians who accept the accusation and anger among those who do not. The general contention is that it serves to set one group of Australians against another.

This view has been put by historian Geoffrey Blainey, who, during his Sir John Latham lecture of 1993, stated, 'The black armband view, while pretending to be anti-racist, is intent on permanently dividing Australians on the basis of race.' The phrase 'black armband view', coined by Blainey, refers to a perspective on Australian history which focuses on the negative and encourages a sense of national guilt or remorse. Blainey further stated, re its divisiveness, 'So long as the black armband view is influential; so long as it insists that the treatment of Aborigines was so disgraceful that no reparations might be adequate...and that black racism is justified, then Australia's future as a legitimate nation is in doubt.'

Social commentators such as Andrew Bolt have explicitly rejected the existence of Indigenous stolen generations and thus any supposed attempt by mainstream Australia to commit genocide. Like Blainey, Bolt also views criticisms of Australia's colonial past as divisive. He has condemned such attitudes as presented by the ABC, claiming they are, 'a paean of praise for what's actually a dysfunctional Aboriginal culture, a heaping of blame on non-Aboriginal society and a promotion of racial division and even a form of apartheid.'

Bolt has further argued, regarding claims of 'stolen generations, 'White children are robbed of their history, and black children of faith in the only society that can help them. White children are told lies, and black ones are fed...hopeless resentment...'

Bolt further maintains that attempts to compensate Indigenous Australians for their supposed historical mistreatment by white Australians will create a power imbalance and encourage Australia to split into battling racially-based enclaves. Bolt states, 'When one "race" of Australians gets handed more power over the rest [here Bolt is referring to "compensated" Indigenous Australians] , other Australians will identify with their own "race" or ethnicity, to defend their interests. Such race politics is a highway to hell, just when this fractured country needs to limp back to unity instead.'

Thus Bolt claims that mainstream Australia is left with a legacy of resentment while Indigenous Australia is left with the potential for revolt. Paraphrasing the warnings of Indigenous activist Professor Mike Dodson, Bolt states, 'Simmering anger in indigenous Australia over a failure to make good for past wrongs could easily turn into organised armed resistance.'

Thus Bolt claims that mainstream Australia is left with a legacy of resentment while Indigenous Australia is left with the potential for revolt. Paraphrasing the warnings of Indigenous activist Professor Mike Dodson, Bolt states, 'Simmering anger in indigenous Australia over a failure to make good for past wrongs could easily turn into organised armed resistance.'

Former Prime Minister, John Howard, has also rejected describing Australia as guilty of genocide and has further claimed that such claims, together with any national apology or development of a treaty with Indigenous Australians would serve to fracture the nation.

He has stated, 'I'm appalled at talk about treaty, that will be so divisive and will fail... The Australian public will not be attracted to the idea of a country trying to make a treaty with itself. I have said publicly as far back as 2007, I would support a change that recognises an historical truth that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were here before anybody else...Nobody can argue with that. But once it goes beyond that I think you find that opens up all sorts of other things.'

He has stated, 'I'm appalled at talk about treaty, that will be so divisive and will fail... The Australian public will not be attracted to the idea of a country trying to make a treaty with itself. I have said publicly as far back as 2007, I would support a change that recognises an historical truth that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were here before anybody else...Nobody can argue with that. But once it goes beyond that I think you find that opens up all sorts of other things.'  Here Howard appears to be arguing against constructions of Australia's history that would encourage guilt or shame among mainstream Australians and a sense of alienation among those of Indigenous ancestry.

Here Howard appears to be arguing against constructions of Australia's history that would encourage guilt or shame among mainstream Australians and a sense of alienation among those of Indigenous ancestry.When delivering the 1996 Sir Robert Menzies speech, Howard declared that Australia should not foster guilt and division and that its history was one of which it should be proud. He stated, 'This "black armband" view of our past reflects a belief that most Australian history since 1788 has been little more than a disgraceful story of imperialism, exploitation,

racism, sexism and other forms of discrimination. I take a very different view. I believe that the balance sheet of our history is one of heroic achievement and that we have achieved much more as a nation of which we can be proud than of which we should be ashamed.'

Howard further concluded, 'We need to acknowledge as a nation the realities of what European settlement has meant for the first Australians, the Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders, and in particular the assault on their traditions and the physical abuse they endured... But in understanding these realities our priority should not be to apportion blame and guilt for historic wrongs but to commit to a practical program of action that will

remove the enduring legacies of disadvantage.

That is why our priority should be a process of reconciliation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians built on a practical program to alleviate their disadvantage in terms of health, literacy, housing, employment and respect for their culture and traditions, as well as to facilitate the goal of greater economic independence.'

4. Condemning previous child-relocation policies as 'genocide' makes it more difficult to address current Indigenous child protection issues

There are those who argue that rejection of previous policies which created the supposedly 'stolen generations' as genocide has created major contemporary problems. They claim that this exaggerated condemnation of the manner in which Indigenous children were separated from their families in the past has meant that Indigenous children of today are left in hazardous situations. These critics claim that child welfare workers are so afraid of being accused of perpetuating the policies of the past that they leave children in hazardous home environments.

In an opinion piece published on May 13, 2016, in The Herald Sun, commentator Andrew Bolt stated, 'The "stolen generations" myth has made us leave Aboriginal children to be bashed, raped and killed. In fact, it's hurt more children than were ever proved stolen just for being Aboriginal.'

Bolt quotes the indigenous Chief Minister of the Northern Territory, Adam Giles, who claims, 'You mean to tell me when we've got all these alleged cases of chronic child sexual abuse, children running around on petrol, going on the streets at night sexualising themselves in some circumstances, and there's only one permanent adoption, for fear of Stolen Generation? That is not standing up for kids.'

Bolt presents a number of instances from the Northern Territory where he claims children were left with inappropriate family carers because welfare officers were afraid they would be accused of creating further stolen generations. Bolt presented one case in which he claimed, 'In 2003, five-month-old Mundine Orcher died in Brewarrina after what the coroner called a "systematic attack" while in the care of relatives - and a day after a Department of Community Services (DoCS) officer dropped off a fridge and washing machine.' In this case, Bolt claims, welfare workers had been warned against removing the child. Bolt states, 'A DoCS report had advised that the "indigenous community needs to be treated, in child protection terms, with constant sensitivity to the historical impact of ... the stolen generations".'

Bolt claims to see a pattern of administrative neglect motivated by fear of repeating the so-called wrongs of the past in other Australian states. Bolt observes, 'The New South Wales Child Death Review Team found this same fear of removing Aboriginal children from danger. It investigated why Aboriginal children of drug addicts were 10 times more likely to die under the noses of welfare officers than were children of white addicts and blamed the "stolen generations".'

Bolt quotes the New South Wales review which concluded, 'A history of inappropriate intervention with Aboriginal families should not lead now to an equally inappropriate lack of intervention for Aboriginal children at serious risk.'

Two years later, on February 13, 2018, Bolt noted that though high numbers of Indigenous children were being removed from the families in order to protect them from mistreatment too many children were still being allowed to remain at risk. Bolt claimed, 'The evidence is that despite the high rate of removal we still save not too many Aboriginal children but too few. The "stolen generations" myth is making officials too scared to save children from danger, and some children are paying for this ideological nonsense with their lives.'

Bolt has been particularly critical of the ABC for, he claims, exaggerating the supposed 'stolen generations' story and by so doing encouraging both governments and welfare agencies to leave Indigenous children at risk. He queried, 'When will the ABC put the lives of Aboriginal children above their "stolen generations" myth? What is more important to them?'

5. Addressing current Indigenous issues is more important than acknowledging supposed past mistreatment

Opponents of recognising Indigenous genocide often argue that this preoccupation with the past has no practical value. They claim that it is part of a suite of issues that have only 'symbolic' value. These issues include an Indigenous treaty, Indigenous inclusion in the Constitution, changing the date of Australia Day, changing the words of the national anthem and an apology to members of the Stolen Generations. All these issues (of which only one has currently been acted on) are claimed to have no real worth, that is, they are said to do nothing to address the real-world contemporary problems of Indigenous Australians.

This point has been made repeatedly by former prime minister John Howard, both when he was in office and since.

In 1997, following the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families which judged that these separations were genocide, Howard and the government he led decided that a national apology was not called for. The Prime Minister stated, 'Although in a personal sense many Australians will feel sorrow and regret in relation to past injustices suffered by sections of the Australian community, it is the view of my government that a formal national apology, of the type sought by others, is not appropriate.' Instead, the Prime Minister declared that his government believed it was important to address Indigenous disadvantage in areas of health, housing and education.

In the same year, at the Reconciliation Convention in Melbourne, Howard declared, 'Reconciliation will not work if it puts a higher value on symbolic gestures and

overblown promises rather than the practical needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander people in areas like health, housing, education and employment...we should...focus our energies on addressing the root causes of current and future disadvantage among our indigenous people.'

The day after Howard made these comments at the Melbourne Reconciliation Convention, he expanded them in Parliament, stating, '[We] believe that the essence of reconciliation lies not in symbolic gestures... It is important on these issues that the parliament, as far as possible, speak with one voice-not in overblown rhetoric but in a practical determination to address the areas of disadvantage that indigenous people suffer...We are not obsessed with symbolism. We are concerned, though, with practical outcomes.'

The Prime Minister reiterated these points in 2000, stating, 'National reconciliation calls for more than recognition of the damaging impact on people's lives of the mistaken practices of the past. It also calls for a clear focus on the future. It calls for practical policy-making that effectively addresses current indigenous disadvantage particularly in areas such as employment, health, education and housing.'

Though this comment suggests recognition of past injuries and the need for present 'practical' progress could go hand in hand, subsequent comments from the prime minister demonstrated that the practical emphasis superseded and ultimately replaced the 'symbolic' gestures. Howard later stated, 'I do not hold the view that symbolism is irrelevant in public life, although... Anybody who imagines that resolutions and symbolism are a substitute for effective working policies...is deluding himself.'

Though this comment suggests recognition of past injuries and the need for present 'practical' progress could go hand in hand, subsequent comments from the prime minister demonstrated that the practical emphasis superseded and ultimately replaced the 'symbolic' gestures. Howard later stated, 'I do not hold the view that symbolism is irrelevant in public life, although... Anybody who imagines that resolutions and symbolism are a substitute for effective working policies...is deluding himself.'  Here the prime minister appears to be making the same point as many others who discount the value of 'symbolic' actions, that is, that a government can only proceed with one or the other.

Here the prime minister appears to be making the same point as many others who discount the value of 'symbolic' actions, that is, that a government can only proceed with one or the other.The Prime Minister made essentially this point four years later, in 2004, at the launch of the 'Trust' Exhibition Australian Prospectors and Miners Hall of Fame in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia. Howard declared, 'All the theories in the world will not replace the value of employment; will not replace the value of sustainable economic opportunities; and will not replace the value of the embracement of the Indigenous people as part of our economic future. And that is why my government has placed such a great emphasis on what I call practical reconciliation, on giving all of the people of this country, irrespective of their background or their heritage, economic opportunity. And the greatest measure of that, of course, is to give people employment.'

This emphasis on 'practical reconciliation', rather than on aspects of reconciliation that are dismissed as 'theories' or 'symbolic reconciliation', encourages critics to minimise or dismiss claims of genocide such as those made by the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families.