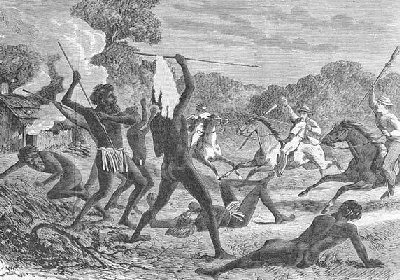

Right: The Myall Creek massacre has been generally acknowledged and was documented in magazines and newspapers of the period, including by contemporary illustrations.

Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Arguments in favour of recognising the treatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as genocide

Arguments in favour of recognising the treatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as genocide

1. Indigenous genocide was the intent of actions and policies of many white settlers and administrators

There are many who maintain that the large-scale deaths of Indigenous Australians with the advent of white settlement was frequently the result of deliberate actions on the part of settlers and administrators and the governments for which they acted. These historians and commentators argue that white settlement of Australia was accompanied by an attempt on the part of many white settlers and administrators to quell the Indigenous population, up to and including by complete annihilation, and that this was a deliberate policy which was a form of genocide. It has further been claimed that later policies which disrupted Indigenous communities and took their children from them was part of another deliberate policy, this time to allow these ethnic groups to fade out of existence.

It has been repeatedly claimed that many settlers both wanted and attempted to achieve the complete destruction of Indigenous populations. Professor Dirk Moses, while noting that the term 'genocide' had yet to be coined in early post-settlement Australia, has claimed that many settlers were seeking just that in relation to Australia's indigenous population. Moses has stated, 'When settlers called for the extermination of indigenous peoples - and they often did - they were advocating genocide - the destruction of a people- particularly if we view the Australian Aborigines as comprising many locally based peoples rather than a single nation.'

Similarly, it has been claimed that some governors and other administrators appeared willing to bring about the extermination of Indigenous peoples. Historian John Harris, in a treatment of three disputed Indigenous massacres, two in Western Australia and one in New South Wales, comments on the actions and attitudes of the first Western Australian Governor and the founder of the Swan River settlement, Captain James Stirling.

Harris has observed that following the killing of some male members of the Murray River tribe at Pinjarra (variously estimated at from 20 to 80 in number

near Perth, in 1834, in an incursion led by Stirling, the governor noted in his official report to the Colonial Office in London that he had set out to punish the whole tribe and thus break their resistance. The extent to which this endeavor might go was indicated by the warning Stirling gave the survivors of the tribe, which was reported in The Perth Gazette at the time. Stirling threatened that if there were further trouble, 'four times the present number of men [government forces] would proceed amongst them [the Murray River people] and destroy every man, woman and child.'

near Perth, in 1834, in an incursion led by Stirling, the governor noted in his official report to the Colonial Office in London that he had set out to punish the whole tribe and thus break their resistance. The extent to which this endeavor might go was indicated by the warning Stirling gave the survivors of the tribe, which was reported in The Perth Gazette at the time. Stirling threatened that if there were further trouble, 'four times the present number of men [government forces] would proceed amongst them [the Murray River people] and destroy every man, woman and child.'

In Tasmania, policies which ultimately resulted in the deaths of all full-blood Tasmanian Indigenes became progressively more severe. Bounties that were initially introduced at œ5 for an adult Aboriginal person and œ2 per child to encourage colonists to bring in live captives were later extended to cover not only the living but also the dead. Ultimately, a couple of thousand soldiers, settlers and convicts were recruited for a general movement against Aboriginal people in late 1830. During this major campaign, Governor Arthur rode his horse up and down the lines. He personally oversaw the operation. He sent dedicated skirmishing parties out in front of 'the line'. Surviving records do not reveal how many casualties may have resulted.

Statements and actions such as Stirling's and Arthur's have been condemned as genocidal.

It has also been claimed that Australian state and federal policies which involved the resettlement of indigenous populations and particularly the placement of Indigenous children in households or institutions run by white Australians were a deliberate attempt to destroy racial identity and the race itself.

In 1937, at the Canberra Conference on Aboriginal Welfare, the Western Australian Chief Protector of Aborigines, Octavius Neville, advanced a program of interbreeding that would see the disappearance of Indigenous peoples. He declared, 'Are we going to have a population of 1,000,000 blacks in the Commonwealth, or are we going to merge them into our white community and eventually forget that there ever were any aborigines in Australia?'

Propositions such as these have since been condemned as openly genocidal.

Propositions such as these have since been condemned as openly genocidal.Following Australia's signing of the United Nations Genocide Convention, there appeared to be an overt recognition by Australian governments that the country's long-established practice of removing Indigenous children from their families was genocide. An exchange of letters between the Commonwealth and Northern Territory governments in 1949-1950, shows both governments acknowledging that child removal policies probably contravened the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Genocide Convention.

On May 26, 1995, the report of the 'Bringing Them Home: National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families' was tabled in the Australian Federal Parliament. The Inquiry's report acknowledged that 'Indigenous children have been forcibly removed from their families and communities since the very first days of the European occupation of Australia.' Children removed from the families in this way have come to be termed 'The Stolen Generations'

The Inquiry further judged, 'The Indigenous families and communities have endured gross violations of their human rights. These violations continue to affect indigenous people's daily lives. They were an act of genocide, aimed at wiping out indigenous families, communities, and cultures, vital to the precious and inalienable heritage of Australia.'

The Inquiry found that 'the predominant aim of Indigenous child removals was the absorption or assimilation of the children into the wider, non-Indigenous, community so that their unique cultural values and ethnic identities would disappear, giving way to models of Western culture. In other words, the objective was `the disintegration of the political and social institutions of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economical existence of' Indigenous peoples... Removal of children with this objective in mind is genocidal because it aims to destroy the "cultural unit".'

2. Indigenous people died in very large numbers because of white settlement

Those who argue that an Indigenous genocide occurred in Australia tend to emphasise the great number of Indigenous lives that were lost consequential to white settlement. For some of these commentators, population decline of this scale, resulting from the effect of one group of people upon another, should be referred to as genocide.

In an article published in Aboriginal History in 2003, historian John Harris noted, 'The awful but surely undeniable fact of Aboriginal history, the one fact which transcends all other facts and all other estimates, reconstructions, analyses, guesses, misrepresentations, truths, half-truths and lies, is the fact of the immense and appalling reduction in the Aboriginal population during the first 150 years of European settlement.'

Harris first identifies the estimates of the Indigenous Australian population at the time of white settlers' arrival, noting the conservative nature of these figures. 'Estimates of Australia's Aboriginal population in 1788 range from 300,000 to well over one million. The lower estimate, proposed by the English anthropologist Arthur Radcliffe-Brown, used to be generally accepted but many now regard it as far too low. Based on census statistics and reports gathered several decades after European settlements, it failed to take into account the rapid decline in Aboriginal numbers within the first 10 years of the arrival of European settlers anywhere in Australia.'

Harris then gives figures showing the numerical decline in the Australian Indigenous population that followed upon white settlement. Harris notes, 'By the 1920s, census figures indicate that only about 58,000 'full-blood' Aboriginal people survived in Australia.'

Using the conservative estimate of an initial Indigenous population of 300,000, 132 years later the number had dropped by more than five hundred percent.

Using the conservative estimate of an initial Indigenous population of 300,000, 132 years later the number had dropped by more than five hundred percent. Harris further argues that the extent of the loss of life is more important than the various methods by which it was brought about. For him it is the fact of these deaths rather than whether they occurred violently that is significant. He states, 'The tragically huge depopulation of Aboriginal Australia, by whatever means, is far more important an issue than arguments about how the victims actually died. More Aboriginal people died of venereal diseases, hunger, and smallpox than by violence. But the debate about the extent of violent death has lately assumed considerable significance and become a kind of battle for how history is interpreted.'

For Harris and other similarly minded historians, depopulation is the central factor, rather than whether it occurred as a result of disease and relocation or massacres and frontier wars.

For Harris and other similarly minded historians, depopulation is the central factor, rather than whether it occurred as a result of disease and relocation or massacres and frontier wars.It has also been argued that settler groups should be seen as at least partially complicit in all non-violent causes of large-scale Indigenous death after white colonisation. Christopher Warren, an Australian journalist and writer, has argued in favour of the disputed claim that the First Fleet deliberately infected local Indigenous populations with a smallpox, which resulted in large scale deaths.

However the disease was first brought to Australia, smallpox spread across the country with the advance of European settlement, bringing with it shocking death rates. The disease affected entire generations of the Indigenous population and survivors were in many cases left without family or community leaders. The spread of smallpox was followed by influenza, measles, tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases, to all of which Australia's Indigenous peoples had no resistance, and all of which brought widespread death.

However the disease was first brought to Australia, smallpox spread across the country with the advance of European settlement, bringing with it shocking death rates. The disease affected entire generations of the Indigenous population and survivors were in many cases left without family or community leaders. The spread of smallpox was followed by influenza, measles, tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases, to all of which Australia's Indigenous peoples had no resistance, and all of which brought widespread death.

Some historians have contended that white colonisers can be held in part responsible for most post-settlement events which caused widespread Indigenous deaths. Historian Tony Barta has cited historian Raymond Evans who claims with regard to Indigenous deaths through disease, 'A degree of human agency is always involved in the spread, control and treatment of diseases, and explicit acts of commission and omission, as well as accident and fate' need to be considered 'before violence and disease are pigeonholed neatly as mutually exclusive causes of annihilation - the one intentional, the other accidental.'

A research piece published in The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health in 2011 serves to demonstrate the level of responsibility white colonialists could be considered to have for the spread of a disease such as tuberculosis among Indigenous Australians. The authors note, 'It is generally agreed that there was no TB in Australia before European settlement, and that Mycobacterium tuberculosis was introduced by the First Fleet in 1788. In the second half of the 19th century tuberculosis became the major cause of death in Aboriginal communities in the southern parts of the country, mainly as a result of the changing way of life of many of these communities. From a nomadic lifestyle they were increasingly forced to live in established settlements, where they suffered from overcrowding, unhygienic conditions, poor nutrition and considerable psychological stress.'

This study argues that white colonisers did more than introduce the disease; they forcibly imposed the living conditions that allowed it to spread. The spread of other diseases, such as venereal diseases and influenza, not known to Australia prior to white colonisation, has similarly been attributed to lifestyle changes and other exigencies forced upon Indigenous populations after colonisation.

This study argues that white colonisers did more than introduce the disease; they forcibly imposed the living conditions that allowed it to spread. The spread of other diseases, such as venereal diseases and influenza, not known to Australia prior to white colonisation, has similarly been attributed to lifestyle changes and other exigencies forced upon Indigenous populations after colonisation.

3. National truth-telling can be positively managed so as not to provoke guilt or hostility among mainstream Australians

Those who support a process whereby mainstream Australia officially acknowledges the painful and often violent nature of its historical interactions with Indigenous Australians claim that such 'truth-telling' can be managed positively in a way that does not foster anger, resentment and guilt.

The model suggested is based on principles informing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a restorative justice body assembled in South Africa after the end of apartheid.

Canada has had a long-running Truth and Reconciliation Commission (which was active from 2008 to 2018).

Canada has had a long-running Truth and Reconciliation Commission (which was active from 2008 to 2018).

Karen Mundine, a Bundjalung woman from northern New South Wales and head of Reconciliation Australia, together with Richard Weston, a descendant of the Meriam people of the Torres Strait, and head of the Healing Foundation, have argued, 'The focus should now turn to how we realise truth telling in this country, in a way that is safe for all involved... Truth telling can and should advance reconciliation, provide healing to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and liberate Australians from the shadow of an unhelpful focus on shame and guilt. To do so, the approach must be reciprocal, collaborative and respectful.'

In 2018 Reconciliation Australia and the Healing Foundation hosted a truth-telling symposium that explored the reasons for such a process and what it might look like. The symposium heard that truth telling might include official apologies, truth and reconciliation commissions, memorials, museums, revision of education content, and healing centres.

Mundine and Weston have stated, 'Truth telling is not about engendering guilt or shame in non-Indigenous Australians but about addressing past injustices and serving as an "end-point to a history of wrongdoing", allowing relationships to start anew...

For their part, non-Indigenous Australians must bear witness to the experiences, sufferings and survival of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, embrace the truths that are shared and work with us towards resolving outstanding injustices.

If we can achieve this vision for a reciprocal, collaborative and respectful process of truth telling, we will come closer to realising reconciliation and healing.'

In May 2017, around 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander delegates gathered at Uluru to hold an historic First Nations Convention, resulting in the Statement from the Heart. The Statement was informed by regional dialogues conducted by the Referendum Council with more than 1,200 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander delegates nationwide. It called for a Makarrata Commission to supervise agreement-making (treaties) between government and First Nations' Peoples and facilitate a process of local and regional truth-telling.

On October 9, 2018, Reconciliation Australia and The Healing Foundation brought together experts from around the country to develop a set of guiding principles to progress truth-telling in Australia. Those who promote this truth-telling process maintain that it is intended to develop understanding on the part of mainstream Australia, not guilt or hostility.

4. Acknowledging genocide directed against Indigenous people in the past will assist Indigenous people dealing with present issues

Those who favour acknowledging Indigenous genocide as part of historical truth telling argue that this will be of benefit to contemporary Indigenous Australians struggling with a range of social and psychological issues.

These advocates claim that the burden of violent dispossession, cultural disruption and family dislocation (all forms of genocide) create transgenerational trauma which continues to affect Indigenous Australians to this day prompting depression, drug dependence, alcoholism, family disfunction and suicide. They further claim that formal recognition of the impacts of past wrongs would assist Indigenous people come to terms with their feelings of alienation and the maladaptive behaviour that results.

Richard Weston, the head of the Healing Foundation has claimed that truth telling is about the past, the present and the future. He has stated, 'The trauma we face in our day-to-day lives, either directly or indirectly, has its genesis in the violent early history of Australia's Frontier Wars and the genocidal policies that followed, including the forced removal of children.'

The Healing Foundation's Internet site explains, 'If people don't have the opportunity to heal from past trauma, they may unknowingly pass it on to others. Their children may experience difficulties with attachment, disconnection from their extended families and culture and high levels of stress from family and community members who are dealing with the impacts of trauma.'

Advocates claim this trauma is generations deep among Indigenous Australians and has still to be fully acknowledged by mainstream Australians or by many Indigenous people themselves which makes dealing with its legacy very difficult.

Advocates claim this trauma is generations deep among Indigenous Australians and has still to be fully acknowledged by mainstream Australians or by many Indigenous people themselves which makes dealing with its legacy very difficult.A recent report from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 'Children living in households with members of the Stolen Generations', attempts to quantify the effect of this trauma transmitted from one generation to another. The report notes that children who are under 15 and living in a household with a member of the Stolen Generations are having poorer life outcomes than other children.

Richard Weston explains, 'We think it's important people understand the truth around the Stolen Generations: that people were removed from their families so culture wouldn't be transmitted, to change Aboriginal people and make them become more assimilated...

And now we have wide-spread issues in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities that are really hard to solve, around child neglect, child abuse, drug and alcohol issues. There's a cocktail of dysfunction in our communities which is a direct result of past policies.

We need to understand the truth of that story so we can create solutions today that are better-informed and based on evidence and are going to make a difference for people.

For our people, for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Stolen Generations and their children and their descendants, the importance of truth is about diagnosing the problem correctly and then finding the correct solution.'

5. A refusal to acknowledge Australian genocide has prevented Australia outlawing domestic genocide and prompted it to ignore the crime internationally

Critics of the Australian government's failure to designate the mistreatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as genocide argue that this stands in the way of Australia enacting legislation prohibiting genocide within Australia. They similarly argue that Australia's historical blindness to the country's own acts of genocide may make it more reluctant to condemn acts of genocide committed in other jurisdictions.

Despite being one of the first States to sign the United Nations Genocide Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide in 1949, Australia has drafted no domestic legislation outlawing genocide within this country. This is a follow-up action urged by the Convention.

Critics have suggested that the mindset which has allowed Australia to deny historical genocide committed by governments and individuals within its own borders may account for its failure legally to prohibit such actions.

Critics have suggested that the mindset which has allowed Australia to deny historical genocide committed by governments and individuals within its own borders may account for its failure legally to prohibit such actions. Professor Ben Saul, Challis Chair of International Law at the University of Sydney, has condemned Australia's failure to formulate laws prohibiting genocide within this country. In an article published by the Sydney Law Review in December 2000, Professor Saul has stated, 'While the promulgation of laws alone is not sufficient to prevent genocide, law is nevertheless a fundamental aspect of prevention.'

Professor Saul has linked this failure to enact laws prohibiting genocide within Australia with Australia's refusal to acknowledge genocidal crimes committed by its own citizens against the country's Indigenous peoples. Professor Saul has stated, in the article published in 2000, 'Australia has been complacent about prohibiting genocide for over 50 years now and has arguably committed genocide against its own indigenous people during that time.' Saul suggests Australia is afraid to confront the crimes committed in the past and that this fear prevents it acting in the present. Professor Saul commented, 'Australians will know soon enough whether [their] Government is still too afraid of the dark child ghosts from the past who are haunting the present.'

It has further been suggested that Australia's refusal to admit to its own acts of historical genocide has bred a blindness or an insensitivity which explains its reluctance to condemn genocide committed in other parts of the world.

Colin Tatz, Visiting Professor in Politics and International Relations at ANU and the founding director of the Australian Institute for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, has condemned Australia for unjustifiable complacency regarding crimes of genocide in its own history. Professor Tatz has cited political figures from the late 1940s who indicated this sense of moral superiority at the time Australia became a signatory to the United Nations Genocide Convention. One is quoted as stating, 'The horrible crime of genocide is unthinkable in Australia ... That we detest all forms of genocide ... arises from the fact that we are a moral people.'

Professor Tatz went on to challenge Australia's response to several atrocities which international opinion has regarded as genocide but about which Australia has remained relatively silent. Tatz focuses on Australia's timid response to events that occurred in Turkey between 1915 and 1923 - including the deaths of 1.5 million Armenians, between 750,000 and 900,000 Greeks and between 275,000 and 400,000 Christian Assyrians.

Tatz notes the far stronger response taken by many other nations, observing that by the centenary anniversary in April 2015, twenty-three nation-states (including former Turkish allies Germany and Austria) had officially recognised the genocide, as had forty-three of fifty American state governments, and two of Australia's six state parliaments. Recognition has also come from the European Parliament, the Council of Europe, the World Council of Churches, Pope Francis, and the International Association of Genocide Scholars. Some countries have criminalised denial of the event.

Tatz contrasts this with what he claims is Australia's inadequate response. Tatz observes that in February 2015 the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) declared Australia's sympathy for 'the horrific and tragic loss of life and suffering' that occurred as a result of Turkey's actions against Armenia. 'There is no question that these events (which included massacres and forced marches) took place' but the 'government does not recognise these events as "genocide"'.

Tatz argues that Australia's definition of genocide is problematic, allowing it to ignore both crimes committed by its own citizens within its own borders and those committed elsewhere by other nations.