Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Further implications

Further implications

Any discussion of Indigenous genocide must begin with an act of cultural empathy on the part of mainstream Australia. It is easy for an imported culture, which has acquired a position of almost absolute dominance, to minimise or ignore the Indigenous culture and the loss it has endured. As the federal Minister for Indigenous Australians, Ken Wyatt, an Indigenous man himself, has stated, 'History is generally written from a dominant society's point of view and not that of the suppressed...therefore true history is brushed aside, masked, dismissed or destroyed.' Without mainstream Australia attempting to register factually and emotionally the position of Indigenous Australia no further discussion can be had.

From an Indigenous perspective, any discussion of genocide must begin with a consideration of the impact of European settlement on Indigenous culture, social groups and physical survival. Judged by any of these measures, the impact has been dire - resulting in loss of culture, disruption of social groups and enormous loss of life.

The precise methods by which this disruption and loss occurred is not the primary issue. Discussing genocide generally in the aftermath of World War II, Winston Churchill argued that the term was 'never meant to pertain exclusively to direct killing, this being but one means to the end of destroying the identity of a targeted group.'

Churchill also had reservations about requiring that genocide only occurred where there was 'demonstrable intent', arguing this 'established a requirement that would be virtually impossible ever to prove.'

Churchill also had reservations about requiring that genocide only occurred where there was 'demonstrable intent', arguing this 'established a requirement that would be virtually impossible ever to prove.'

From an Indigenous perspective, genocide has occurred when the effect of genocide results; that is, when culture, social groupings and population have either been lost or so undermined as to be extraordinarily imperilled. This is seen by many Indigenous Australians as a source of existential grief - what gave meaning has been destroyed. Intergenerational transmission of cultural trauma has had enduring effects upon many Indigenous Australians.

An overview of the historical situation and its consequences was given by Dr Michael Halloran, lecturer at La Trobe University School of Psychological Science in 2004. Dr Halloran stated, 'The experience of Aboriginal Australians since European settlement is replete with suppression of their cultural practices and knowledge by the dominant cultural group/s in Australia.

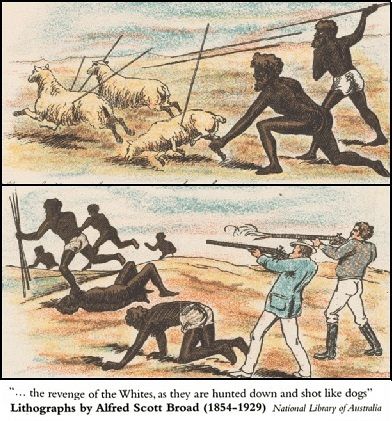

In the first century of settlement, these included land dispossession by force, theft of women, slavery and war, introduced diseases, and the missionary zeal for Aboriginal people to embrace Western religion and reject their own spiritual beliefs such as the dreaming. Moreover, settlement brought with it the assertion of British sovereignty and law, which effectively displaced indigenous customary law.

In the 20th century, further intervention into Aboriginal culture and life was evidenced in the Government's White Australia Policy and an explicit strategy of indigenous assimilation through forced removal of children from their family of origin and placement with Europeans. This latter strategy, referred to as the Stolen Generations, was perhaps the most critical assault on Aboriginal culture as it undermined and destabilized Aboriginal social structures central to cultural practice, and thus, transmission.

Contemporary events in Australia have also undermined attempts by Aboriginal people to address their cultural priorities and autonomous lifeways. These include legislative interference in the Native Title Act, equivocal support for the aims of Indigenous reconciliation and for the findings of the Stolen Generation report into the forced removal of children, and the recent dismantling of ATSIC. Significantly, the current government dismissed the cultural importance of ATSIC by claiming that it was 'too preoccupied with symbolic issues', as well as unambiguously adopting a policy of mainstreaming Aboriginal services...[T]hese strategies potentially undermine the pursuit of indigenous cultural autonomy and implicitly encourage a culture and cycle of dependency amongst Aboriginal Australians.

Although one might argue that there is no direct motive by the majority in Australia to encourage Aboriginal dependency, research shows that people prefer to offer dependency- rather than autonomy-based help to low-status outgroups to maintain social dominance and insure intergroup status-relations. Thus, dependency-based policies subtly discourage cultural independence and...can be seen to be motivated by the majority culture to maintain its superior status.

Altogether, the contemporary and historical interventions into Aboriginal life have been argued to represent a form of cultural genocide.'

Genuine recognition of attempted Indigenous genocide is challenging for mainstream Australia. It involves the recognition that Indigenous Australians are a group against whom a great wrong has been perpetrated, legally and morally. It redefines the relationship between mainstream and Indigenous Australians. It presents Australia as a continent which was taken not ceded.

A full and genuine recognition of Indigenous genocide would make issues such as whether Australia Day should be celebrated on January 26, or whether statues of Captain Cook should name him as the discoverer of Australia, or whether the lyrics of Australia's national anthem should be altered to remove 'young and free', far less contentious as it would truly regard the Indigenous perspective.

However, a full and genuine recognition of Indigenous genocide has more far-reaching implications for issues such as constitutional recognition, a treaty with Indigenous Australians, land rights, reparations and parliamentary representation. It is more than 'symbolic' because it involves questions of sovereignty and identity.

The recognition of genocide would involve mainstream Australia adopting a position of respect toward the descendants of the continent's Indigenous population and viewing them as the victims of a crime with whom an accommodation must be made. Currently, Australia, in common with many countries with a colonial past, has made only halting progress in this direction.