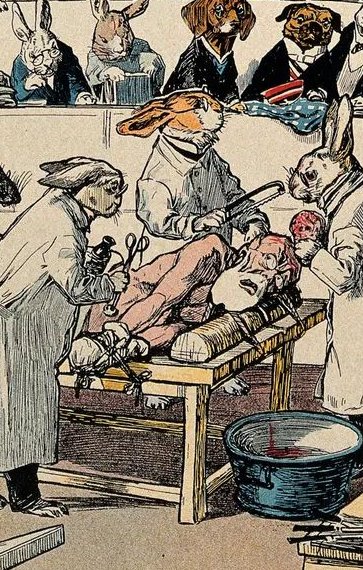

Right: Animals getting their own back. The ethics of using organs from living animals, once dismissed as a minor issue, has lately become a much-discussed subject.

Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Arguments in favour of using animal organs and tissues for human transplants

Arguments in favour of using animal organs and tissues for human transplants

1. Human organs for transplants are in too short supply

One of the primary arguments offered to support the use of animals to supply organs for human transplantation is that there are simply too few human organs available to meet the present need.

In the United States as of January 2019, there were over 113,000 people on the national waiting list in need of an organ. Every 10 minutes another person is added to the waiting list, and every day 20 people on the waiting list die before they can access the organ they need.

In the United Kingdom at the end of 2021, there was estimated to be 7,000 people on the transplant waiting list and over 470 people died while waiting for a transplant.

In the United Kingdom at the end of 2021, there was estimated to be 7,000 people on the transplant waiting list and over 470 people died while waiting for a transplant.  Germany had the highest number of patients waiting for a lung transplant in Europe in 2019 with 731 individuals on the waiting list during the year, while 45 died on the waiting list for a lung transplant. In Austria, five people requiring a lung transplant died during 2019.

Germany had the highest number of patients waiting for a lung transplant in Europe in 2019 with 731 individuals on the waiting list during the year, while 45 died on the waiting list for a lung transplant. In Austria, five people requiring a lung transplant died during 2019.  According to the statistics, the deceased organ donation rate in China currently is only about 0.6 per 1,000,000 China citizens, one of the lowest in the world. There are about 1 to 1.5 million people in China needing organ transplant every year and only 10,000 people can get a new organ successfully.

According to the statistics, the deceased organ donation rate in China currently is only about 0.6 per 1,000,000 China citizens, one of the lowest in the world. There are about 1 to 1.5 million people in China needing organ transplant every year and only 10,000 people can get a new organ successfully.  In 2019, 4419 Canadians were on a waiting list for a transplant. Of those, 77 percent were waiting for a kidney. Wait times can range from a few months to several years, during which time many would-be recipients die or become too ill to be given an organ.

In 2019, 4419 Canadians were on a waiting list for a transplant. Of those, 77 percent were waiting for a kidney. Wait times can range from a few months to several years, during which time many would-be recipients die or become too ill to be given an organ.

The picture is similar in Australia. In 2020, there were 1,270 organ transplant recipients from 463 deceased organ donors. As of 2021, more than 1,600 people are waiting for a life-saving transplant. There are also 12,000 people on dialysis, many of whom would benefit from a kidney transplant.

The pandemic has worsened the situation around the world for those waiting to receive a human organ. In the United Kingdom., 474 patients died by the end of 2021 while waiting for organs compared with 377 the year before. Most patients who died were waiting for kidney transplants. There were 3,391 transplants performed in 2020-2021 compared with 4,820 the previous year - a fall of 30 percent.  Those who argue for access to animal organs for transplants highlight figures like those above and note the vulnerability of organ transplant programs to complicating factors such as the current pandemic.

Those who argue for access to animal organs for transplants highlight figures like those above and note the vulnerability of organ transplant programs to complicating factors such as the current pandemic.

Many transplant specialists are enthusiastically awaiting the time when animal organs can be used to replace diseased or faulty human organs. Unlike human organs, where patients must wait for someone else to die, the supply of pig organs and cells would be virtually unlimited. Devin Eckhoff, a liver transplant surgeon at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Medical School, has said that if the procedure were approved, he could be producing 50 pigs for transplant within nine months. He has referred to the frustration of watching his patients become critically ill and then die waiting for replacement organs. He has stated, 'With organs available from pigs, think of how many more lives we could save.'

David Cooper, who co-directs the xenotransplantation program at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, has stated, 'It'll revolutionise medicine when it comes in. You'd have these organs available whenever you want them ... If somebody's had a heart attack, you could take their heart out and put a pig heart in on the spot. There is huge potential here.' David Cleveland, a heart surgeon at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, wants to use xenotransplantation to save babies born with congenital heart defects. Dr Cleveland has stated, 'At the moment, newborns can wait on the organ transplant list for more than three months for a new heart, often facing a mortality rate above 50 percent.'

2. Using animal organs and products has the potential to treat many serious human conditions

Those who support the use of animal organs and tissues to treat human diseases and other conditions argue that they can be used to address both life-threatening health issues and many others. Currently, human organs that can be donated after death include the heart, liver, kidneys, lungs, pancreas, small intestines, hands, face and uterus. Tissues include corneas, skin, middle ear veins, heart valves, tendons, ligaments, bones, and cartilage.  It has been argued that animal organs and tissues could be used to address all these needs.

It has been argued that animal organs and tissues could be used to address all these needs.

Researchers and transplant surgeons have pointed out the large number of organs that could be harvested from pigs to save human lives or treat non-life-threatening conditions. It is widely proposed that one day, genetically modified pigs could supply hearts, kidneys, lungs and livers to transplant centres to save patients from death.  Dylan Matthews, writing for Vox in an article published on October 23, 2021, stated, 'Genetically engineered pig hearts that could work for humans could dramatically extend lifespans for people with heart disease, and the same goes for lungs, liver, and other organs.'

Dylan Matthews, writing for Vox in an article published on October 23, 2021, stated, 'Genetically engineered pig hearts that could work for humans could dramatically extend lifespans for people with heart disease, and the same goes for lungs, liver, and other organs.'

Transplant-ready pigs could do more than just provide organs. Already, tissue taken from pigs is being used to treat human conditions. Pig heart valves have been used successfully for decades in humans. The blood thinner heparin is derived from pig intestines and Chinese surgeons have used pig corneas to restore sight.

It has also been suggested that pig tissues could be used to treat diabetes. Until the 1980s, humans with type I diabetes or insulin-dependent diabetes relied on animal insulin to control their blood glucose levels. Insulin is a hormone produced by the pancreas. People with type 1 diabetes make little to no insulin. This is because their immune system attacks this hormone. In 1921, Frederick Banting and his assistant Charles Best extracted insulin from dogs for the first time. In the years that followed, experts began extracting this hormone from the pancreas of pigs and cows. Currently, human-derived insulin is also available in the market.  It is hoped that soon, a transplantation from genetically modified pigs could remove the need for these patients to take insulin at all. These pigs could be used to produce the islet cells - clusters of hormone-producing pancreatic cells - needed by people with diabetes. A 2011 review in the medical journal The Lancet is optimistic that clinical xenotransplantation may soon become a reality, particularly for cellular grafts such as islets.

It is hoped that soon, a transplantation from genetically modified pigs could remove the need for these patients to take insulin at all. These pigs could be used to produce the islet cells - clusters of hormone-producing pancreatic cells - needed by people with diabetes. A 2011 review in the medical journal The Lancet is optimistic that clinical xenotransplantation may soon become a reality, particularly for cellular grafts such as islets.

Pig blood could also be used to give transfusions to trauma patients and people with chronic diseases like sickle cell anemia, who often develop antibodies against human blood cells because they have had so many transfusions. David Cooper, who co-directs the xenotransplantation program at UAB. the University of Alabama at Birmingham, has stated, 'Even dopamine-producing cells could be made by pigs, and transplanted into patients with Parkinson's disease.'

Jeremy Goverman, the principal investigator of Massachusetts general's skin trial, has explained how pig skin could also help burn patients. He often cannot find swatches of human skin big enough to cover large wounds. He believes a patch of skin from a pig would be more cost-effective than one from a cadaver. For countries that cannot maintain human tissue banks, pig skin might be a life-saving alternative. This is already being done in some places.  In October 2019, the united States Food and Drug Administration authorised human trials on the use of porcine (pig) skin tissue to treat human burns patients.

In October 2019, the united States Food and Drug Administration authorised human trials on the use of porcine (pig) skin tissue to treat human burns patients.

3. Experimental surgery is necessary, while guidelines, including informed patient consent, ensure it is ethical

It has been argued that all medical treatments applied to human beings were once experimental and that without patients being willing to undergo experimental treatments there would be no advances in medical practice. Supporters of the use of animal organs, tissues and cells to treat human beings stress that initial trials should only take place with the informed consent of patients and their families.

A range of international organisations have established guidelines and procedures describing how experimental medical treatments should take place. The World Health Organisation states, 'Clinical trials are a type of research that studies new tests and treatments and evaluates their effects on human health outcomes. People volunteer to take part in clinical trials to test medical interventions including drugs, cells and other biological products, surgical procedures, radiological procedures, devices, behavioural treatments and preventive care. Clinical trials are carefully designed, reviewed and completed, and need to be approved before they can start. People of all ages can take part in clinical trials, including children.'

The World Medical Association similarly states 'Medical progress is based on research that ultimately must include studies involving human subjects.' The Association further states, 'While the primary purpose of medical research is to generate new knowledge, this goal can never take precedence over the rights and interests of individual research subjects.' The Association also stresses the importance of the research subject having given his or her informed consent. Its guidelines state, 'Participation by individuals capable of giving informed consent as subjects in medical research must be voluntary. Although it may be appropriate to consult family members or community leaders, no individual capable of giving informed consent may be enrolled in a research study unless he or she freely agrees.' The guidelines further state, 'In medical research involving human subjects capable of giving informed consent, each potential subject must be adequately informed of the aims, methods, sources of funding, any possible conflicts of interest, institutional affiliations of the researcher, the anticipated benefits and potential risks of the study and the discomfort it may entail, post-study provisions and any other relevant aspects of the study. The potential subject must be informed of the right to refuse to participate in the study or to withdraw consent to participate at any time...' Where an individual cannot give informed consent, for example in the case of a minor, the guidelines state that the child's permission must also be received where he or she can express it The guideline state, 'When a potential research subject who is deemed incapable of giving informed consent is able to give assent to decisions about participation in research, the physician must seek that assent in addition to the consent of the legally authorised representative.'

A range of transplant surgeons and ethicists have explained the circumstances under which animal-to-human transplant surgery is ethical. Professor Julian Savulescu, Uehiro Chair in Practical Ethics at the University of Oxford, has stated, 'You can never know if the person is going to die catastrophically soon after the treatment - but you can't proceed without taking the risk. As long as the individual understands the full range of risks, I think people should be able to consent to these radical experiments.'

David Bennett, the 57-year-old patient who recently received a pig's heart at the University of Maryland Medical Center, stated before the surgery, 'It was either die or do this transplant.

I want to live. I know it's a shot in the dark, but it's my last choice.'  A spokesperson for the University of Maryland Medical Center stated after the surgery was performed, 'This patient came to us in dire need and a decision was made about his transplant eligibility based solely on his medical records. This patient made the extraordinary decision to undergo this groundbreaking surgery to not only potentially extend his own life but also for the future benefit of others.'

A spokesperson for the University of Maryland Medical Center stated after the surgery was performed, 'This patient came to us in dire need and a decision was made about his transplant eligibility based solely on his medical records. This patient made the extraordinary decision to undergo this groundbreaking surgery to not only potentially extend his own life but also for the future benefit of others.'

4. Organ rejection issues and the transmission of infections carried by the donor animal can be substantially overcome

Supporters of animal organs being used in human transplants argue that the major obstacles that formally prevented these transplants have been overcome. They claim that organ rejection and the transmissions of diseases carried by the donor animal have been virtually eliminated by new developments in gene technology.

It is claimed that the problem of organ or tissue rejection by the human recipient has been largely overcome. Modifications can now be made to the organs or tissues to be transplanted to cause the recipient's body to fail to recognise them as foreign. Researchers can now make targeted changes to the genes of the pig supplying an organ to remove markers that identify cells as foreign so the human immune system will not reject them.  In the case of David Bennett, the 57-year-old patient who recently received a pig's heart at the University of Maryland Medical Center, the Maryland surgeons used a heart from a pig that had undergone gene editing to remove a sugar in its cells that is responsible for the rapid organ rejection that would normally occur.

In the case of David Bennett, the 57-year-old patient who recently received a pig's heart at the University of Maryland Medical Center, the Maryland surgeons used a heart from a pig that had undergone gene editing to remove a sugar in its cells that is responsible for the rapid organ rejection that would normally occur.  The donated heart came from a pig developed by United States firm Revivicor. The animal had ten genes modified. Four of those were inactivated, including one that causes an aggressive immune response and one that would otherwise cause the pig's heart to continue growing after transplant into a human body. To further increase the chances of acceptance, the donor pig had six human genes inserted into its genome and Bennett is taking immune-suppressing medications.

The donated heart came from a pig developed by United States firm Revivicor. The animal had ten genes modified. Four of those were inactivated, including one that causes an aggressive immune response and one that would otherwise cause the pig's heart to continue growing after transplant into a human body. To further increase the chances of acceptance, the donor pig had six human genes inserted into its genome and Bennett is taking immune-suppressing medications.

Similar genetic technology has also been used to reduce the risk of porcine (pig) viruses being transmitted to the recipients of transplants and then to medical carers, family, friends, workmates, and others. Gene-editing technology can enable researchers to eliminate from the pig genome a group of viruses that some worry could jump to humans after a transplant. Porcine endogenous retroviruses (Pervs) are permanently embedded in the pig genome, and research has shown they can infect human cells, posing a potential hazard. Researchers in the United States have used the precision gene editing tool Crispr-Cas9 combined with gene repair technology to deactivate 100 percent of Pervs in a line of pig cells. These have been used to clone pigs that do not carry these retroviruses. Dr Luhan Yang, co-founder and chief scientific officer at the biotech company eGenesis, has stated, 'This research represents an important advance in addressing safety concerns about cross-species viral transmission.'  Dr Luhan further noted, 'Our work dispelled the shadow PERVs cast on the field more than a decade ago when the virus was discovered, while renewing our faith in xenotransplantation.'

Dr Luhan further noted, 'Our work dispelled the shadow PERVs cast on the field more than a decade ago when the virus was discovered, while renewing our faith in xenotransplantation.'  Professor Ian McConnell, from the University of Cambridge, has similarly stated, 'This work provides a promising first step in the development of genetic strategies for creating strains of pigs where the risk of transmission of retroviruses has been eliminated.'

Professor Ian McConnell, from the University of Cambridge, has similarly stated, 'This work provides a promising first step in the development of genetic strategies for creating strains of pigs where the risk of transmission of retroviruses has been eliminated.'

5. Using animal organs for transplants is ethically responsible

Those who support animal organs being used for human transplants argue that these transplants, especially when they involved domestic animals such as pigs, are ethically responsible.

One of the fundamental claims made by those who support animal organ transplantation is that human life is of greater value than animal life. Many ethicists maintain that human beings automatically privilege human life over animal life because of the greater intelligence and moral and emotional awareness of human beings. Juan Carlos Marvizon, a Professor of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) has presented a range of reasons as to why human life should be valued more highly than animal life. He has outlined in detail the aspects of human intelligence that place human beings in a higher category to all animals. He has also focused on the qualities of human emotion, stating, 'Mammals, birds and some other animals have a set of six basic emotions listed by Ekman: anger, fear, disgust, joy, sadness and surprise. However, we humans are able to feel many other emotions that regulate our social behavior and the way we view the world: guilt, shame, pride, honor, awe, interest, envy, nostalgia, hope, despair, contempt and many others. While emotions like love and loyalty may be present in mammals that live in hierarchical societies, emotions like guilt, shame and their counterparts pride and honor seem to be uniquely human.'  The greater intellectual, moral and emotional complexity of human beings is claimed by many to make their lives of greater worth than any animals. Proponents of animal transplants argue that this superiority of human beings justifies them in using human organs and tissues to extend their lives.

The greater intellectual, moral and emotional complexity of human beings is claimed by many to make their lives of greater worth than any animals. Proponents of animal transplants argue that this superiority of human beings justifies them in using human organs and tissues to extend their lives.

It is also claimed that the animals used to supply transplant organs or in experiments to develop successful transplant procedures are not subjected to unnecessarily cruel or painful treatment. Those who defend animal testing and the use of animals in medical procedures that help human beings note that most countries have protocols and regulations designed to reduce the amount of suffering these animals endure. On October 8, 2021, Justice published a discussion of the use of animals in medical treatments and scientific experiments. The piece was written by animal rights activist Grace Hussain who stated, 'Laboratories attempt to mitigate this suffering with the use of pain medications, sedation, and anesthesia. Another mitigation technique employed is that researchers set a limit to the level of suffering animal subjects will endure prior to euthanasia. Once an animal reaches the predetermined level of suffering the animals will be humanely euthanized.'

It is further argued that in using domestic animals such as pigs for transplants, animals such as apes and chimpanzees, which are endangered in their natural habits, are not having their species survival further put at risk. The Foundation of American Scientists has made a comparison between the use of primates and pigs to supply organs for human transplants. It suggests that the use of pigs raises fewer ethical concerns. It states, 'Although non-human primates such as chimpanzees are genetically closest to humans, reducing the chances of graft rejection, primates are endangered in the wild and their use as a source of replacement organs raises ethical concerns because of their high level of intelligence. As an alternative, some have proposed using pigs as a source of organs because they have large litters (up to 10 offspring) and a short gestation time (four months), are anatomically and physiologically similar to humans, are already produced as a food source, and provide some replacement tissues, such as heart valves.'