Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Further implications

Further implications

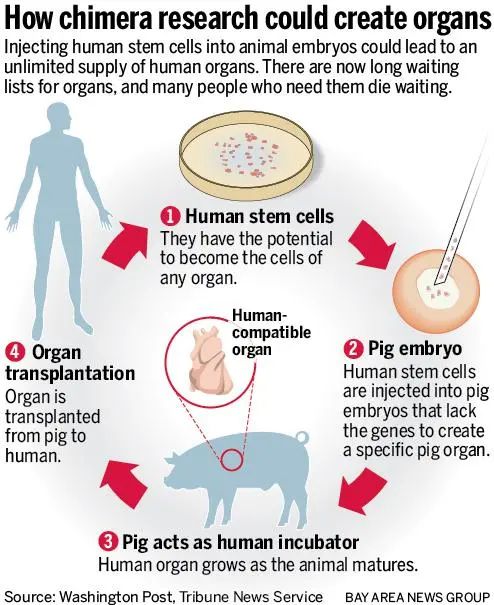

Currently, the transplantation into human recipients of organs taken from animals relies on gene-editing, manipulating the genes of the donor pig to remove certain qualities and adding human genes to create other qualities. These are the primary measures being used to prevent rejection of the transplanted organ and to help human recipients avoid certain diseases which pigs carry. Developments occurring now are taking these gene-editing processes much further. Key among these is the production of chimeras. A chimera is an animal carrying cells from two different species. In the context of transplantation, a chimera is an animal, such as a pig, which can be used to grow human organs.

Scientists are now working on a technique that would allow human organs to be grown inside pigs. For example, the DNA within a pig embryo that enables it to grow a pancreas is deleted, and human stem cells are injected into the embryo. These stem cells can develop into any type of cell within the body, and previous experiments using rats and mice suggest that they will automatically fill the gap created by the missing pancreas genes and form a pancreas that consists of predominantly genetically human cells.

It has been suggested that pigs could be used to grow many different types of transplant organ - kidneys, hearts, livers, and that these organs would have the particular advantage of being an exact match for the recipient patient as they will have been grown from that patient's own genetic material.

It has been suggested that pigs could be used to grow many different types of transplant organ - kidneys, hearts, livers, and that these organs would have the particular advantage of being an exact match for the recipient patient as they will have been grown from that patient's own genetic material. However, despite the obvious potential of such developments to revolutionise transplantation and save human lives many practical and ethical concerns have been raised. Critics are anxious about research projects involving the implantation of human brain stem cells into other animals or aiming at the creation of human-animal admixed embryos. There are concerns that in producing these chimeras, researchers may create animals which have properties that make them 'part human'. Megan Munsie, Deputy Director - Centre for Stem Cell Systems and Head of Engagements, Ethics & Policy Program, Stem Cells Australia, at the University of Melbourne, has noted, 'Human-animal chimeras blur the line about what it means to be human, and this raises serious ethical questions about how we should use them.'

Munsie goes on to suggest, 'Humans are widely (but not universally) thought to have a higher moral status than other animals. But human-animal chimeras blur this line. They are not fully human, nor fully non-human. So, the big question is whether (or under what conditions) we should be allowed to use them as a source of transplantable organs, in harmful research, or for other purposes we wouldn't use humans for.'

Munsie goes on to suggest, 'Humans are widely (but not universally) thought to have a higher moral status than other animals. But human-animal chimeras blur this line. They are not fully human, nor fully non-human. So, the big question is whether (or under what conditions) we should be allowed to use them as a source of transplantable organs, in harmful research, or for other purposes we wouldn't use humans for.'

Given the ethical dilemmas potentially raised by the creation of pig-human chimeras for organ transplantation, there are others who suggest that bioprinting may be a better source of transplantable organs which are compatible with the recipient and risk neither rejection nor infection. Bioprinting is an extension of traditional 3D printing. It can produce living tissue, bone, blood vessels and, potentially, whole organs for use in medical procedures, training, and testing. The cellular complexity of the living body has resulted in 3D bioprinting developing more slowly than mainstream 3D printing. However, bioprinting technology could provide the opportunity to generate patient-specific tissue for the development of accurate, targeted and completely personalised treatments. Despite its potential, there is still a long way to go before fully functioning and viable organs for human transplantation can be developed.

Both the breeding of chimera animals as organ sources and the creation of organs through bioprinting are extra-ordinarily expensive areas of research. If transplants of gene-edited organs, such as the heart recently received by David Bennett, prove to be successful, this area of research is likely to be preferenced over both chimeras and bioprinting as it is more developed and consequently less costly.