Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. Found a word you're not familiar with? Double-click that word to bring up a dictionary reference to it. The dictionary page includes an audio sound file with which to actually hear the word said. |

Background information

Background information

The full text of the extracted information below can be found at the Wikipedia entry titled Xenotransplantation. It can be accessed at

Animal to human organ or tissue transplants

Xenotransplantation (xenos- from the Greek meaning 'foreign' or strange), or heterologous transplant, is the transplantation of living cells, tissues or organs from one species to another. Such cells, tissues or organs are called xenografts or xenotransplants.

History

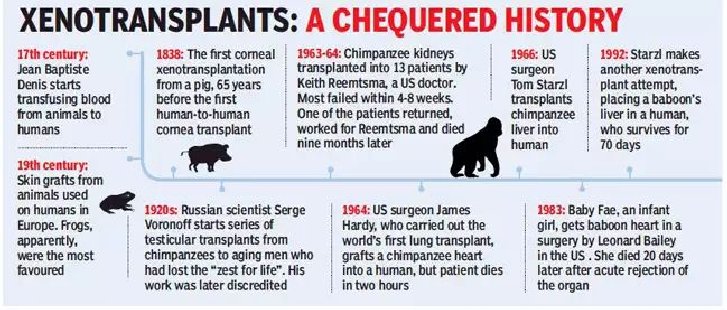

The first serious attempts at xenotransplantation (then called hetero-transplantation) appeared in scientific reports in 1905, when slices of rabbit kidney were transplanted into a child with chronic kidney disease. In the first two decades of the 20th century, reports of several subsequent efforts to use organs from lambs, pigs, and primates were published.

Scientific interest in xenotransplantation declined when the immunological basis of the organ rejection process was described. The next wave of studies on the topic came with the discovery of immunosuppressive drugs. Even more studies followed Dr. Joseph Murray's first successful renal transplantation in 1954 and scientists, facing the ethical questions of organ donation for the first time, accelerated their effort in looking for alternatives to human organs.

In 1963, doctors at Tulane University attempted chimpanzee-to-human renal transplantations in six people who were near death; after this and several subsequent unsuccessful attempts to use primates as organ donors and the development of a working cadaver organ procuring program, interest in xenotransplantation for kidney failure largely evaporated. Out of 13 such transplants performed by Keith Reemtsma, between 1963 and 1964, one kidney recipient lived for 9 months, returning to work as a schoolteacher. At autopsy, the chimpanzee kidneys appeared normal and showed no signs of acute or chronic rejection.

An American infant girl known as 'Baby Fae' with hypoplastic left heart syndrome was the first infant recipient of a xenotransplantation, when she received a baboon heart in 1984. The procedure was performed by Leonard Lee Bailey at Loma Linda University Medical Center in Loma Linda, California. Fae died 21 days later due to a humoral-based graft rejection thought to be caused mainly by an ABO blood type mismatch, considered unavoidable due to the rarity of type O baboons. The graft was meant to be temporary, but unfortunately a suitable allograft replacement could not be found in time.

Potential animal organ donors

Since they are the closest relatives to humans, non-human primates were first considered as a potential organ source for xenotransplantation to humans. Chimpanzees were originally considered the best option since their organs are of similar size, and they have good blood type compatibility with humans, which makes them potential candidates for xenotransfusions. However, since chimpanzees are listed as an endangered species, other potential donors were sought. Baboons are more readily available, but impractical as potential donors. Problems include their smaller body size, the infrequency of blood group O (the universal donor), their long gestation period, and their typically small number of offspring. In addition, a major problem with the use of nonhuman primates is the increased risk of disease transmission, since they are so closely related to humans.

Pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus) are currently thought to be the best candidates for organ donation. The risk of cross-species disease transmission is decreased because of their increased phylogenetic distance from humans. Pigs have relatively short gestation periods, large litters, and are easy to breed making them readily available. They are inexpensive and easy to maintain in pathogen-free facilities, and current gene editing tools are being adapted to pigs to combat rejection and potential zoonoses. Pig organs are anatomically comparable in size, and new infectious agents are less likely since they have been in close contact with humans through domestication for many generations. Treatments sourced from pigs have proven to be successful such as porcine-derived insulin for patients with diabetes mellitus.[30] Increasingly, genetically engineered pigs are becoming the norm, which raises moral qualms, but also increases the success rate of the transplant. Current experiments in xenotransplantation most often use pigs as the donor, and baboons as human models. In 2020 the United States Food and Drug Administration approved a genetic modification of pigs, so they do not produce alpha-gal sugars. Pig organs have been used for kidney and heart transplants into humans.

In the field of regenerative medicine, pancreatogenesis- or nephrogenesis-disabled pig embryos, unable to form a specific organ, allow experimentation toward the in vivo generation of functional organs from human stem cells in large animals. Such experiments provide the basis for potential future application of stem cell technology to generate transplantable human organs from the patient's own cells, using livestock animals, to increase quality of life for those with end-stage organ failure.